10 Highlights from The Armory Show at Piers 90 and 94 in New York

Art enthusiasts once again convened at Piers 90 and 94 on Manhattan’s west side to take part in the city’s landmark art fair, The Armory Show, March 5-8. The fair, founded by four New York gallerists in 1994, has become a fixture in the city’s art scene as demonstrated by the high volume of people in attendance during its preview day March 4 despite concerns surrounding the coronavirus, which has led to cancellations of many global art fairs.

“I am very impressed by the outstanding quality of the presentations at this year’s fair. The art work on view will engage viewers and help to further solidify The Armory Show as New York’s essential art fair,” Nicole Berry, executive director of The Armory Show, told Interior Design. This year’s program includes 183 exhibitors from 32 countries, in addition to five curated sub-sections organized by different curators to emphasize emerging galleries from the United States and beyond.

Interior Design picked 10 highlight booths from The Armory Show.

Ed & Nancy Kienholz’s The Caddy Court at L.A. Louver

During the fair’s opening day, long lines curved in front of L.A. Louver’s presentation of Ed & Nancy Kienholz’s inviting installation The Caddy Court. Here Ed Kienholz draws on his fascination with cars to create tableaus that meld historical narratives with contemporary anxieties. Believing flea markets filter society’s energy, the artist often collected pieces from thrift shops with his wife Nancy while residing in Germany and the United States. The Caddy Court, comprised of an assembly of a 1978 Cadillac Fleetwood Brougham D’elgance and 1966 Dodge van, was custom-made in Los Angeles and finished at the couple’s Idaho studio between 1986 and 1987. The work features a dinner table-like assemblage inside the car—reminiscent of da Vinci’s The Last Supper—surrounded by the artists’ interpretation of U.S. Supreme Court justices from that era (think: taxidermy animals in suits and ties), all framed by the outline of a law school library in place of car doors.

Cassils’ The Resilience of the 20% at Ronald Feldman Gallery

Los Angeles-based Canadian artist Cassils, who goes by singular they pronouns, often challenges perceptions of the male and female form. The Resilience of the 20% (2016) at Ronald Feldman Gallery is an update on the artist’s ongoing Becoming an Image performances, in which they fiercely punch a large clay tower, fighting with the gooey material’s particular resilience with their trans masculine body. Repeating the performance one or two times a year, the artist tracks the change in their stamina due to aging by gradually lessening traces of punches over the clay. The bronze cast replica of the performative sculpture is exhibited in front of a wall-paper installation with images from the performance. The equally ethereal and grandiose sculpture is a testament to queer resilience and survival through physical activism and contemplation.

Joep van Lieshout’s The Leader at Carpenters Workshop Gallery

With locations in Europe and United States, Carpenters Workshop Gallery is one of the few present that showcases work by designers. The Carpenters Workshop Gallery booth at The Armory Show, which coincides with Joep van Lieshout’s solo exhibition The Good, The Bad, The Ugly, at its New York space, is dedicated to the Dutch artist and designer’s humous approach to depicting the human condition. Anchored by the large scale bronze sculpture The Leader, the booth is peppered with furniture and lighting fixtures that evoke similarly unsettling sentiments. The ghostly sculpture, with its drapery and darkened hollows, carries a chilling glare, offering a stark statement on mortality and power.

Oren Pinhassi’s Stalls at Edel Assanti

London’s Edel Assanti gallery exhibits a series of plaster-based mixed-media sculptures by New York artist Oren Pinhassi, whose amorphous forms disrupt corporeality, domesticity, and fulfillment. Colored in a pastel pink hue, Stalls (2020) is a comprised of three panels—or stalls—which the artist rendered transparent with a glass surface. Humanized by faint accents of bodily features, such as limbs, breasts, and genitalia, the sculpture reflects common domestic elements, such as a bathroom stall or shower divider. Accompanying Stalls (2020) is Pond (2020)—a sculpture that sits at the height of a coffee table and evokes a sense of fluidity with its glass surface. The piece, accentuated by empty toothbrush cup holders, builds on the theme of eerie domesticity, troubled by void and drought.

