10 Questions With… Barber Osgerby

Thanks to a mix of kismet and pure talent, the meteoric rise of design darlings Edward Barber and Jay Osgerby began when they met during their first week as architecture students at London’s legendary Royal College of Art. Collaborating even during school, the designers went on to establish their London studio Barber Osgerby in 1996 shortly after graduating. By 1998 were already named Designers of the Year at New York’s International Contemporary Furniture Fair (ICFF).

Today, after 30 years spent working together, the duo’s camaraderie persists—they tend even to finish one another’s sentences. And to the undeniable advantage of the design world and quotidian human experience, Barber and Osgerby remain steadfast in their dedication to ingenuity and innovation. Although they work on roughly 50 projects simultaneously, the designers call themselves “pretty fussy” and admit to turning away any brief that doesn’t allow them to “innovate.” Yet, hearing the pair discuss innovation isn’t trite. In 2021, they express unwavering confidence in the future of product design, even as the global pandemic has rattled the architecture and interior design sector over the past 19 months or so.

Here, as we discuss some of their most archetypal projects and anniversaries, the Barber Osgerby duo reminds us that good design will always be relevant (hello Tip Ton chair), there is hope in the uncertainty of the future (who could have predicted their Olympic Torch assignment), and that some of the best ideas might arrive 20 years early (meet their recent Salone del Mobile launch, Paddle). Editor’s note: This conversation has been edited for brevity.

Interior Design: How did the two of you decide to launch a design practice together in 1996—what gave you the sense that you could work so well together?

Edward Barber: It was destiny! We ended up sitting next to each other at the Royal College of Art on the first day. That’s what brought us together. We started working together professionally less than a year after college. We did various things, then we came together to do a restaurant in South Kensington.

Jay Osgerby: Yes, we became friends first at college and fortunately got a few projects together while we were still students and started working on them. Not long after we graduated, things started to go quite well and we showed projects in New York, and we were designers of the year at ICFF, much to our surprise! That was in 1998. It was very lucky that we were even there to accept the award, because we didn’t think there was any chance that would happen. . .Things changed a bit when we met Giulio Cappellini in the early days. At that time Cappellini was really the most avant-garde and interesting collection of designers, but also of objects, furniture and product. It was this that opened our eyes to the potential of the design world outside of London.

ID: It’s the 25th anniversary of the Loop table, the first piece you ever launched together. What do you remember most about that time?

JO: Well, we designed something for one of our restaurants, and the Loop table was that piece. And we were fortunate enough to find an incredible manufacturer in London who let us prototype it, Isokon Plus, and it was that table that Cappellini saw and that really introduced us to the world of design, especially Italian furniture design.

EB: We were studying architecture at college, and we set out with a small architectural practice doing residential conversions and restaurants and stuff, we weren’t doing any furniture at this point. The first piece we did was really the Loop table. It was a twist of fate that it was quite good and got sponsored and ended up putting us into the Italian furniture world which then went on to form most of the things we’ve done since.

JO: It was one of those occasions when the stars really were aligned for us in the sense that one thing really happened after another. Having had this table made, we then did a collection with Giulio Cappellini. The Loop table was then spotted by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to put in its permanent collection, and then the V&A. Somehow we had obviously just tapped into something that was current, and it wasn’t intended to be an intellectual exercise or a revisiting of significant parts of history, or the history of plywood furniture and all of that stuff. But somehow it felt like the right thing at the right time made by the right people. We learned so much from that process and went on to create introductions with all sorts of different manufacturers and people.

ID: It’s also the 10th anniversary of the Tip Ton chair, which you designed for Vitra as the first solid plastic chair with a forward-tilt action. Do you often go into the design process seeking to break boundaries like that?

EB: We always aim innovate, whatever we do. So even the Loop table in a sense was an innovation to us at the time. Not in terms of its material, but in terms of its architecture, even though now it feels very much part of that era. But with Tip Ton we didn’t set out to change the world of furniture or something, we were actually working off a brief which was to design a chair for learning, for the state school system in the UK. Through immense amounts of research that we’d conducted ourselves and research that we uncovered that was done in Scandinavia and Central Europe in the 60s, we learned that, when people can move when seated, it improves concentration because of increased blood flow. The fact that if you can tilt forward on your chair gives you a much better posture—a straighter spine. All this research led towards the Tip Ton chair; it wasn’t because we were trying to design a chair that looked different from everyone else’s.

JO: No, definitely not looks. One of the things that we always try and do, and the Tip Ton is a really good example of this, is not to design something to look different, but always to give the thing a different way of working, something that gives it another purpose. Otherwise, there’s not a great deal of point to design, is there?

