10 Highlights from Pace Gallery’s Virtual Saul Steinberg Exhibition

“The only real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes but in having new eyes,” said Marcel Proust, who famously penned his seven-volume modus operandi, “In Search of Lost Time,” during confinement to a bedroom due to asthma. Proust’s inspiration to visualize beyond concrete walls is currently a sentiment we, too, are collectively in search of, with our efforts to live, work, exercise, entertain, and dream within the limits of our own homes. Rediscovering the generosities of our stomping grounds at times serves a challenge, whether we breathe in a pocket-sized New York studio or sweep in ample square footage outside the urban domain.

Similar to Proust, artist Saul Steinberg was a homebody, creating a body of work—which exceeds 8,000 drawings—about the whimsy and potentials of life indoors. “Imagined Interiors,” a virtual exhibition on Pace Gallery’s Online Viewing Room, offers a visit to interiors Steinberg illustrated with a post-World War II humor, imagining the new order forming before him with a bitterly joyous and tirelessly curious pen. The urge to revisit Steinberg’s elating universe found the gallery’s associate curatorial director, Michaela Mohrmann, shortly after our realities shifted from leading lives facing outside to those spent indoors. “I realized there could not be a better time to re-introduce Steinberg’s whimsical take on the potentials of home,” she told Interior Design, and added that although he maintained a social circle in New York—where he lived in the Village and the Upper West Side—Steinberg chose to spend a considerable amount of time in isolation.

Born to Jewish parents in Romania in 1914, Steinberg first became familiar with paper at his father’s printing and bookbinding shop in Bucharest. Escalating anti-Semitism in the University of Bucharest, where he studied Philosophy, prompted him to enroll in the Regio Politecnico in Milan for an architecture degree in 1933. His cartoons in the Italian newspaper, Bertoldo, not only provided him financial means, but also made him a sought-after cartoonist. In 1940, the young Steinberg—after receiving his architectural degree and publishing his cartoons in American publications such as Harper’s Bazaar and LIFE—was forced to leave Europe due to the rise of fascist regime. He eventually settled in New York City in 1942 after first traveling through Dominican Republic and married his fellow Romanian artist, Hedda Sterne, two years later. Although Steinberg carved himself a reputation as a cartoonist for The New Yorker, he was also a prolific photographer, muralist, and painter who exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney American Museum of Art as well as with commercial gallerists, such as Betty Parsons and Sidney Janis.

Pace Gallery’s exhibition virtually walks visitors through Steinberg’s take on modern life in the mid-20th century America, during which the society experienced a crucial economic, social, and cultural revolution. His subjects—whether himself as a cat or an anonymous woman indulging in her drawing practice—are caught up in a sweet hassle of the mundane, from the comfort of their homes, while the world outside is in rapid transformation with buildings rising and cars passing in full speed. The artist’s search for creative stimulus while inside results in drawings he directly applied on architectural structures or humorous renditions of human and animal hybrids trapped in curious circumstances. As architectural characteristics surrounding Steinberg transform in accordance with growing wealth and technology in the society, he transfers his observations onto paper with a keen eye trained in architecture.

Play the exhibition’s audio offering of Charles Louis Ambroise Thomas’s “Gavotte” and scroll through highlights from “Imagined Interiors,” on view at Pace Gallery’s website through April 6.

