10 Questions With…Arthur Mamou-Mani

“Sure 3D-printing can spark the imagination, but there are many types of 3D-printing,” says architect Arthur Mamou-Mani. Working out of a 2,200-square foot hangar in Bethnal Green, London’s East End, the Paris-born architect and founder of architecture and design studio Mamou-Mani and printer service company FabPub loves showing this technology’s untapped potential in unexpected ways. From a majestic temple at the Burning Man festival in Nevada to an installation for fashion label COS that drew crowds at the Milan Furniture Fair, his visually arresting, highly original projects have brought global attention to the process of making three dimensional architecture from a digital file.

Most recently, as part of the 2021 edition of the London Design Festival, Mamou-Mani strung up 3D-printed bioplastic beehives in the atrium of the flagship of upmarket department store Fortnum & Mason for his installation “Mellifera: The Dancing Beehives.” Made of sugar, the beehives can be composted at the end of their lifecycle.

Interior Design sat down with Mamou-Mani to learn more about his Fortnum & Mason installation, how he ended up building a temple at the Burning Man festival, and what he is 3D-printing for the renovation of his home.

Interior Design: How did you choose the distinctive beehive geometry of “Mellifera: The Dancing Beehives,” your installation in the atrium of Fortnum & Mason?

Arthur Mamou-Mani: Fortnum & Mason is an iconic, very British store near Piccadilly Circus in London. When we visited, we were invited upstairs where—surprising and surreal for the middle of London—they have beehives. Fortnum & Mason produces their own honey and auctions it off to raise money to help bees in general, which I thought was really great, so we decided to do a project that would reflect this initiative.

“Mellifera” consists of 50 giant beehive-type modules 3D-printed from bioplastics made from fermented sugar. They’re almost 16 inches wide and around two feet high—that’s the maximum size that we could print—and suspended from cables. In the shop’s 56-foot-high atrium, they rise from the ground all the way to the skylight which is close to where the bees actually are. They start in tight together and then they slowly get more spaced out as if they were pulled by the skylight. There’s a beautiful motif in the atrium that was inspired by champagne flutes, so we tried to reproduce the geometry. We have a crusher in our studio, so we are constantly crushing our bioplastic waste and reusing it—bioplastics can be reused about five times before you have to compost. However, this piece will be auctioned off and 25 percent of the profits will go directly to a charity.

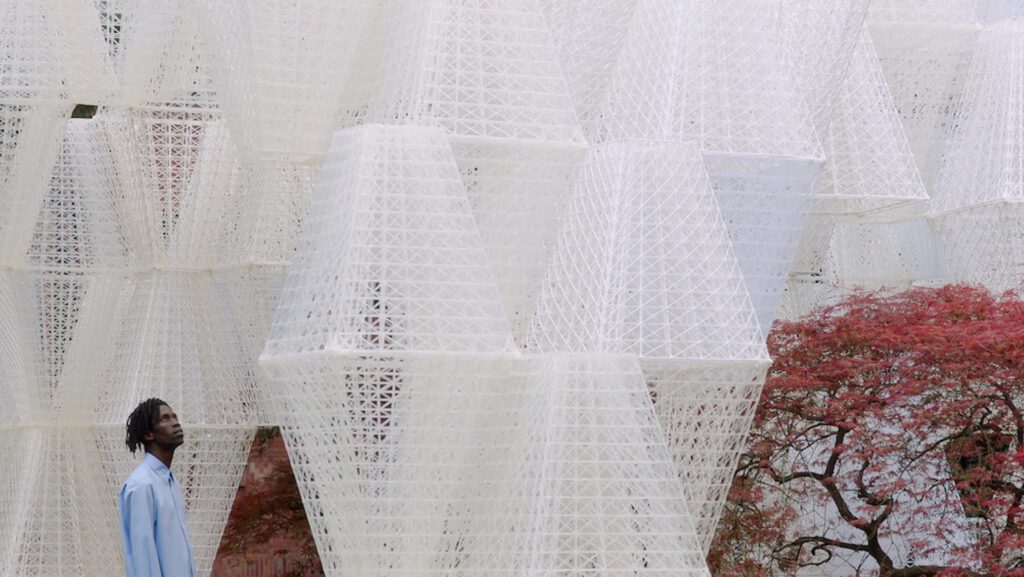

ID: How does this project compare to “Conifera,” your installation presented by COS in Milan in 2019, which also used repetition of 3D-printed objects?

AM: For the COS project, which was more about the craft, we used a much larger printer because the available space was larger and outside. Since “Mellifera” is within the interior of a luxury department store, we wanted to demonstrate another aspect of our technology. We wanted to produce a piece that can show that 3D-printing can produce silky smooth finishes that appear really refined. We also used two smaller printers, working nonstop, printing the entire project in-house through FabPub. It’s quite a challenge to print that many pieces so fast. For “Conifera,” we had to use these little pellets; for “Mellifera,” it was filaments which are much more delicate and can print at a much higher resolution. The result looks almost like it’s made of silk.

ID: Your installation for the Burning Man festival in 2018 was an internet sensation.

AM: I teach at the University of Westminster and we started going to Burning Man with our students. Of course, it’s often seen as a festival or a party, but actually it has a lot of underlying principles like leaving no trace and radical self-reliance. Imagine a city that builds itself in a week and then unbuilds itself. That’s exactly what the idea of circular economy is—thinking about the afterlife of things and understanding where your waste is going. There’s something really interesting about being in a city where you have to deal with your own waste, it makes you think of the bigger picture. Galaxia, at 32,000 square feet and almost 200 feet wide and 65 feet high, was built by 180 volunteers in 18 days in the desert, fully self-funded through crowdfunding. It was sort of a secular space without a religion but was used as a temple. People were placing offerings or writing inside the space. It was a really wonderful, unusual type of space in a city that’s itself unusual.