ID: Does a new way of working also refer to materials? For example, with the On & On chair for Emeco, how did the desire to make a recyclable chair shape the design?

JO: Often it does.

EB: For that particular project, we were given the opportunity to work with a new material which they were still actually developing when we started the project. They said, we’ve got this new material that’s going to be endlessly recyclable. Emeco had been working with a plastics manufacturer in America to develop it, and when the On & On chair came out it was the first chair to use that plastic. The concept of the On & On chair is that the product could in fact live on and on. You could buy 100 chairs for a café or for a restaurant, and if anything got damaged or broken, you could then send it back and they could regrind that chair up to remold it and make new chairs. So in fact it has an endless cycle. And that informed how we designed the chair, because it’s stackable and you can keep stacking it round and round. So there’s a bit of poetry in both the name, the shape, and the material.

JO: Same with the Tip Ton chair. Sometimes psychology helps us update a product. The Tip Ton chair which has always been made from virgin polypropylene is now able to be made using post-consumer waste. We’re able to collect up all that stuff that would otherwise get burned or sent to landfill and actually make it into something that can last a lifetime. In a way we’re sequestering junk into pieces of beautiful furniture.

ID: You’ve recently launched the Paddle door handle for Olivari, at Salone del Mobile. For most people, it’s rare to look at a door handle and think about how beautiful it is, but this design is so sculptural. How did you achieve this?

EB: What’s really nice about this handle is, when you push down on a handle to open it, if you’ve got a large surface area like this, it’s quite soft on the hand. You don’t really grip a handle, you’re actually just pushing it down to open or pulling it shut. Here you just push down with the palm of your hand. It is a piece of sculpture in a way.

JO: It’s one of those things that you could say designed itself. It’s something that we had in sketch form for a number of years. We always wanted to realize it, but when we came back to it, it hadn’t aged in any way.

ID: Do you sense that people are currently looking for anything new or different in your designs, in the wake of COVID-19?

JO: I don’t think so, in all honesty. The way that we work on projects is so long, that we see beyond the pandemic. I know that is a strange thing to say possibly, but we’re confident certainly in product, furniture, and industrial design that life will continue. I think things are very different in architecture and interiors. I think things will change there—they already have, and they will continue to change. But certainly, in our world, it’s kind of business as usual, isn’t it?

ID: What’s been the most challenging for you during the pandemic?

EB: Travel has been pretty much impossible. Moving furniture projects on particularly without visiting manufacturers and talking with engineers and working with the teams has been very problematic. It slows down the projects. In some cases the projects are going ahead, but we’re not necessarily 100 percent confident. Projects will be coming out over the next year, where we’ll have had a lot less physical involvement than we’d have liked. But the door handle was a total pandemic project, in that the engineering and prototyping was all done during the pandemic. An object like this is very easy because you can just post it, or FedEx it, or whatever you need to do. There’s a lot of backwards and forwards and 3D printing, and that’s very easy, but when you’re working on an office system or a big sofa system, you can’t be shipping that around.

ID: What do you think is special about the Axor One collection and its expansion? How is the collection moving bathroom design into new territory?

JO: That project is perhaps a little bit like the Tip Ton. It wouldn’t have happened at all if there hadn’t been a breakthrough in technology. We were initially thinking about a collection that had such amazing control that it was maybe electronic, so that you could really control the supply of water to be completely binary—either on or off. Although that was what we wanted, we were reticent to use any form of electric interface. We were really lucky that, once we were thinking about this, Axor came up with the idea of a binary control, like a ballpoint pen that you could click on or click off, that was purely mechanical and not electric. That was the starting point for Axor One, this idea that you could control water incredibly precisely without wastage.

Also, the projects that we have done for Axor, as well as controlling water amazingly, have removed a lot of metal. On the new tap that we’ve done, the lever interaction is actually in the pipe. There’s no secondary tap part. We knew that it was a new technology, and rather than then designing a new spout to go with the new interaction, we felt it was better to rely on an archetype to integrate the technology so that it felt visually familiar to people. So that’s how it evolved. We also really like the simplicity of just having the lever straight on the pipe, because it’s never been done before and it’s a real technical achievement to do that.

ID: What’s the distinction between the initial launch and the expansion of Axor One?

EB: The taps and the showers were the second part of the project, the first part of the project was the control panel that we did a few years ago. That was also a big breakthrough because you could mechanically preset the temperature and the flow so that when you get into the shower in the morning you literally just touch the panel and you’ve already got everything coming on. And also, while we were thinking about this, because they are quite often used in hospitality, it was important that it was ADA compliant as well—so the panels are a decent size, so that you can actually turn them on and off with your elbow or your arm, both with the tap and with the control panel. So we were trying to address quite a few different things, and that’s what ended up with us designing this new archetype for the bathroom.

