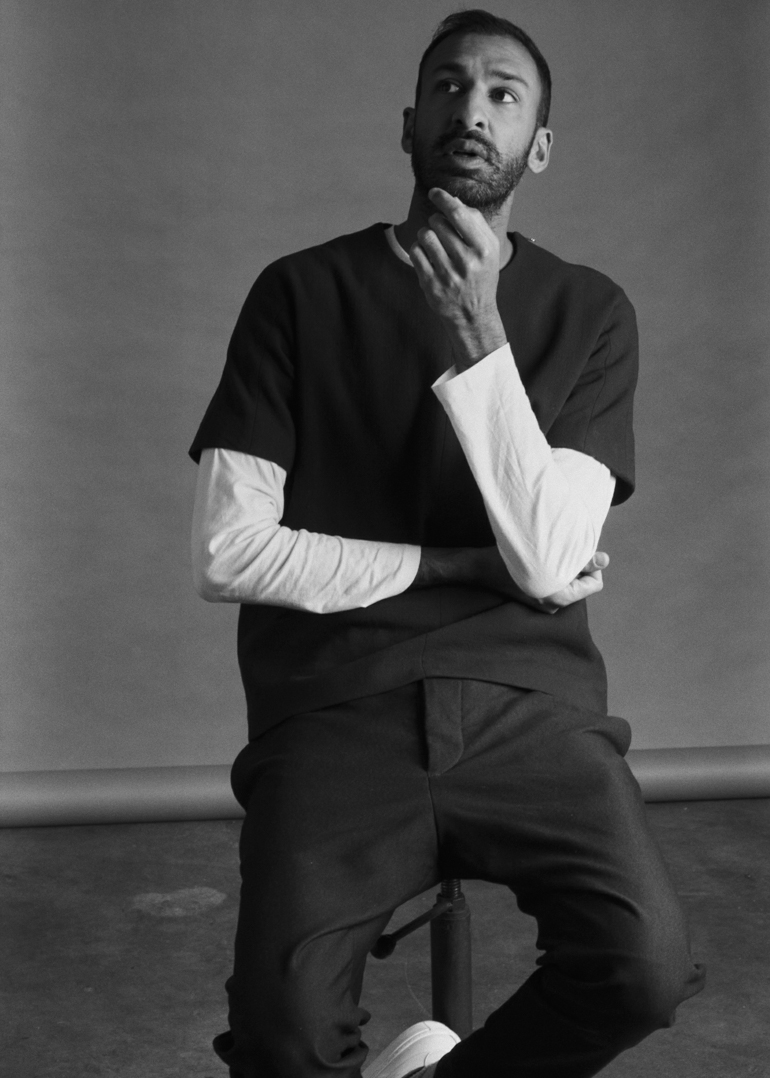

10 Questions With… Asif Khan

London-based Asif Khan describes his studio as having fortuitously secured ever larger projects over the past 10 years, culminating with its present design for what has been deemed the largest event to be held in the Arab world: Expo 2020 Dubai, postponed until October 1, 2021 due to the pandemic. Helmed by Asif Khan himself, the studio has spent three years applying its calculated R&D-based approach to the Expo’s 1,000-acre site while working on the new 258,000-square-foot Museum of London and a 10,800-square-foot exhibition for African ceramics at Munich’s Design Museum, Die Neue Sammlung. Khan compares delivering such large-scale projects to a moon landing, noting that a singular vision is fundamental to bringing all stakeholders together.

London-based Asif Khan describes his studio as having fortuitously secured ever larger projects over the past 10 years, culminating with its present design for what has been deemed the largest event to be held in the Arab world: Expo 2020 Dubai, postponed until October 1, 2021 due to the pandemic. Helmed by Asif Khan himself, the studio has spent three years applying its calculated R&D-based approach to the Expo’s 1,000-acre site while working on the new 258,000-square-foot Museum of London and a 10,800-square-foot exhibition for African ceramics at Munich’s Design Museum, Die Neue Sammlung. Khan compares delivering such large-scale projects to a moon landing, noting that a singular vision is fundamental to bringing all stakeholders together.

Singular is a good way to describe Khan’s experience designing pavilions. His studio is responsible for the award-winning U.K. Pavilion at Astana Expo 2017, the Hyundai Pavilion at the PyeongChang 2018 Winter Olympics, the ‘MegaFaces’ Pavilion at the Sochi 2014 Winter Olympics, the Coca-Cola Beatbox at London 2012 Olympics, and the 2016 Serpentine Gallery Summer Pavilion, just to name a few. For Expo 2020 Dubai, Khan began with the massive Expo Entry Portals. Next year, the two doors, each measuring almost 70 feet high and 34 feet wide, will open each day of the Expo in a symbolic act of welcoming the world. Here, Khan lets us in on how he designed the Expo to help visitors to discover the region’s past and future through sensory experiences.

Editor’s note: This conversation has been edited and condensed.

Interior Design: What role do you think Expo 2020 Dubai plays for the local population?