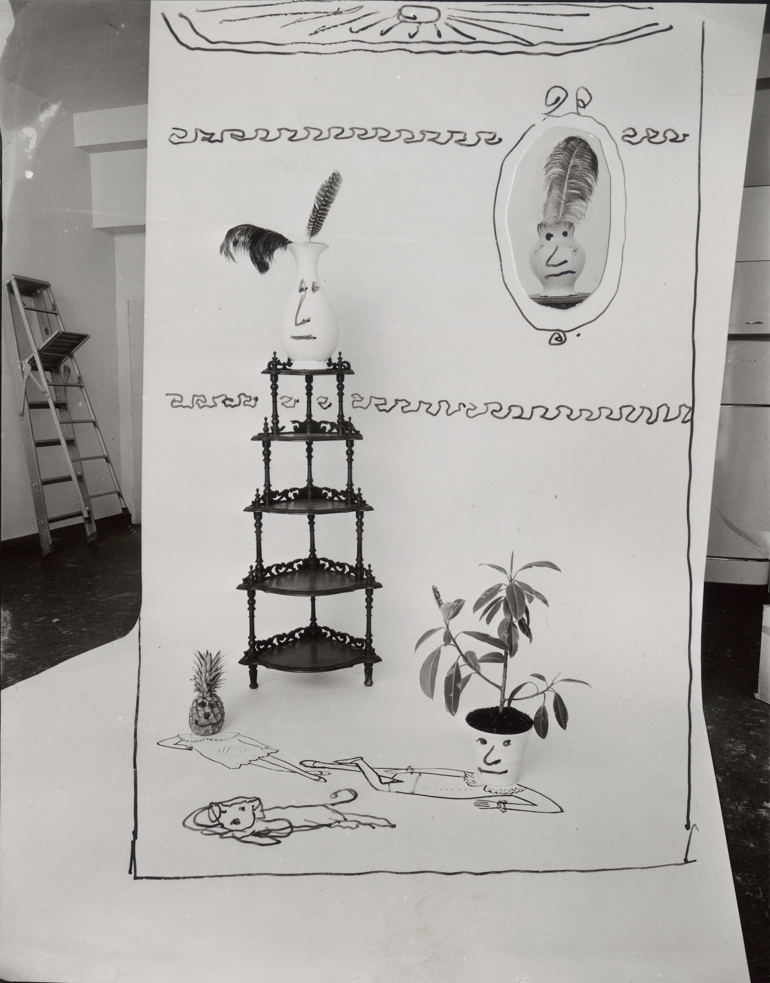

Untitled, 1950, gelatin silver print with hand-applied ink

In 1950, Steinberg was cast as Gene Kelly’s hand double for his painting scenes in An American in Paris. Los Angeles immersed the artist and his wife, Hedda, into a creative circle, including Charles and Ray Eames, who invited Steinberg to draw figures onto their fiberglass armchairs. This photograph from the same year manifests an illustrator’s urge to carry drawing into the third dimension, particularly in relation to architecture. Drawing comical facial and bodily traits onto inanimate objects, the artist suggests a light-hearted twist on the eventual isolation of time spent indoors. Steinberg’s approach to photography is equally whimsical and subversive, disrupting the aura of staged photography with the inclusion of mundane details from his apartment, most strikingly a ladder leaning on the wall. A wooden stand, a pot, and a vase—each “humanized” with eyes, noses and limbs—are juxtaposed into a domestic vignette, spread across a large paper scroll, which serves as the backdrop.

Untitled, 1950, gelatin silver print

Steinberg echoed his architectural training in his photographs of interiors, which he accentuated with drawings he directly applied onto surfaces. Before the late ‘70s when Gordon Matta-Clark captured the narrative of New York architecture and a group of photographers, loosely named The Pictures Generation clan, brought the workings of photography into the spotlight, Steinberg had already adopted brick walls and wooden staircases as canvases for his lens. This image of a woman he drew across what appears to be a stereotypical New York walk-up staircase is a photographic trompe-l’œil. The stairs’ geometric depth embodies a zigzagged state of intoxication, a hint the artist encapsulates with a glass of wine he playfully placed by the woman’s hand. His practice of depth and perspective would later yield set design, such as Jerome Robbins’s ballet, The Concert, and Rossini’s opera, Le Comte Ory.

