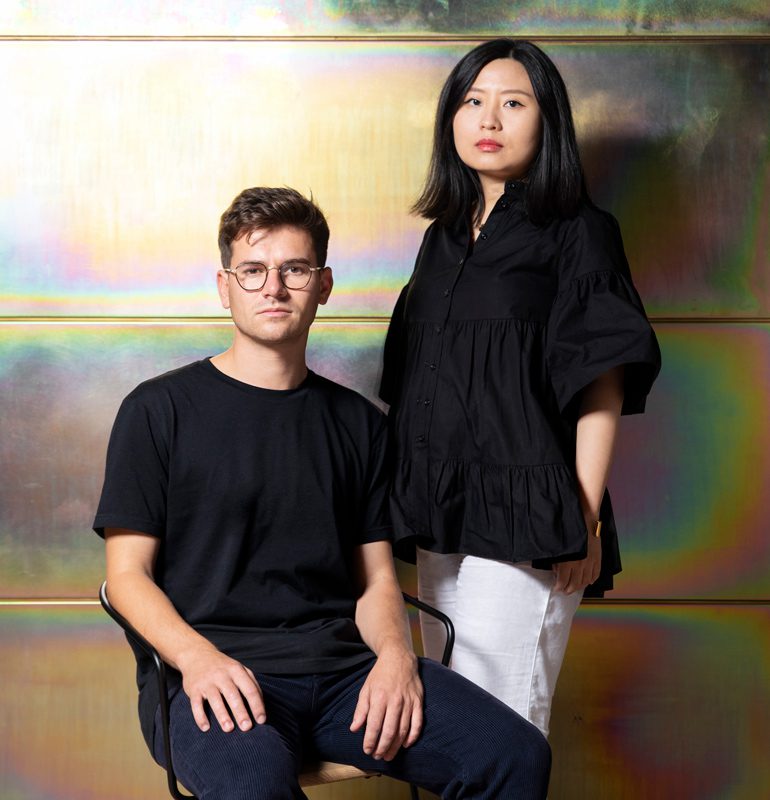

10 Questions With… Alex Holloway and Na Li of Holloway Li

When it came to designing a sustainable urban retreat in the heart of Bermondsey, London, designers Alex Holloway and Na Li turned to the rock formations and sandy roads of Joshua Tree in California for inspiration. Guided by desert aesthetics and sustainable design principles, the pair, who cofounded their practice Holloway Li in 2015, transformed the 143-room hotel into a relaxing haven with repurposed materials throughout.

When it came to designing a sustainable urban retreat in the heart of Bermondsey, London, designers Alex Holloway and Na Li turned to the rock formations and sandy roads of Joshua Tree in California for inspiration. Guided by desert aesthetics and sustainable design principles, the pair, who cofounded their practice Holloway Li in 2015, transformed the 143-room hotel into a relaxing haven with repurposed materials throughout.

Inventive use of concrete testing cubes that would otherwise have ended up in the landfill and repurposed steel rebar add intrigue to the space, which features a hypnotic iridescent wall, enabling guests to experience a desertlike mirage. Bermonds Locke hotel, which opened last fall, is just one example of the designers’ abilities to blur boundaries between residential and hospitality design, historic and modern spaces, as well as upcycled pieces and technological innovations to create complex, layered interiors.

Currently, the firm has projects underway in London, Munich, and Beijing. Here, Holloway and Li share with Interior Design projects leading the way in sustainable rooftop design, the influence of film director Stanley Kubrick, and the benefits of repurposing basic construction materials.

Get to Know Holloway Li Cofounders

Interior Design: What led you to establish a design practice together in 2015?

Na Li: We actually followed very similar paths into design, both studying architecture at The Bartlett where we learned to create amazing design work and a lot of it—at top speed. The institution’s hothousing effect propelled us forward, both working on pretty substantial projects at a relatively early stage in our careers. We didn’t actually meet until we found ourselves designing Soho Farmhouse together while apprenticing at Michaelis Boyd. I designed the Main Barn, and Alex designed the gym there. We built a respect and trust in our partnership during that time.

Alex and I set up separate practices in 2015, but through sharing an office space, we began collaborating informally. During that time, we built complete confidence in each other with our work ethic, aesthetic and spirit all aligned. We made our partnership official in 2018 and Holloway Li was born.

ID: What do you consider instrumental to the success and growth of your business?

Alex Holloway: I think the most important factor in our success thus far is the interplay between our cross-cultural backgrounds. We like to experiment with different themes, blurring the boundaries between historicism, decoration, and digital process. Our work is characterized by an eye for detail, which I think has helped us win projects. We like to think each space we design is intricate, engaged, and impactful invoking fresh and contemporary forms of experience. London is an undeniable and ever-evolving stylistic influence for both of us—particularly as our team is more often than not working on existing buildings with a storied past, we look to play with the dynamic conflict between old and new, fusing historic vernacular with contemporary intervention to create a new narrative.

ID: Where did your interest in design begin?

NL: I was born in Nanjing, China, and even from a young age I knew I wanted to pursue a career in design; it has always been something I’ve felt passionate about. I graduated from University College London (Bartlett School of Architecture), becoming a qualified architect before embarking on the start of my career at developer-led Architects Teatum & Teatum, Wilkinson Eyre, and later Michaelis Boyd where I worked across the Groucho member’s club, and Soho Farmhouse in Oxfordshire.

