10 Highlights from The Morgan Library & Museum’s Jean-Jacques Lequeu Exhibition: Visionary Architect

In Visionary Architect, The Morgan Library & Museum’s exhibition dedicated to Jean-Jacques Lequeu’s amusing drawings from the Bibliothèque nationale de France collection, note The Great Yawner. The pen and black ink self-portrait from 1792 depicts the 19th-century architect and draftsman yawning. And yet, Lequeu’s expression closely resembles a delirious cry, or a painful screech, embodying the overall elusiveness of his numerous architectural renderings on view in the New York City show. From otherworldly sphere temples to impossibly complex dairy barns, Leque envisioned unconventional buildings and interiors, transferring them onto paper with mathematical precision and poetic craftsmanship.

Coinciding with the cusp of the French Revolution, his arresting watercolor drawings functioned as architectural sketches, which he submitted to many competitions but never brought to fruition due to the era’s economic instabilities and, more importantly, Lequeu’s vivid imagination that defied engineering and architectural limits. Predating Surrealism in his utilization of subliminal visual cues—and therefore misunderstood by his peers, Lequeu eventually donated his 800 drawings to the French Royal Library, which became a national library after the Revolution. Totaling around 60, the drawings at The Morgan, mostly included in his never-published Civil Architecture book, range from meticulous imaginations of unrealized architectural forms to grotesque illustrations of human faces and bodies.

Here are 10 highlights from the exhibition, which runs through May 10, 2020.

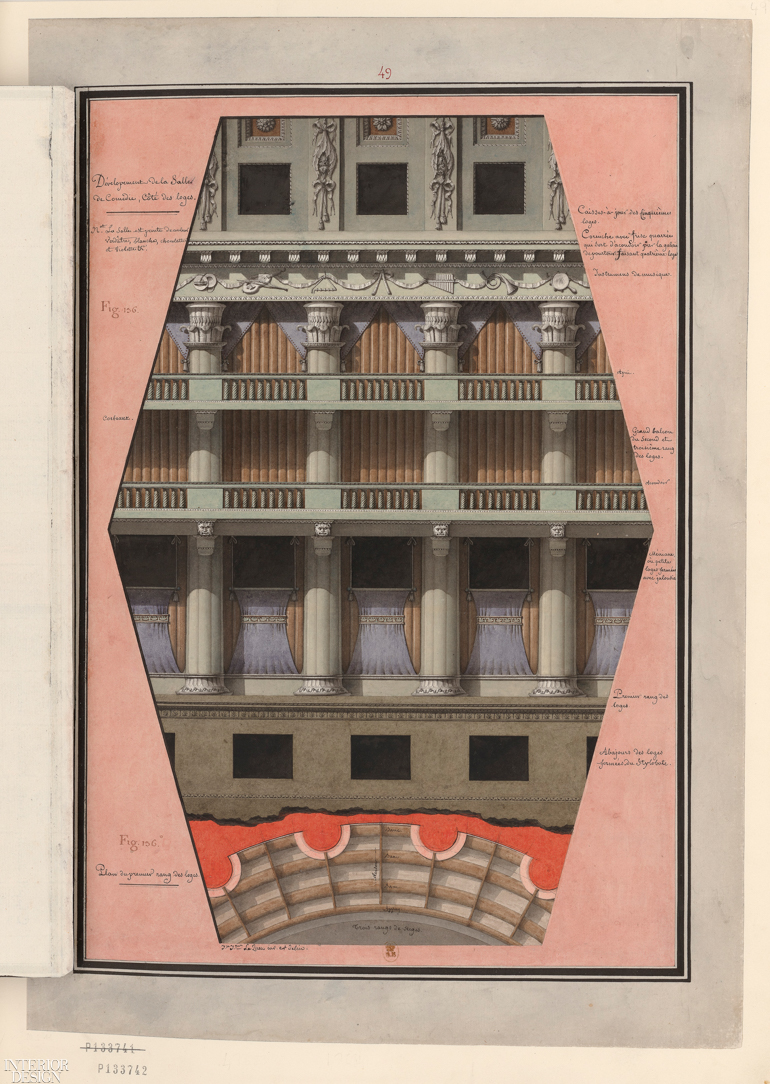

Design for a Theater Interior, from Civil Architecture

Lequeu’s preference for imagination and flamboyance over function is best indicated in his interior design for a theater. A drama enthusiast who wrote nine now-lost plays and designed theater sets, he envisioned an elongated seating arrangement, with five floors of chairs, box seats, and galleries, as typical in theater interiors. By limiting the gallery section seats to three rows, however, he suggested an architecturally counterproductive concept, which lends itself to an aesthetically captivating sketch of a towering structure, finished with elaborate column decorations and limited views of the show.