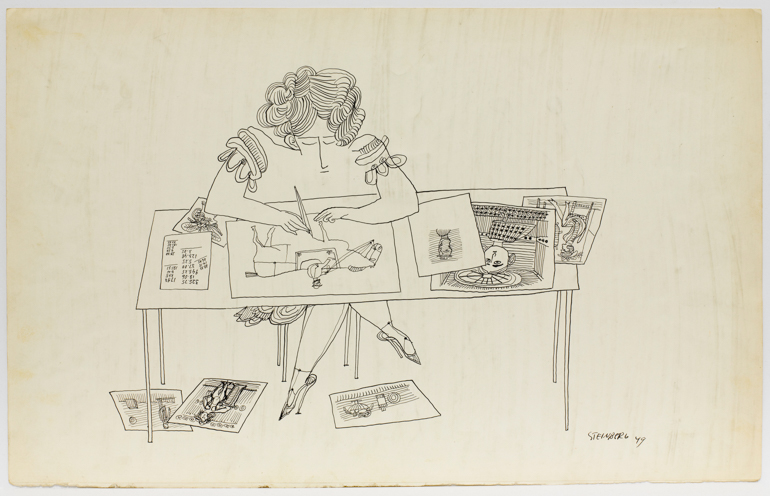

Untitled, 1949, ink on paper

The female figure recurred in Steinberg’s oeuvre to embody creative productivity or sexual mystery—often times anonymously—and with animal traits, similar to his various hybrid depictions of himself as an animal. The protagonist of this untitled drawing from 1949 is a woman ‘working from home,’ rather than pursing housework—a role associated with the American female workforce in the mid-century. The subject is engrossed in her drawing practice, a genre in which her expertise is made clear with Steinberg’s depiction of her amidst artworks overflowing from her desk. Drawings of sitters are noticeable, as well as a Cubist rendition of a horse. Curator Michaela Mohrmann notes the calculus sheet on the woman’s left, a signifier of autonomy and financial self-sufficiency for a prolific woman artist making a living through art. A year later, Steinberg revisited the same protagonist, covering her desk—in this version—with watercolor drawings of the human form, including a female nude and two Greco-Roman warriors.

Untitled (Victorian Interior), 1949-54, ink over pencil on paper

After seeing the group exhibition, “I Remember That: An Exhibition of Interiors of a Generation Ago” at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Steinberg was intrigued by the overlooked American artist Perkins Harnly’s watercolors of architectural extravagance. They were colorful, lush, and unabashedly flamboyant, brimming with impossibly ornate concepts of interior design. A general pursuer of balanced decoration, Steinberg flirted with the maximalism of Harnly’s brushstrokes in this drawing, a potpourri of objects occupying a living room in uncompromising density. The result is a demanding feast for the eye, an elated game to catch a harp with a woman-shaped pillar, a male bust with robust mustache, or a knight whose face resembles that of a frog’s.

