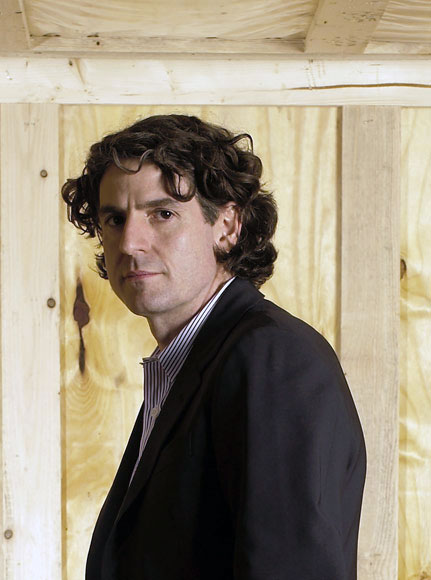

10 Qs with… Richard Wright

Wright’s Exhibition Space, preview for Important Design and Italian Masterworks auctions.

A visionary in the world of modern and contemporary design auctions, Richard Wright has grown his Chicago-based auction house,

Wright

, into a globally recognized source of 20th- and 21st-century furniture and art. After thirteen years in business as director and founder and 40,000 lots sold, he continues to grow his deliberate, thoughtful business and educate consumers on new genres of collecting.

Interior Design: Tell me about the inner working of Wright—how you’ve structured your company, and what type of employee helps it grow?

Richard Wright: We have 18 employees now, and many have been here a long time—hardly anyone ever leaves. A lot of our people have art degrees, and they’re these very visual people who have found their way to us. My number-one employee is a painter, who worked at an architectural bookstore, and bought stuff from us at our very first sale. His brother works for us now. We’re not a hierarchical organization; in fact there’s very little traditional corporate structure. I believe in individual responsibility—people knowing their role and wanting to do it. As I’ve gotten older, and weathered the financial crisis, it’s been an increasing point of pride that these people are a big part of my life.

ID: What’s the state of interiors auctions these days, following the recession of recent years?

RW: We’re back to conducting business in a way that is enjoyable. The creative end of it is the fun part, and it’s nice to think about the future. Running auctions is pretty demanding, and I’ve gone through periods where I’ve been less engaged and more engaged, and I feel in a really good place right now.

There were excesses in the market in 2006 and 2007. We don’t need to return there, and that shouldn’t be a benchmark. While a lack of fear is a good thing, consistency is preferable. What we really learned is the core value of the things that we sell—buying into a proven asset is going to hold value over time; supply drives demand. It’s still somewhat of an uncertain time, but people are spending again. There’s been a relatively fast rebound in values. We’ve seen special things standing the test of time, because at the end of the day it’s about the things that we really love. Thankfully, my team has never done “volume” to build revenue.

ID: How do encourage creativity among your team?

RW: I’ve learned through the years that part of being a leader is delegating and then letting go. That was hard for me at the beginning. You have to build trust in your best people, encourage them, and let them take chances. You also have to push people not to fall into a comfort zone. By my nature, I’m not one to be complacent, and am constantly challenging myself to be better. As an organization we ask, “How can we do it different, better… not cheaper? What’s something that no one else has done?”

ID: A big part of your company is dedicated to educating your consumers about 20th Century furniture, art, and design. How do you approach this task?

RW: I’m really proud of the educational side of it, and the growth potential of the content we create. I find our print catalog to be a gorgeous, wonderful animal, and have come to have great respect for graphic design. Trying to unlock a comparable format on the Internet is the next challenge. We’re proud to be a huge part of the online research one can now find online. We share our images liberally and like to spread the word.

When I opened in 2000, I didn’t appreciate how small the market was and how much room it had to grow. I had been a dealer and worked at another auction house, and the escalation in values was striking. I wish I could have predicted it more. Things became very expensive and serious, with whole new categories of collecting emerging. Paul Evans comes to mind, whose stuff I always liked but was hard to sell in 2000. Now it’s become a real collecting field in its own right. Maria Pergay has set records in the market, and previously I didn’t even know about her.