Kasmin Gallery’s Installation

Home is revived in a literal sense at Kasmin Gallery’s booth, where numerous artists, including Bernar Venet, Naama Tsabar, Bosco Sodi and Robert Mapplethorpe, are juxtaposed in a living room setting, finished with decorative accents and furnishings, particularly in wood. Small-scale works of photography, painting, and drawing orchestrate a domestic display, drawing unforeseeable parallels between the artists from disparate careers. An eerie photograph of a knee pushed into a wall by Tsabar, for example, is placed steps away from late French artist Claude Lalanne’s Lapin Debout I (2012), a whimsical bronze sculpture of a rabbit curiously carrying lettuce leaves on its neck.

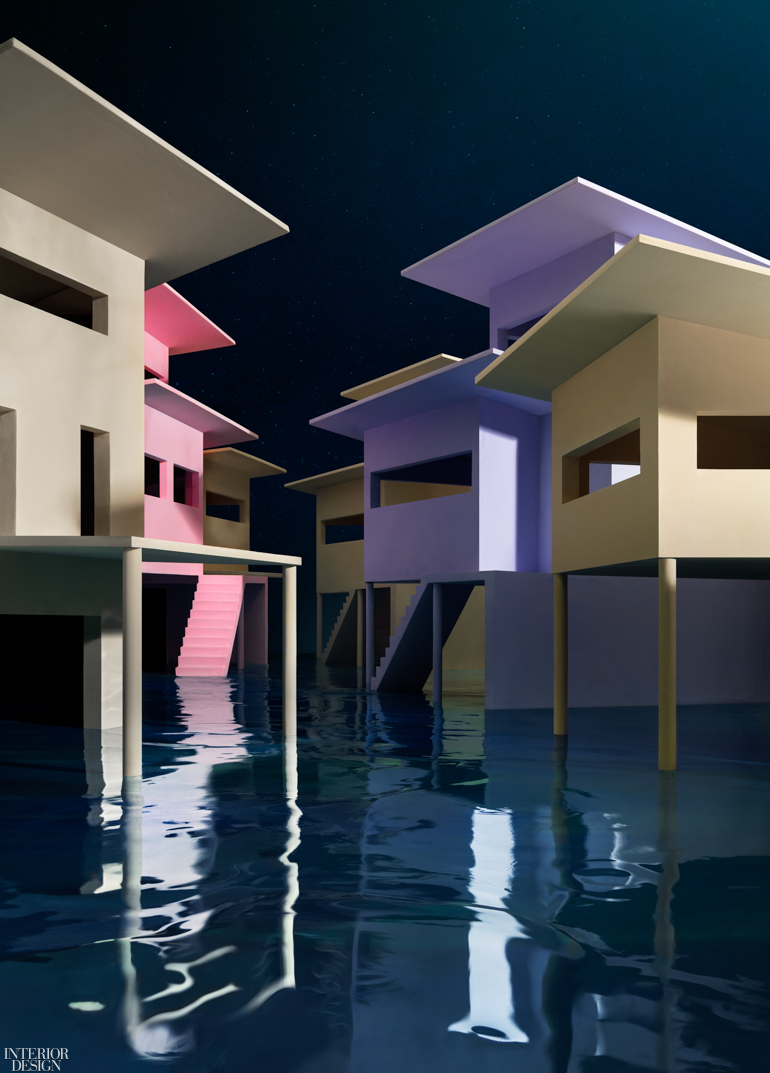

James Casebere’s Flooded Street at Sean Kelly

Architecture and interiors experience trouble in James Casebere’s serene yet alarming photograph, Flooded Street (2019) exhibited in Sean Kelly’s group presentation. Using staged photography, the artist first builds miniature architectural structures at his upstate New York studio, which reflect emblematic building aesthetics, such as Paul Rudolph’s Florida houses or traditional wooden homes in Norway. He “digs” his houses into a gelatinous material in order to convey a visual of water reaching towards the houses’ doorways. Casebere’s dramatic lighting techniques elevate the architectural perfection of his miniature structures, while the houses’ reflections in the liquid imbue a sense of calm and romanticism to an otherwise disturbing scenario of flood and interruption. Paris’s Galerie Templon currently is hosting a solo exhibition dedicated to Casebere’s series, fittingly titled On the Water’s Edge.