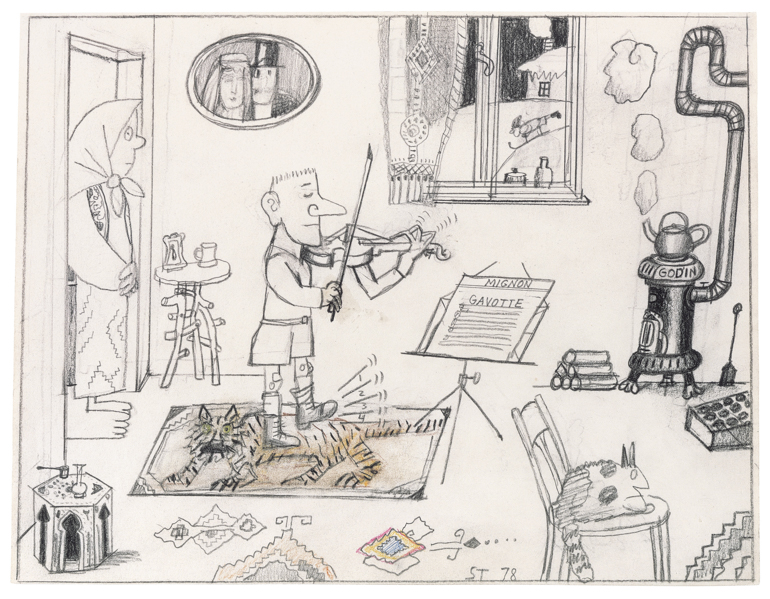

Untitled, 1978, pencil and colored pencil on paper

Steinberg had a complex relationship with Romania, which he considered “a primitive civilization,” a land of old world deprivation he “pledged to save himself from.” This homesick drawing of a childhood memory, however, is a love song to his humble background in the Eastern European countryside, visible from the window he carved inside a room imbued in nostalgia. A teapot boils atop a furnace; a tapestry adorned with an image of a leopard lies across a floor; a grumpy cat occupies a chair. On the verge of coming-of-age, Steinberg plays on violin Charles Louis Ambroise Thomas’s “Gavotte,” from his 1866 opera Mignon, watched by a barefoot female figure, whose facial expression hints maternal admiration. The fiery leopard on the floor— contrary to the room’s other feline—contains the volatility of teenage vigor, tapped by the violinist’s rhythmic foot (counting from 1 to 4) in accordance with his rapid finger gestures, suggested in the drawing with repeating curved lines.

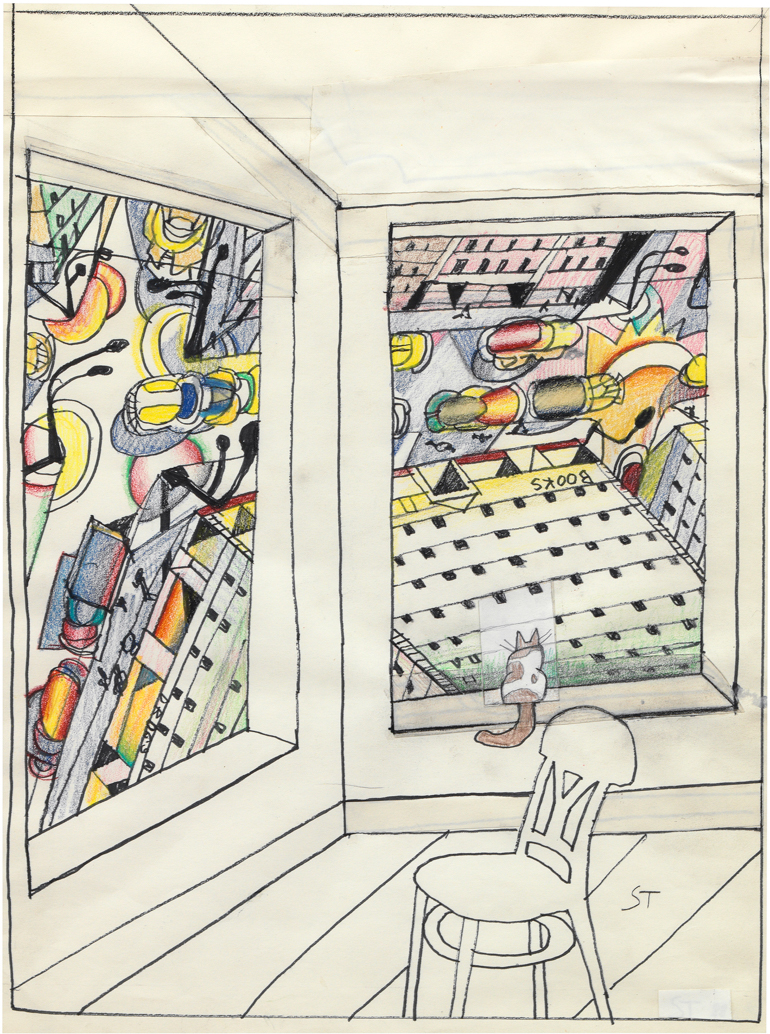

Looking Down, 1988, marker, crayon, colored pencil, and conté crayon with collage on paper