Asif Khan: One of the first things we did when we began work on Expo 2020 Dubai design three years ago was to plot a map showing the location of all past World Expos. When you see the map, you can’t help being struck by the absence of dots at the center of the world—the whole of the Middle East and North Africa. Understanding that this would truly be the first expo in the region made me feel we had a bigger task to achieve: to introduce the world to the unique ideas and heritage of the region, perhaps for many visitors for the first time.

An even stronger feeling was that we might be able to create a Public Realm that could also connect with visitors from the region itself in a new way, to realize a sense of pride and energize them, as the unique and beautiful aspects of their culture—the landscape, the language, the religion, the architecture, the history—are celebrated. I think this is what World Expos are about.

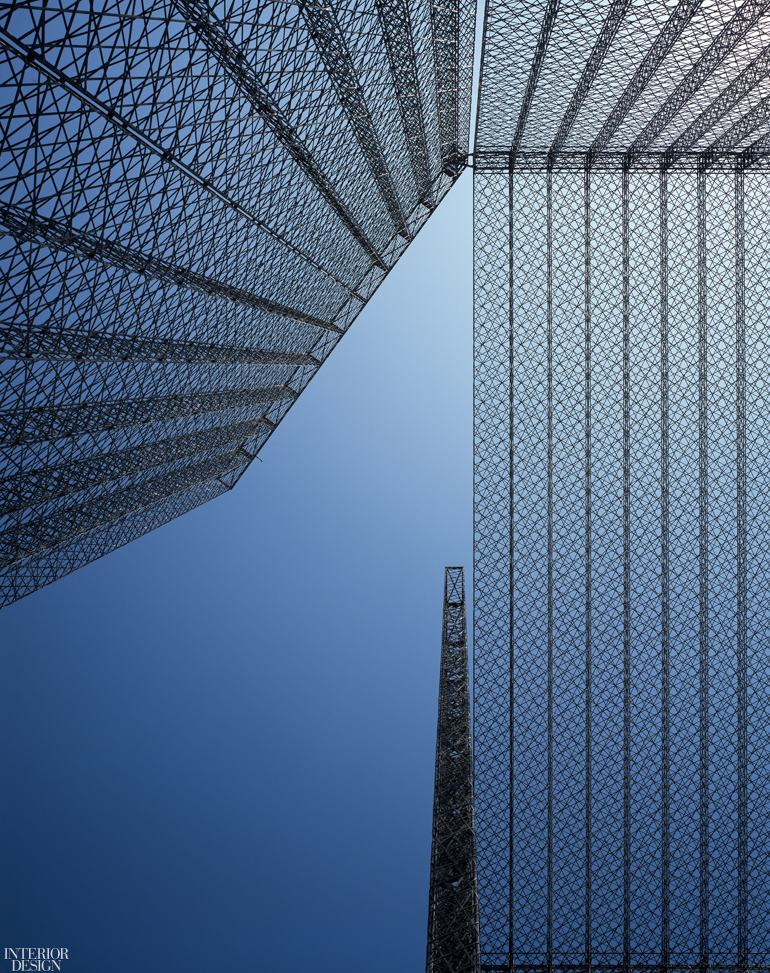

- Expo 2020 Dubai Entry Portals designed by Asif Khan. Photography by Helene Binet.

ID: How did local cultural influences shape your design for the Entry Portals?

AK: The forms are inspired by the region’s mashrabiya, architectural elements that passively provide shade, increase airflow, and enhance spatial difference through a nested system of repeated geometric and structural components. They are beautiful, highly functional, and inextricably part of an aesthetic language that has crossed the region for centuries.

The Expo Entry Portals began life on my desk as a tracery of Islamic geometry on a piece of black paper that I scored and folded into three dimensions. We had been researching entryways into homes, forts, and palaces in the region. The sequence of moving from the outside, through a large door and portal into an interior courtyard is a spatial archetype of the Islamic world that I felt we had to let visitors begin their journey with. The moment of doors opening and moving from one condition of light and temperature to another, a simple yet powerful threshold, is so exciting to think of as the entrance to the World Expo.

ID: What are some of the structural challenges in a project so vast?

AK: Our proposal was to use carbon-fiber filament to enable the portals to be self-supporting, at an incredible scale and thinness. By using a 3D-winding manufacturing process, every line of geometry would be drawn by machine into the lines of the structure and then would appear like lines drawn in the sky. Working with a fantastic carbon-fiber manufacturer, Ha-Co GmbH, and structural engineer Calin Gologan from the aviation industry, and with the huge support and determination of Expo 2020 Dubai, we were able to bring it to life.

ID: Can you describe your design for the Expo’s Public Realm a bit?

AK: Once through the portals, visitors will reach three tree-filled, shaded arrival courtyards, each with service buildings and picnic areas for schoolchildren under the shade. In the Mobility District, visitors will encounter moving grasses; in the Opportunity District they will discover regional flora like the Ghaf tree; and in the Sustainability District they will find medicinal and aromatic plants such as the neem tree.