Chinese-Style Gardener’s House and a Terrace on the Banks of a River, from Civil Architecture

Evidence of Lequeu’s daytime job as a cartographer is notable in this complex detailing of a traditional Chinese architecture-inspired house, for which he employed ample imagination and intricate sketching techniques. Using Sir William Chambers’s descriptions of a Cantonese house from 1757 as a source, he imagined a multi-floor dwelling, lavishly crowned by animal heads dotting the cornices of the top floor while paying homage to geography with faux Chinese letters above windows. The terrace overlooks a river that reflects the house, which overall indicates the west’s convoluted interpretation of eastern cultures during the Enlightenment.

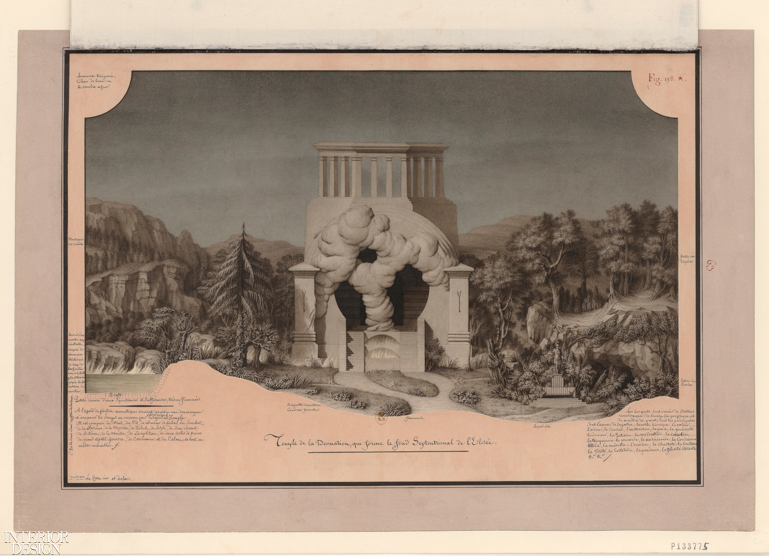

Temple of Divination (circa 1798-1802) from Civil Architecture

Trained as an architect at the Academy of Architecture, Lequeu was heavily influenced by built forms’ narrative possibilities, which he used for unleashing fantasies deemed absurd by the world outside his Paris apartment. This phantasmagorical concept of a temple for the initiation of ancient Greek priests acknowledges his celebration of mythical forces with an infernal architectural premise: A blazing fire roars on the ground floor, accentuated by bulbous smoke emerging toward the sky through a dome crowned by an array of columns. The solution he suggested to combat the fire’s bothersome odor was an aromatic perfume infused into air from the sanctuary—and the drawing includes a breakdown of ingredients.

Design for Living Room at the Hôtel de Montholon (1785)

Located on Boulevard Poissonnière in Paris’s 2nd arrondissement, Hôtel de Montholon still operates today as an extravagant example of pre-Revolution architecture, helmed by François Soufflot le Romain in 1785. Lequeu worked as a foreman for the hotel’s construction when he channeled signature elements of his fascination with antiquity into a design of one of its living rooms. Four caryatids gloriously substitute for columns, saluting the guests into an interior and imagined with such precision that visitors at The Morgan are offered magnifying glasses to enjoy its details. This curious space can only be appreciated on paper since the concept was never built inside the hotel.

Design for a Temple of the Earth, from Civil Architecture (1794)

The earth’s spherical form was an inspiration for Lequeu, who worked from his Paris apartment until his passing in 1826 with limited social life. He replicated the sphere in his building sketches as a tool to subvert prevalent aesthetic norms, which he reimagined with otherworldly elements and uncanny accents. He submitted this temple design to revolutionary authorities in 1794 as a “magnificent spectacle of a planetary model,” most vividly captured with the constellation of stars he aimed to create on the ceiling via sunlight streaming inside through numerous holes. Upon the submission’s refusal, he unsuccessfully re-submitted it in 1819 during the Restoration to an open call for a chapel honoring St. Louis in Paris’s Père-Lachaise Cemetery.

Study of Mouths, from New Method (1792)

Lequeu’s designs for buildings and interiors are among the most imaginative examples of a sub-genre known as “visionary (or speculative) architecture,” which is defined as architecture that does not correspond with engineering and utilitarian realities of the practice and lives on paper as mystical landscapes created with masterful hand gestures. A display of his talent for drawing is evident in a study of a mouth he approached with architectural precision and rendered from frontal and profile angles with help from a protractor. The study compares the perfectly curved arch of the lips to Cupid’s bow, delivering another example of Lequeu’s fascination with antiquity and its interpretation of bodily and architectural forms.

Squinting Man

In addition to The Great Yawner, Lequeu created various self-portraits in which he wore humorous expressions simultaneously referencing different human emotions thanks to his drawing acumen. Commitment to self-portrait is not surprising for a man who created his imaginary universes far from public eye; however, Lequeu’s expressive self-fashioning and dialogue with his viewers also taps into notions prevalent in today’s “selfie” culture. This drawing shows the subject in a squinting expression, his one eye tightly closed to convey doubt and farce as well as an invitation for closer inspection of his red chalk rendition of a human face.