AH: I studied at both The Bartlett and RCA before honing my craft at large architectural practices like Michaelis Boyd, John McAslan+Partners, Pernilla Ohrstedt, and Perkins and Will—working across commercial hospitality and high-end residential market, with clients including the Soho House Group and projects such as Battersea Power Station redevelopment, and UniCredit HQ (Milan). I had a fairly religious upbringing and it’s only recently dawned on me that the pomp and ornament of the Catholic church might have had a subconscious influence on my propensity for decoration over restraint.

ID: How do you begin each project; what is your creative process?

AH: Site visits are important for us, to understand the area, the host building and what we have to work with. With each project, we undertake extensive and immersive research, we’re interested in new finishes and new materials. Devising inventive new processes is a cornerstone of our work and we’re proud of how this translates into rich and varied interiors that invite guests to return again and again.

That being said, we are inspired heavily by art, film, and notions of shared and lived experience. I am always drawn back to two primary influences: film director Stanley Kubrick and performance artist Matthew Barney. I have inherited Kubrick’s fascination with single-point perspective—a symmetrical vista—this is a common theme that runs through a lot of our studio’s work.

I love Barney’s process because of the detail and dedication of craft in order to create such vivid depictions of imagined worlds. The precision that went into the sets created for “The Cremaster Cycle” show total commitment to his vision.

ID: Bermonds Locke hotel opened in London last year, how did you arrive at Joshua Tree as a design inspiration?

NL: The host building was a shell office block, built five years previous and unoccupied—this blank, concrete canvas gave us a rare opportunity to take a left-field visual approach. We eschewed traditional London vernacular tropes and prevailing design trends, looking further afield for our inspirations, to create a new space that had an escapist identity. Joshua Tree has been a recluse for fringe creatives escaping L.A. for the past 30 years. We were particularly interested in the eccentric language of bricolage found in desert cabins dotted around Joshua Tree, composed of salvaged materials that happen to be available by chance.

ID: In what ways does Bermonds Locke represent a new direction for your firm’s work?

AH: The Bermonds Locke project was a chance for us to really put into practice the studio’s recent research on the circular material economy—how we can re-use building materials that would otherwise be discarded. Design in this context becomes almost like a curatorial practice, about how an existing set of materials can be rearranged in a very specific way to define new uses.

Placing an emphasis on low-cost and low-impact, we developed ideas around how we could repurpose basic construction materials, processes, and waste in unexpected ways to create bespoke insertions and furniture pieces. To give an example, we recycled concrete strength-testing cubes to create table plinths in the co-working area and the bar-front in the restaurant, referencing rocky desert outcrops. We love the humble story of these waste elements, each cube has a unique sand/cement mix and is numbered and dated with a different set of handwriting, following a strict 100 x 100mm form. This consistency made them the perfect element to re-purpose for meaningful use. The concrete testing facility was particularly helpful in stockpiling these for us, when they would usually go straight to landfill.

ID: How do you incorporate sustainable practices and upcycling into your projects?

NL: We now set ourselves a sustainability innovation brief at the start of each project. We are definitely becoming more proactively sustainable in our approach. In the world of interior design and fit-out, you quickly become aware of the five-year refurb cycle. Spaces change hands and once again everything is ripped out and started over, but this approach is changing. We want to make sure every project has an element of re-use or upcycling that highlights the circular material economy.

Sustainability can also be about low-cost, and low impact—doing more, with less. Sourcing locally, is something that we are keen to emphasize. We would love to do a project where everything is recycled, and devise inventive new processes that become a testbed for new practice.

ID: How has the pandemic impacted your approach to hospitality design?

AH: What travelers and patrons want is quickly evolving—privacy is the new luxury. We love working on evolving briefs that challenge and motivate us to test and innovate. As hoteliers and restaurateurs recognize the need to raise the bar to attract trade, we’re excited to take risks and work on more progressive projects and exploring our love for material innovation.

ID: What are you most looking forward to in the coming months—either professionally or personally?

AH: We have just finished our design for a rooftop bar extension for The Hoxton, Shoreditch, and we’re looking forward to having a drink there in the not too distant future. We hope this will become a case-study for sustainable rooftop development in London, and an exemplar for activating dormant London commercial roof space in our capital. The challenge was to design an additive structure that “plugged-in” to the existing structural and service capacity of the host building, exploiting the buildings embodied carbon with a zero-waste approach to construction debris.

We are also becoming increasingly interested in the world of modular “off-site” construction. We are designing the interiors for the U.K.’s first high-end modular apartment hotel in Canary Wharf—290 rooms are made entirely off-site as separate modules and then craned into place like giant lego blocks. This approach massively reduces construction waste, whilst allowing for a huge level of quality control over the finished product. It’s a great way to work, and you will be seeing more and more of it in the coming years.

At the other end of the scale we are designing a Bakery in Notting Hill. It will be the first international outpost for Georgian brand Entrée. The interiors were inspired by an immersive trip to Tbilisi. We can’t wait to see it come to life.

ID: What are you reading now?

AH: I tend to have a novel and something non-fiction on the go at the same time. Currently I’m reading “A Little Life” which is a dense yet poignant examination of the friendship of four friends (one an overworked architect) in their post-college years trying to make it in the world—it’s very well-observed.

To offset, I’ve almost finished Adam Grant’s “Originals,” which is a powerful thesis on how to recognize originality and the benefits of a non-conformist approach. It’s one of those books where you have to stop and think after every few pages so it’s taken a while to make progress. Anyone with a rebellious streak and ambition will find excitement in it.