10 Questions With… Architect Francis Kéré

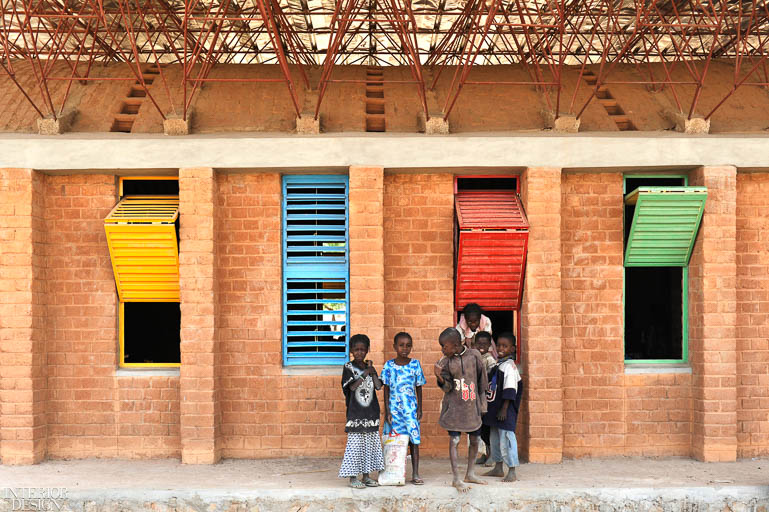

“They need evidence; without it, they don’t believe,” Francis Kéré says, speaking to ways he’s gained trust—and support—from local communities for his architectural projects. “They need to see it to believe it.” It’s this communal approach to design that enables the internationally acclaimed architect, born in Gando, Burkina Faso in West Africa, to create spaces that meld seamlessly with their surroundings, using local and natural materials whenever possible.

“They need evidence; without it, they don’t believe,” Francis Kéré says, speaking to ways he’s gained trust—and support—from local communities for his architectural projects. “They need to see it to believe it.” It’s this communal approach to design that enables the internationally acclaimed architect, born in Gando, Burkina Faso in West Africa, to create spaces that meld seamlessly with their surroundings, using local and natural materials whenever possible.

After working as a carpenter for many years, Kéré earned his architectural degree in Berlin in 2004, where he then established his firm: Kéré Architecture. His acclaimed designs include those for the Burkina Faso National Assembly, the Léo Surgical Clinic & Health Centre (2014), the Lycée Schorge Secondary School (2016), a visitors pavilion for the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival (2018), and Xylem (2019), a gathering pavilion for the Tippet Rise Art Center in Montana.

Kéré’s work often blurs the line between architecture and art. His projects have been featured in group exhibitions such as: AFRICA: Architecture, Culture and Identity, at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk (2015), Small Scale, Big Change: New Architectures of Social Engagement, at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (2010) and Sensing Spaces at the Royal Academy, London (2014). During the Interior Design Show (IDS) in Toronto, Kéré sat down with Interior Design to share insights into his creative process, preferred materials, and the importance of education.

[Editor’s note: Kéré earned this year’s Pritzker Architecture Prize as announced March 15, 2022. “Francis Kéré is pioneering architecture—sustainable to the earth and its inhabitants—in lands of extreme scarcity. He is equally architect and servant, improving upon the lives and experiences of countless citizens in a region of the world that is at times forgotten,” states Tom Pritzker, chairman of The Hyatt Foundation, which sponsors the award. “Through buildings that demonstrate beauty, modesty, boldness and invention, and by the integrity of his architecture and geste, Kéré gracefully upholds the mission of this Prize.”]

Interior Design: When did you first discover the world of architecture and become interested in it?

Francis Kere: Wow, that is a delicate question… In my case, it was simple. I left my parents when I was seven to go to school. While doing this, I had to work on the weekend. Some of the work I was doing was to provide the construction site of my guest family with construction materials. And believe me, I hated it. As a kid, I wanted to play soccer like everyone else. In my subconscious, I grew the idea to make things better, so they don’t need to be fixed all the time, and the kids would play and not help build… Another experience is the school itself that I attended, which was hot and dark inside. Not a good place, and my subconscious was telling me: ‘If you become a big man one day, you make it better.’ … Then, when I got a scholarship to go to Germany to do vocational training, I wanted to know more about construction. It was for carpentry, but I said: ‘Okay. Building itself. I want to know how,’ and they said: ‘No. You have to study’ … I wanted to become an architect, to go straight back home and start to improve everything that I had experienced as a kid.

ID: Do you think your childhood influences your design thinking now?

FK: Yes, of course. [I think about how to] make it in a way that it lasts longer; that is stable; that it convinces people that it serves people; that is not hot inside; that it comes out with less maintenance. Yes, of course. My childhood influences my design thinking a lot.

ID: How would you describe your communal approach to design?