Avid dwellers of domestic life, cats frequently appear in Steinberg’s visual repertoire with their nonchalant attitude and disinterest with the outside world. A quintessential part of urban habitats, cats embrace the compactness of apartment-size living, undistracted by the bustle of social engagement. Looking Down (1988) catches a four-legged protagonist calmly overlooking a hectic New York from the comfort of its apartment window. Fast-paced cars, blasting lights, and high-rising skyscrapers rising through Midtown all seem too chaotic—and possibly unimpressive—for the lazy feline. Mohrmann points out the cat’s curved tail and the windows’ unusually large scale, which both serve as portals between two worlds inside and out, separated by the artist’s contrasting use of color and form. The drawing’s similarity to a 19th century Utagawa Hiroshige print of an Edo period brothel is not coincidental. In the early ‘80s, Steinberg created a series of drawings, entitled Rain on Hiroshige Bridge, inspired by the ukiyo-e print master’s rendition of perspective and depth.

Untitled, 1983, crayon, graphite and ink on paper

Steinberg never hesitated to flirt with Surrealism, depicting human and animal hybrids within absurdly mundane situations or attributing animate traits to architecture in his photographs. In this 1983 drawing, a classic mid-century living room awash in visual emblems of post-Bauhaus design is humorously interrupted by a farcical visit by Steinberg himself as a cat and a butterfly woman donning a stylish hat and hairdo. Her head stands in for the bug’s chest, sandwiched between elaborately-patterned wings spread above a Milo Baughman-inspired sofa. The chubby feline remains deadpan amidst the sleek Modernist setting, which contrasts the characters’ fabulist absurdism. The sliver of urban panorama outside the window hints they are on a high floor between similar apartment units in towering buildings.