ID: What else have you worked on recently?

AM: During the COVID crisis, there was a shortage of masks in the U.K. because they were being shipped from other countries like China. With FabPub, it’s almost like having a mini factory in the middle of the city, so we could produce masks at cost for hospitals. The situation really proved that having your own 3D-printers could actually help with the production of things, despite the blockages from a crisis like COVID. By decentralizing factories, everyone can have a little factory nearby. In a way, COVID was a great moment to show the importance of digital fabrication. This has empowered designers to produce in-house as opposed to rely on mass production.

We always try and think about good local materials or something that could help people see things differently. In Saudi Arabia, they have so much sand and deserts. Just before COVID-19, we printed “Sandwaves,” which we designed with Chris Precht of Austria-based firm Precht. It was urban furniture [created] using sand and a binder. The structures were almost like three-dimensional leafs—natural structures that seemed to have thickened where they needed to thicken. We used the computer to help simulate structural performance. Using a lattice-like structure, the computer helped us understand where we need more or less thickness. So we created these almost natural-looking curved benches that were playing with local vegetation like palm trees and dancing around like waves, hence “Sandwaves.”

ID: What’s upcoming for you?

AM: We’re doing a reclaimed timber tower in Bali, Indonesia. There was an unused timber structure bridge from colonial times. We undid all that and then reused the material to build anew.

In October, we’ll be doing a piece for the atrium of The Design Museum in London as well, also printed in bioplastics. For a project at the new headquarters for Orange, a large telecommunications company in France, we’re doing something in steam-bent timber.

ID: Instagram suggests you have a major renovation underway at home.

AM: My wife, Sandy, and I are renovating our Victorian home in Stoke Newington in East London, and some of the exciting things I’m sharing via my Instagram stories. Replacing the back facade with reclaimed timber from old train tracks, we opened it up to the courtyard. To gain light, we dug below the street level. This is the first time that I have focused so much on an interior and it’s so hard. We’re replacing plaster boards and doing everything with clay. There are pipes with ducts full of hot water, and then you have clay render on top of that—so the walls are like heated skin but made of earth. Clay is the most environmental thing there is—no paint, no toxic material. Plus, it absorbs and purifies the air and heats up a space in a uniform way. A lot of what we are using is from research that we did for eco materials. We have recycled glass tiles in the bathroom and we 3D-printed the balustrade to our staircase. The project is a proper experiment into an environmental home, which is a bit crazy because it was very expensive, but we’re trying to see what is affordable and what is not in order to learn how we could bring this to people.

ID: How did your childhood or formative years influence your design thinking?

AM: I grew up in Paris, and my dad is a computer scientist and my mom is an ecologist….yes, now my career makes sense. She worked for the Ministry of the Environment and he had a computer science company. I was also really lucky to study at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London, which has teachers with a very different way of thinking who taught me that anything can be a source of inspiration—not necessarily existing designs or other architects, [but] something like nature. It’s really important to have those teachers that kind of tell you that you can think beyond the box.

As for becoming an architect, there’s not that many jobs for someone into science and math and art with an equal passion for all. It was always an obvious vocation for me, although no one in my family is an architect.

ID: Who in the industry do you particularly admire?

AM: I’m just back from Arles, France where I saw the new Luma Arles tower by American architect Frank Gehry…It’s incredible how Gehry—probably the only architect that is known by the general public as a name—can connect. In Arles, people are just in awe; he really transformed the city from one people might not necessarily know to a place they want to go. It’s not just about his building, but also how he celebrates the heritage of a space. This tower refers back to Vincent van Gogh’s brush stroke because he painted most of his paintings in Arles—Gehry celebrates that through the use of the bricks.

ID: What are you reading?

AM: “Art as Experience” by John Dewey, an old book that I just recently came across on the same trip at the Foundation Vincent van Gogh Arles. It’s about how art should not be put on a pedestal because it is part of our everyday life, and part of all the objects that we see. You can have an artistic or an aesthetic emotion in front of things that are not necessarily put in a museum or celebrated as art. I find that idea really powerful because I feel like we tend to disconnect the artistic and the scientific…or determine who is an artist type or who is not the artist kind of person. I’ve always thought these were arbitrary barriers that prevent us from being creative or being an active participant. In the stuff we buy, for example, we become quite passive consumers. This book is expressing the idea that we can all be artists, that we can all have an artistic approach to life.

Burning Man has this notion of ‘radical participation,’ so that there’s no spectator in the city and everyone is the artist of the city. I find it really important to not disconnect people from what is otherwise seen as artistic creation versus something we can all create together.

ID: Do you have a secret you can share?

AM: I’ve probably done over 700 Google reviews. I don’t know why, but I really enjoying doing them and now I’m a ‘Level Seven’ reviewer. I’m obsessed! They’re basically my travel diary. Sandy is a real foodie, and she always tells me: ‘I don’t want you to buy me anything, just experiences.’ This is one way to keep track of all these experiences.

more

DesignWire

Design Reads: A Closer Look at Jasper Morrison’s Work

Discover British designer Jasper Morrison’s wide range of furnishings, homes, and housewares in his cheeky retrospective “A Book of Things.”

DesignWire

Eco-Friendly Pavilions Take The Stage At A Chinese Music Festival

For a Chinese island music festival, Also Architects crafts reusable, modular pavilions that provided shade while resembling sound waves.

DesignWire

Meet The Production Designer For Wes Anderson’s New Film

Legendary production designer Adam Stockhausen shares how he crafted Wes Anderson’s The Phoenician Scheme’s cinematic world through spatial design.