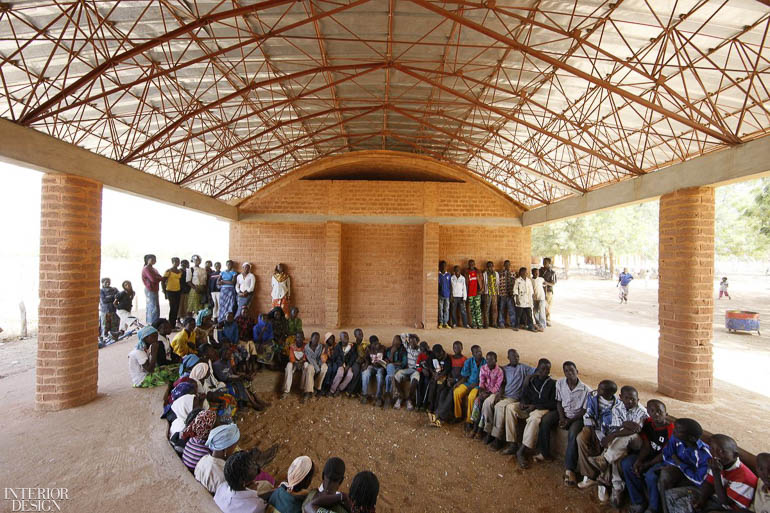

FK: I have to say, that is the intellectual narrative that we have now. At the beginning, it was not like this. Being an undergraduate student, you have a big heart for your community. And you go back. You want to use your skills to build at school. And you have no resources. But you remember, as a child, everyone that was building something—building a structure, or doing labor-intensive activities—would require the support of the entire community. So, I say everyone should come and help… You’ve got to tackle this challenge of building a school and having less money. So that’s how it really started. I have to mobilize everyone, and I realized with time: Okay, because they were doing it and they did it, the fear—that is ours, and the common sense—this is ours. ‘Wow. We did it.’ And they start to sort of take ownership, to protect the building, to appreciate it, and to be proud of it. Since that time, I always try to communicate wherever I go and to get people involved.

ID: Education has obviously played a big role in your career, whether building schools or with your teaching. What is the power of education for you?

FK: High, very high. I, myself, through education and architecture study, was able to do what I’m doing. Normally, you would follow your grandfather or your grandmother throughout their long life to be able to do that. That is one thing education enabled me to do. But… they favor pushing men [rather than women] in education. Even with the men, it is very limited. In my case, [people] attacked my father when he sent me to school. They were saying he’s stupid—why is he sending his first son to school instead of letting him work on the field to feed the family? Now my daughter can be a state employee and bring money home and have better education for her own kids and be independent and not depend on a man. For me, that illustrates the value of education. It’s so important, but access to education is still a dream in many, many places in Africa.

ID: It’s interesting because you were talking earlier today about innovation and how the use of clay is innovative, which shows innovation can come in a lot of different forms. It’s not just about technology, correct?

FK: Yes, of course. That is a Western failure, to think that what is working here—we just take it and bring it there, and then it will develop. It is innovation…. You need to be able to manage innovation, to manage sophisticated things. The danger with this inability [to do so] is that everyone that has a voice, and maybe has more power, will promote everything if you allow them to… Thanks to Google, I can show you the development of my areas, and it’s great, but let’s give communities, poor communities, [opportunity] to build up what will help them most. That is innovation.

ID: The challenges of building environmentally sustainable buildings in places like West Africa, is it just inherent in the building materials?

FK: It is important. If you use locally available materials and you improve them, so you are improving the cultural heritage, that is what we’re proud of. Why are we proud to be American? Because we have a cultural background, something that unites us… So, we have something in common—an identity. If we reinforce that cultural glue, then we are making a community strong. A stronger community is capable of surviving, is tolerant, is welcoming, because it can resist any challenges. It’s a healthier community, and it is community that will support our world to grow in peace with each other.

ID: You have these projects you’re doing, but you’re doing things like Tippet Rise and Coachella, since now you’re a cool dad, but it seems like you’re approaching those kinds of projects in a similar manner or are you doing it differently?

FK: Yes, because I want to see the site. Even Coachella, I wanted to know what it is. Tippet Rise, of course, I went there many, many times. And I had very great, very visionary clients. They allowed me to come many, many times to see how the elements affect the site, to explore available material—dead forest, burned down forests—and what can we use. To see the site in wintertime, summertime, in spring, in between—they allowed me to do all of that. So this is common to every project that I’m doing. I want to see the site. But some regions, I know already. I don’t need to just go through there… And then the material approach. I’m looking at what is available, really. If you work with—used to work with—scarcity, your approach to architecture is for sure different. And later what is different is if I work in a sophisticated world like the U.S., you have plenty of knowledgeable people. They can do it and that was a great, great, great advantage in Montana. You have people that could translate your ideas into reality… if you have people that know the rules of architecture or the art of architecture and are compelled to think outside the box, you could create great things.

ID: Do you have a favorite material to work with?

FK: I do. I mean, if I have to do housing or whatever in West Africa, I look [to see] if it’s a culture of clay and if it is abundant and people can handle it. I try to improve it. I will use laterite. I will use a granite stone because it’s available and then I will use even wood, local wood that is available. If I do a pavilion in London, you can just use wood in a very sophisticated way than you will do in Ghana, in Burkina Faso, in all West Africa…Because if this realization is at the high level, then I try to change that in this way. To use something in a very different way, like our Serpentine Pavilion where everyone is talking about textile. A wooden log that looks slightly like textile because it’s light, warm at the same time—embracing.

ID: What are you working on for the future then; are you still working on the IT University project in Burkina Faso?

FK: Yeah. It’s still ongoing. We’re doing two auditoriums, one for 100 students, and one for 200 capacity. We’re pulling these now, actually. But now is 15 years of the existence of my office studio, officially. And for this reason, I’m trying to finish some ongoing projects in Gando. I have a project that is coupled with the Xylem Pavilion in Tippet Rise because the same client says, ‘Let do two projects, one for Tippet Rise and then another one for your village.’ I’m working on that; it’s a high school. This is a great project and I hope within this year or, at least the middle of next year, to finish because my primary school will be 20 years old—my very first project… We’re doing a lot of projects across the country, but now more and more projects in Europe.

ID: Do you have a dream project that you would love to do?

FK: Yes, my dream project is to work with a client who is visionary enough to work with [me] and allow things to happen… This is always a dream project—just to work hand-in-hand, and to challenge the usual way of making things, and to create something new. Every time, that is always my dream project.

Read more: 10 Questions With… Naoko Takenouchi and Marc Webb