ID: What is the selection process like with your auction items?

RW: It all starts with desirability, and we have set criteria of what we’re looking for. We meet a few times a week to discuss what’s come our way, most of which comes through email. There are three buckets: stuff we know we don’t want, the maybes, and the yeses. There will be slam-dunks, but in general we meet and discuss everything. If we decide to move ahead, we get more information about the condition of a piece and the history behind it. There are definitely instances of copying out there, so we watch for that. Since we’re not the only auction house out there, we talk to sellers about why they should choose us to sell that piece, produce print-on-demand books to win consignments, then make a proposal.

ID: What kind of rapport do you like to create with clients?

RW: What I like about the auction world is that our interests are aligned with those of sellers. The better I do my job, the happier you’ll be, so we’re on the same side of the table. I enjoy crafting these deals, and figuring people out. Some look for the attention of a sale, while others are strictly about the money.

ID: What’s your approach to creating enthusiasm for big-ticket pieces?

RW: From the start, we think about how we can best position a piece in the market. We’ll do dedicated marketing for it, which has proven to ba really effective. Recently, we took a chance and sold a Ford concept car, the Ford Gyron. There was no way to benchmark it; it was this weird, quirky concept car that was never produced. The end results of our efforts yielded far beyond what we imagined we would get. It was a nice confirmation of the work we do. I feel really good when I do well, with the things that are within my control. There are many factors outside of my control, and sure, great results are great, but you have to feel proud of your effort first and foremost.

Wright’s Exhibition Space, preview for Important Design and Italian Masterworks auctions.

ID: What do you see for Wright in the coming years?

RW: Our big, overarching goal is to unlock the potential of our website, and I want to continue to foster careful growth. I made that decision a while ago. I have young children, and like living a balanced life. I’m ambitious, but I’m not looking to make it a huge company; there are no plans to open in New York or LA. I’m grateful to have the company I have. I’d like to do more auctions, but smaller, more targeted ones, that are about collections. We recently did an Italian masterworks sales of thirty-five lots from one man’s collection… Our book was really special; we presented it in a fresh way and sold it well. All I could think was, Damn, that’s fun. I want to do more of that.

There’ll be a push this spring to grow out the gallery aspect of the auction house. There is a lot of material we have access to that isn’t well suited to auction, and there’s a growing market for items between auction. For an interiors professional, it’s hard to get a client interested in a piece that may not remain available, and the same goes for curators.

ID: What is your take on the designers of this generation? What are you drawn to?

RW: The end of contemporary design that exists in the auction world has gone through a tough few years. A lot of it got over-hyped and then badly punished. Then again, there are many examples of great designers of our generation not doing purposely-conceived design for really rich people, and that is inspiring. That resonates like nothing else. On a personal level, I’ve gotten more interested in an antiquer’s view of modernism, the things that can’t be reproduced and show their age in a wonderful way. It’s like a folk art type of modernism, braiding together the rigor of modernism with the soulfulness of things from the past that carry their history on the surface. My fascination with this might be a sign of my getting older. I also love Prouvé as a collecting field, this super-industrial design with soul. So much of it looks better the more it’s been used.

ID: When did you first get really inspired by great design?

RW: When I moved to Chicago, the Mies Van der Rohe buildings spoke to me on an architectural level. I often get lost with Mies—the richness of the material, the absolute purity of his design. He can make stainless steel look so good; the choices are incredible—the wood, the fabric, the leather. Some modernism can be dehumanizing, but the best of it is quite the opposite. I also think that travel to Europe, seeing the way modernity exists with history, has a big impact on me. I recall going to Demark and being so exhilarated to see that modernism was just a part of the culture—like capitalism is here! It’s like, “Look, every light fixture is Henriksen, not a copy.” Then there’s Italy, where the gesture of the contemporary can resonate so beautifully in those settings.