JO: Almost everything we’ve spoken about brings a better way of working, a better interaction, or another layer that isn’t already available—and not something that is superfluous or token, but genuinely useful. In the case of the Tip Ton chair, we have movement but without mechanism, and in the Axor project, we have a new interaction but with no wastage of water, so it’s saving metal, saving water, and joyful to use.

ID: What makes you excited to keep designing?

JO: It’s purely the opportunity to find new ways of doing stuff. When we run out of things, we’ll stop, we won’t keep going.

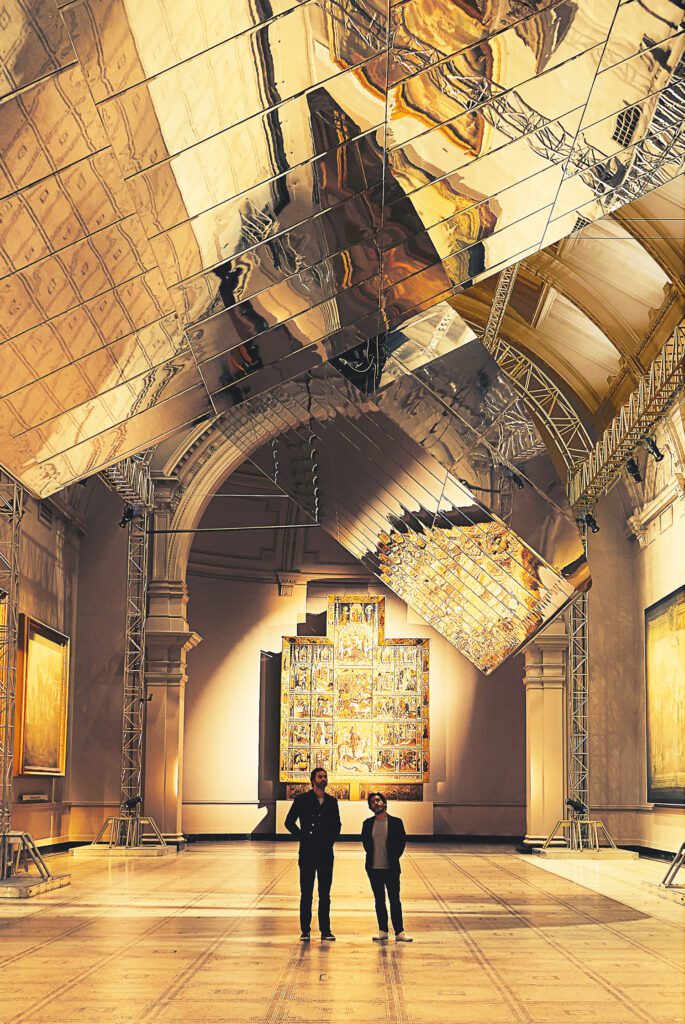

EB: It’s the opportunity to be innovative, in whatever direction that brings us—in any direction! That’s why I think over the years we’ve done so many different types of projects. We haven’t stuck with one particular area because for us that’s not enough. We’ve been in industrial design, furniture design, lighting design, installation design, we do gallery work, we’ve done architecture, ceramics, drawings… We just keep trying to find new areas that satisfy our inquisitive minds. The most fascinating projects we’ve worked on have been things that you couldn’t have predicted—things like the Tip Ton chair. We didn’t see that one coming, it came out of another conversation and suddenly we were designing it. The Olympic Torch project, we didn’t sort of say, “right, one day we’re going to design an Olympic torch.” We didn’t even know it was coming to London. And then suddenly you’re doing it! We also did a really great project with BMW which was an installation at the Victoria & Albert Museum about seven years ago. That was an incredible project, but we could never have predicted it.

more

DesignWire

10 Questions With… George Yabu And Glenn Pushelberg

The cofounders of Yabu Pushelberg keep breaking new ground, expanding into product design and art consulting with work that connects on a human level.

DesignWire

3 Queer Makers Pushing The Boundaries Of Design

Follow queer makers Adam Chau, Cynthia Ugwudike, and Leilah Babirye and discover how they are using their works to tell stories of identity and creativity.

DesignWire

10 Questions With… Liz Collins

Brooklyn-based polymath Liz Collins reflects on her evolving fiber art practice ahead of her upcoming RISD Museum retrospective and monograph.