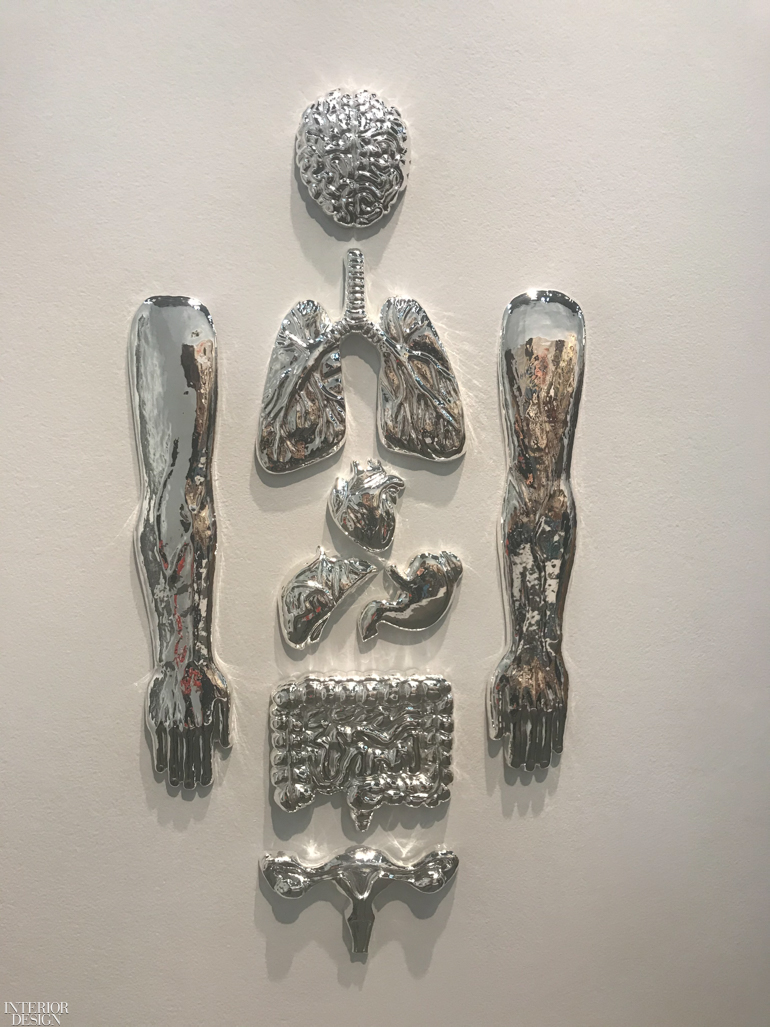

Prune Nourry’s The Miracle Organ at Galerie Templon

Galerie Templon also joins the fair with a group show of paintings and sculptures, which includes Brooklyn-based French artist Prune Nourry’s anatomical silver wall sculpture, The Miracle Organ (2020). Composed of various body parts, the artist’s constellation of the human interior starts with a brain and moves down to pelvis with two arms bookending a pair of lungs and the intestine. Surviving chemotherapy at early age, Nourry has been interested in workings of human body that stretch beyond definitions of medicine and technology, especially through bioethics. Unlike her widely-known larger scale sculptures, this wall-friendly work is intimate and inviting. The mirrored surface of the work reflects its surroundings, prompting contemplation about mysteries of human system below the skin.

Ayse Erkmen’s not the color it is series at Dirimart

The fair’s only Turkish gallery, Dirimart, exhibits a series of amorphous bronze sculptures by prominent Turkish contemporary artist, Ayse Erkmen. In various shapes and pastel hues, nine miniature terrain-like sculptures from the artist’s not the color it is series (2015) are exhibited on a pedestal, just inches above the floor. Despite their otherworldly appearances, Erkmen creates each nebulous shape through a meticulous process that starts with pouring bronze into holes she digs inside closed sand containers. She then lets the liquid take on its own unforeseeable form, adding color to each sculpture based on the Pantone system. The unpredictable nature of the work also is echoed in its gradual color formations, which occur after the Istanbul-based artist lets each sculpture rest. grass green / not the color it is, for example, recalls a mountainous pile of lettuce in a bright green tone; while rose pink / not the color it is mirrors an anatomical specimen, fleshy and unfamiliar.