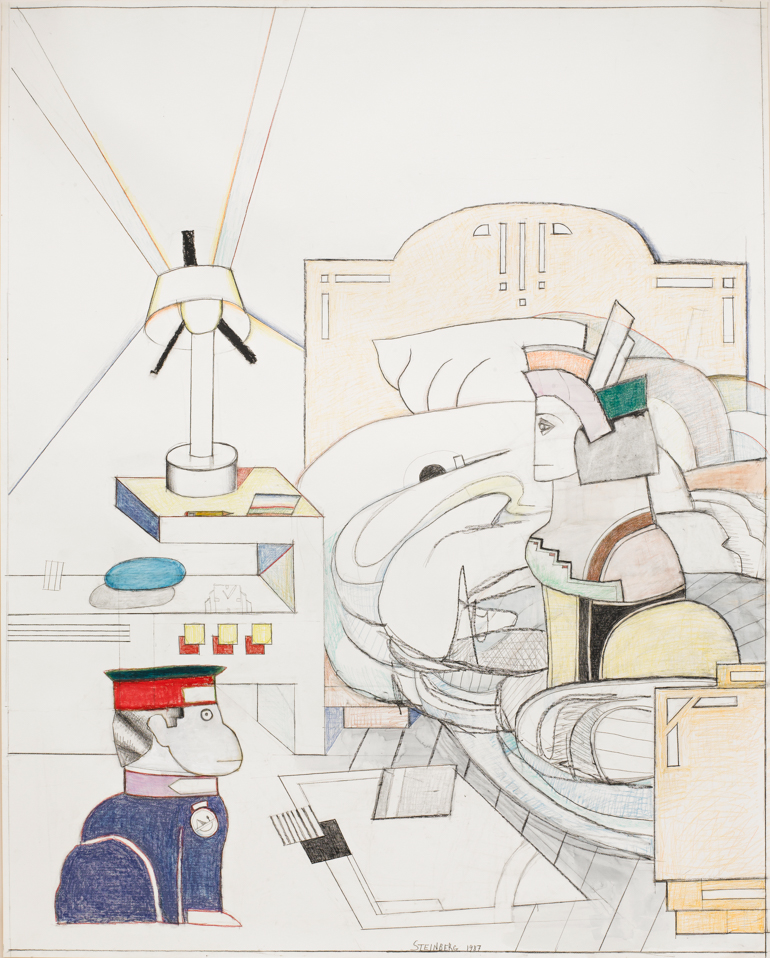

Bedroom Sphinx, 1987, oil on pastel, pencil and wash on paper

Architecture was not only a subject, but also a gesture for Steinberg, who used cues from building sketches in his illustrations of interiors as well as figures. In Bedroom Sphinx (1987), the sphinx’s form is built in Cubist manner, a style which has followed him since the Politecnico—a school he described as “under the influence of Cubism,” in the catalog essay of his 1978 eponymous Whitney exhibition. The bed frame’s round and sharp edges blend on a gilded palette a la Art Deco. The hotel room, in fact, is a medley of styles—from a Mid-century side lamp to a Cubist floor tapestry, or even a cluttered blanket for which Steinberg utilized the rapid gestures of the Abstract Expressionists, like de Kooning or Twombly. The monkey and dog hybrid bell boy’s intrusion into the hotel room and his admiring gaze towards the sphinx respond to Steinberg’s signature whimsical and subdued hint at sexuality.

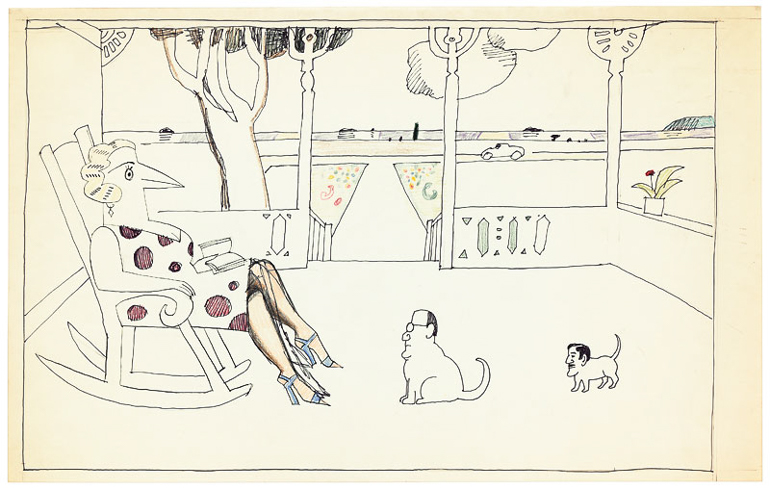

Untitled, 1983, crayon, graphite and ink on paper

An object of desire was a role Steinberg commonly attributed to his female subjects, whether they possessed complete human features or morphed into animals. A part of his “Domestic Animals” portfolio for a March 1983 issue of The New Yorker, this drawing takes viewers onto a porch, an epitome of American suburban life and a point of leisure. Here, the rocking chair is occupied by a woman in fishnet stockings and a deep V-neck dress, her head replaced by that of a bird’s. The woman’s wavy blonde hair compliments her inviting gesture. Her spectators are two small dogs, both donning male human heads. They watch the woman longingly, admiring her grandiose posture from an angle quite below her view of an eventless vista, unlike the urban chaos of a typical Steinberg work.

Chest of Drawers Cityscape, 1950, gelatin silver print

This is an example of Steinberg’s multidisciplinary approach to image-making, for which he utilized drawing and photography through the lens of his architectural training. This multilayered surrealistic image of Midtown Manhattan appeared in the September issue of the short-lived, avant-garde visual culture magazine, Flair. His process included photographing a tall cabinet with each of its drawers pulled out in increments and drawing architectural accents, such as windows and storefronts, onto its cutout print. He later surrounded the image with a bustling cityscape, occupied by staggered skyscrapers, pedestrians, and vehicles both on the ground and in air.

Read next: Odili Donald Odita Debuts New Work at Jack Shainman Gallery Spring Exhibition