The Public Realm has been designed to give millions of visitors a deep experience of the region, full of stories and unexpected experiences, from the design of the concourses you walk on, to the benches you sit on, the planting, and the lighting. The main concourses are the extensive 3.5-mile walking routes everyone will use to move around the Expo. The design was developed following my first visit to the site before anything was built. Walking on the desert sand barefoot, I felt connected at that moment with a deep history of place. I realized that I was leaving tracks in the landscape like many others had before me. The Expo’s main concourse design references those lines crossing the desert, the movement of people, animals, goods, and ideas, leaving tracks across the sand.

ID: Aside from the Expo, you’ve designed quite an extensive portfolio of pavilions. Any favorites?

AK: Historically, architects have always used pavilions and temporary structures as prototypes for new technologies and aesthetics. In the past five years I have been wanting to create experiences which challenge our relationship with nature and to do so at a scale which feels all-encompassing and real. In 2018, our studio designed a pavilion for the car company Hyundai, situated in the PyeongChang Winter Olympic Park next to the main stadium. Our concept was about exploring the beauty of Hydrogen, the new fuel for Hyundai cars. We wanted people to experience hydrogen in the form of stars and in water droplets as both are reserves for the element Hydrogen.

- Hyundai Pavilion by Asif Khan at the PyeongChang 2018 Winter Olympics. Photography by Luke Hayes.

ID: And how did you do that?

AK: Our design nestled amongst the winter snow was the blackest building ever built, a 130-by-130-foot form dotted with starlight. Each of the four façades were parabolic, concave, and covered with a special nano coating called Vantablack VBX2, which was able to absorb over 99 percent of the daylight hitting the building. The result meant that building was blacker than any other building on Earth. Upon this black surface, we embedded a field of several thousand LED lights projecting at different distances to create the sensation—during daylight—of moving past stars suspended in outer space. Inside the building, visitors encountered a white space which contained a vast single surface with 5,000 feet of super hydrophobic water channels across it, each carefully designed to create wonderful high-speed tracks for water droplets to move along, like vehicles moving with incredible precision along routes in a future city. I could, and did, stare at the facade for hours. It was something remarkable, like a window to outer space.

- Inside the Hyundai Pavilion by Asif Khan at the PyeongChang 2018 Winter Olympics. Photography by Luke Hayes.

ID: How does the Expo’s design speak to where design is headed in the future?

AK: I like to use my projects to explore what the future of our cities and lives could be, and then build these ideas, so we can test the possibilities for ourselves. At the same time, I am very focused on basic human experiences and finding ways to connect our rapidly changing world to the primary sensations that make us human. I believe the Expo Entry Portals represent a future form of architecture that embraces and explores what sense of place could mean. I believe the thinking, engineering, and technology used will inform the direction we are moving towards. In the future we must not forget sense of place. Landscapes are different all over the Earth and I think humans need places to be unique, too, and to have meaning. It’s easy to copy and paste, and too many offices and clients do this. We must make the effort now for the future world to be a wonderful place.

ID: What else are you working on right now?

AK: The studio is working on several interesting projects across the globe, including the Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture in Almaty, Kazakhstan, which will open in 2022. It is a new contemporary art museum housed in a huge Soviet 1960s cinema. Another cultural commission we have just begun on site is a new Museum of Manuscripts and Contemporary Middle Eastern Art in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates. We are also designing the 258,000-square-foot new Museum of London with Stanton Williams and Julian Harrap. We’re all four years in and the project is scheduled to open in 2024. To have a chance to create a new museum for London, in London, about London, at this moment in time is incredibly exciting for us.

- The Tempietto nel Bosco installation by Asif Khan during Milan Design Week 2014. Photography by Luke Hayes.

ID: How did you decide to become a designer?

AK: I don’t think I ever actually decided, but maybe some experiences conspired to set me in the right direction. My late aunt, Naseem Manji, had impeccable modern taste. Her house had a set of nesting tables which I encountered regularly in childhood. Only in my twenties, when they were long lost, did I realize the impression those little tables had on me. I sought them out and discovered they were designed by Poul Kjærholm the 1950s, and hers were an original set. Their white Plexiglass surface sat—but was not fixed—onto cubic steel frames, welded invisibly. These simple almost transparent microstructures stuck in my mind as a remarkable coincidence of absolute ordinariness and perfection. While I spent my childhood making and deconstructing things at home, building in the garden, experimenting with computers, sound, and video, the perfection of Kjærholm’s design probably set an aesthetic benchmark for me.

- The U.K. Pavilion by Asif Khan at Astana Expo 2017. Photography by Luke Hayes.

ID: Which of your projects has most shaped how you view your own work and the world at large?

AK: The Expo 2020 Dubai project has deeply changed me. I think it’s the closest I have come to expressing who I am as a designer. The project is a reflection on my own cultural heritage, which is why it’s been particularly transformative. Earlier projects such as my first commission at West Beach, Littlehampton, for a café for the local community, have also been similarly impactful. It taught me one of the biggest lessons of my career: the responsibility you have to the people of a place.

Read next: 10 Product Highlights from Dubai’s Downtown Design 2019