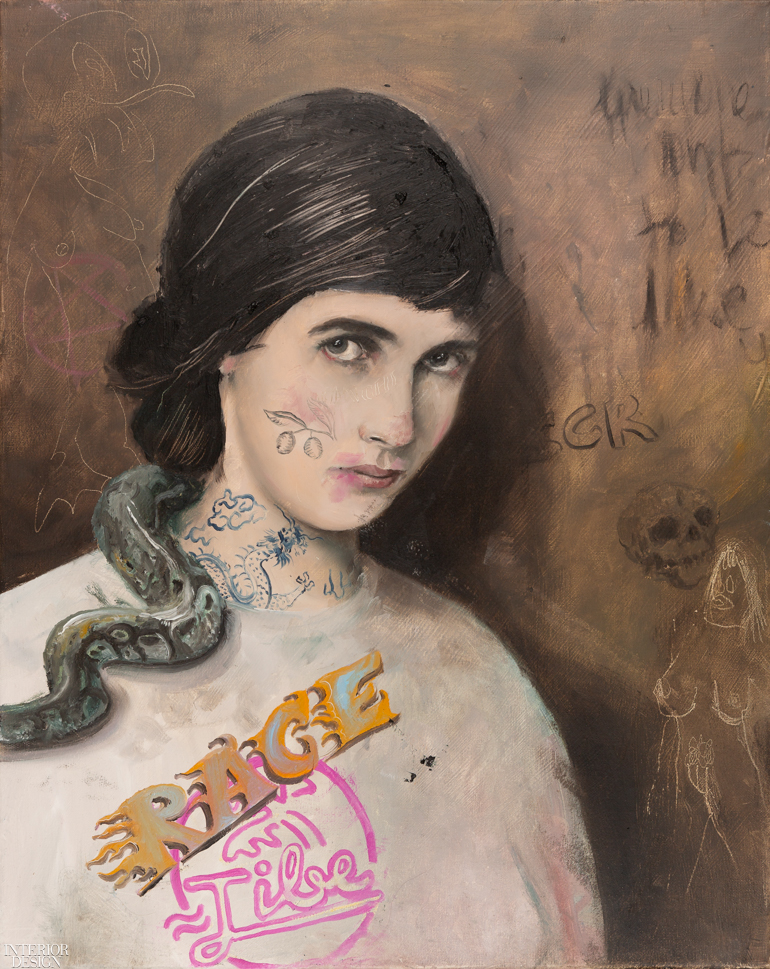

Philip Mueller’s painting installation at Carbon.12

Another visiting gallery in the fair is Dubai’s Carbon.12, which dedicates its booth to an immersive installation by young Austrian painter Philip Mueller, who takes cues from classical western painting as well as pop culture and kitsch. The booth features around 60 of the artist’s paintings in various sizes, including his takes on familiar faces, such as Grace Jones. Mueller often offers a contemporary twist on traditional European portraiture, for example, painting old wise men with voluminous beards, young doe-eyed girls who seem to stare at the viewer with halos hovering over their heads or biker tattoos adorning their necks. The artist paints his subjects as if they were so-called residents of his fictional beach resort Tiberio. Though Mueller’s painting gestures reflect traditional training, he subverts the expected with each dash of contemporary self-fashioning and anarchist text surrounding his subjects’ heads. In Tibe guest Marlene (2019), a young woman coyly looks straight ahead, while a snake crawls around her neck above the word “RAGE,” which is imposed on her chest in a bold font.

Melissa McGill’s Red Regatta at Mazzoleni

New York-based American artist Melissa McGill started her Red Regatta project in Venice in 2019. For the project, she collaborated with local art students and vaporetto sailors to activate four large-scale regattas of traditional vela al terzo sailboats in Venice’s lagoon. But unlike traditional vela al terzo boats, those created for McGill’s work featured hand-painted red sails, drawing attention to the city’s delicate relationship to its waterways. While New York City piers may be too small to accommodate McGill’s boats, Turin-based gallery Mazzoleni exhibits a selection of her photographic paintings from the project. In these, Venetian canals are hand-painted by the artist for added depth and impact, illuminating the reflection of the boat’s bold sails in contrast to the blue water.

Read next: 10 Highlights from Palais de la Porte Dorée’s Christian Louboutin Exhibition in Paris