And We Shall be Mothers Because…! (1793-94)

Lequeu drew numerous nudes, particularly of women, during his lifetime, many of which possess technical similarities with his imagination of buildings. This drawing of a nun bearing her décolleté is striking for signaling his approach to sexuality and religion, concepts he insistently handled with a dose of mystery. Created during the height of the French Revolution, the image of a nun choosing to reveal her own sexuality refers to the times’ shifting power dynamics between clergy and people of the First French Republic, which resulted in blood-drenched anticlerical executions both in Paris and outside the city.

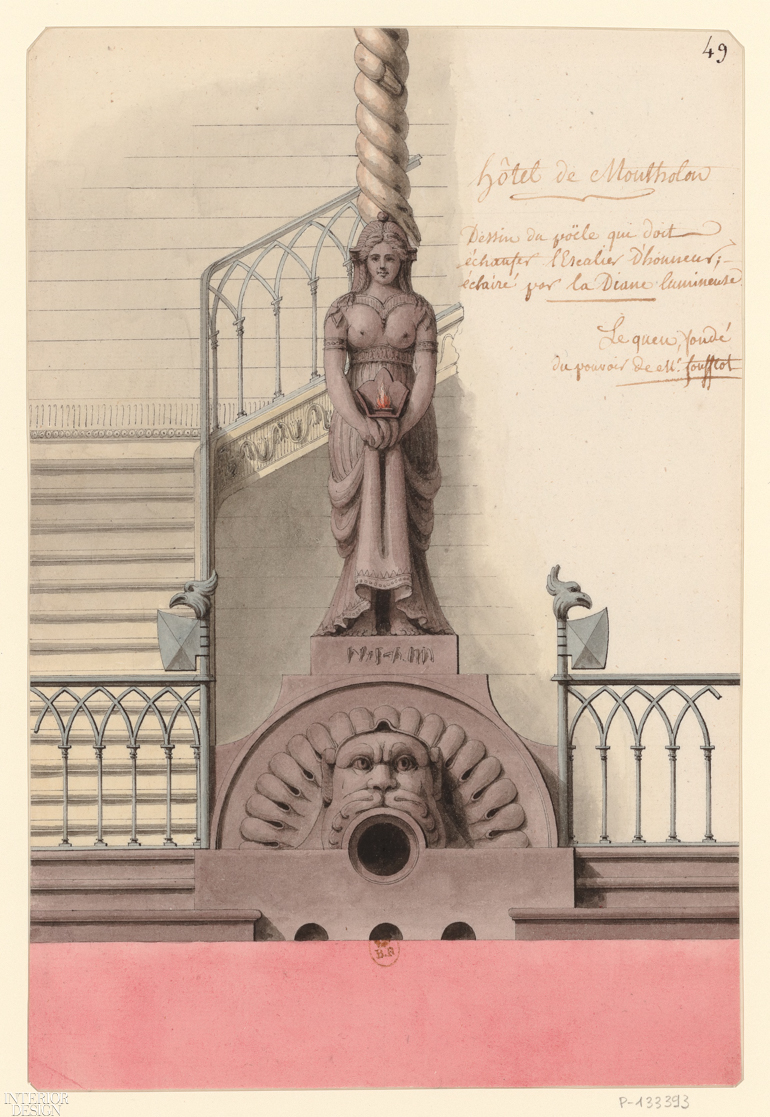

A Stove for the Ceremonial Staircase at the Hôtel de Montholon, 1785

Another heated balancing of sexuality and architecture is a stove Lequeuimagined for Hôtel de Montholon, for which he employed one of his favorite adornment techniques—the caryatid—in a performative fashion. Traditionally kept outside public areas at the time, stoves, or furnaces, served the architect as a tool for a playful interpretation of function. Here, he imagines Roman goddess Diana atop a creature while she holds an oil lamp, finished with a curved column growing above her head, similar to serpentine smoke blazing through fire. The figure’s association with chastity as well as childbirth and fertility correspond with fire’s productive and disruptive forces, creating a subtle, tongue-in-cheek comment on buildings’ corporal qualities.

Cow Barn and Gate to the Hunting Grounds, from Civil Architecture, circa 1815

Leuque aimed to push the limits of representation with this grandiose barn design that may read as “on the nose” for its minimalist eye or ahead of its time for enthusiasts of indulgent design. Inspired by Jean-Antoine Alavoine’s now bygone Elephant of the Bastille monument, the proposal suggested a barn in the form of a gigantic cow covered with an Indian blanket decorated in gold and silver, borrowing aesthetic inspiration from the east, similar to Alavoine’s celebration of “orientalist” cues in building a post-Revolution France. The hunting field is entered through a gate dotted with, fittingly, animal heads, such as boars and hounds, and was to be built in a mixture of limestone and sulfur, which he called “pork stone,” citing its smell, which he considered akin to cat urine.

Read more: 10 Artworks from ZONAMACO México Arte Contemporáneo and ZONAMACO Foto