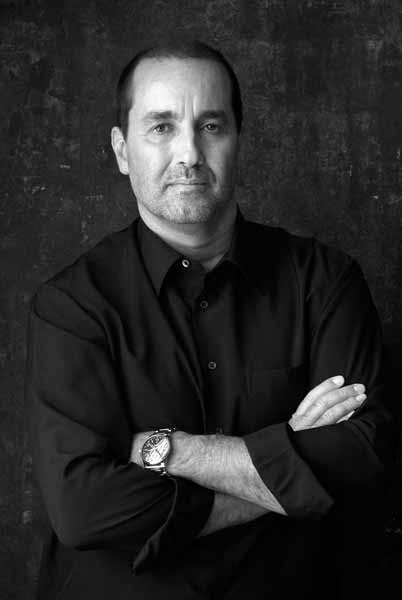

10 Questions With… Dan Meis

Newly allied with

Woods Bagot

as the firm’s global director of sport, New York transplant Dan Meis is bringing his team’s winning ways to sports franchises the world over. Previously of

Ellerbe Becket

,

NBBJ Sports and Entertainment

, and his own

MEIS Architects

, Meis is the mind behind LA’s Staples Center, Phoenix’s Dodge Theatre, Japan’s Saitama Super Arena, and Seattle’s Safeco Field, among other large-scale sports and entertainment complexes. Right now, he’s bringing a futuristic soccer stadium to Rome—a Coliseum-inspired structure for the AS Roma soccer club.

Interior Design: Dan Meis Architects was long based out of Venice, California, an area known for its freethinking design community. Now that you’ve relocated to New York for Woods Bagot, do you miss the west coast?

Dan Meis: I loved working from Venice. I loved that it is a place where there are historically no rules. A lot of architecture that influenced me came from there, too—that of Thom Mayne and Frank Gehry. The LA crowd has always thought of architecture in a different way. I got into sports design right before I moved to LA. At that time, 99 percent of sports architects were based out of Kansas City. LA allowed me to think of sports projects in new ways, without being limited by context.

There’s been a bit of an adjustment to the more corporate feeling of the design world in New York, although I did move here to partner with Woods Bagot and utilize the resources of a bigger firm. It’s a different world; my office used to be on the beach, music blaring all the time. That said there are great plusses, such as proximity to all the professional sports leagues, which are based in New York.

ID: You’re revered for your stadiums—have you always been a thinker on this level?

DM: People often think I consciously decided to set my sights on building stadiums—that I was either incredibly into sports or I really liked the building type. It’s not nearly that calculated. As a student in Colorado, I thought I’d be doing houses for people in Boulder. But the father of one of my college roommates was a Chicago developer and recruited me. I instantly fell in love with the scale of the skyscraper and proceeded to grow up professionally in the world. I have always been influenced by the impact of architecture on a skyline.

ID: But to become one of the premier stadium architects in the world is truly an unorthodox path. How’d it happen?

DM: I was working for Murphy/Jahn, which was a big deal. We’d be working on 40 different high-rise projects at a time. It was big architecture on a big scale. Then in 1992, I had an odd twist in my career. I met a woman who grew up in Kansas City and wanted to move back there, so I went with her. It was there that I stumbled into the world of sports architecture. I was not a rabid sports fan, but what really grabbed me was that stadiums were a building type getting built.

ID: So that sparked your interest. What held your interest?

DM: The opportunity to build something that had a huge impact on cities and affect people in a wide range of ways spoke to me. A stadium is very cross-cultural, after all. The wealthy VIP in a suite feels similar ownership to the cab driver in the stands. A stadium gets millions of people using it on a yearly basis, and is the embodiment of fans’ passions. Now, the challenge, I’ve since learned, is in making this big, monstrous building, rational to a city. How do we make them good urban buildings?

ID: Certainly that question is coming up quite a bit with the new stadium for the AS Roma soccer club in Rome, Italy. That is a huge undertaking. What is being asked of you, and how do you envision the project taking shape?

DM: Of course we’re dealing with thousands of years of history with this stadium, in that is has been acquired by an American owner [Jim Pallotta]. That has been a real twist for the league. It’s a history thing. Suddenly there’s an American model of ownership in Italy. Consequently, the team is playing better than they have in years. The charge for us is to create a new, state-of-the-art building that will drive revenue, yet stay grounded in the history of Rome. We did not want to create a Vegas copy of Roman architecture, but offer distinct references. For me, it was obvious that we had to consider the coliseum, which has always been the model for sports architecture, everywhere. Fan response has been great. We’ve attempted to draw upon the urban ideas of the coliseum in a very contemporary and state of the art way. People see the reference, but it is edgy.

ID: What are the challenges you are encountering?

DM: Well, we’ve all heard that Rome wasn’t built in a day. The obvious challenge is whether we can overcome the bureaucratic process and build this in an American time frame. Since we exposed the project publically, there’s been a great outpouring of support. There’s so much passion for the team and the opportunity to have this modern stadium in Italy, so I’m optimistic that we can overcome any roadblocks. Rome is the project of a lifetime.

ID: There must be a bit of an anthropological or sociological element involved when introducing a stadium to a major urban area. What does that look like for you and your team?

DM: It starts with a research project. We want to know the relationship of a stadium to the geography of a city, as well as the more social aspects. What is the cultural connection to the building? They’re the cathedrals of the day—an escape; a building type that takes you away. Our base challenge is safety and security. We have to protect fans and protect players from the fans. Beyond that we can to connect with the culture of the fan base. Needless to say, we go to a lot of games.

ID: Much has been said about this period we’ve entered, as cities grow in size and density… So much rides on the way we handle our design and architecture concerns today. What are the great opportunities for architects of this generation?

DM: Whether it’s driven by architecture or politics, I know that sustainability has to be critical. Honestly, the most sustainable thing you can do is to not build—given the resources used to build, source, and transport materials. I’ve always been disappointed by the LEED touchstone, I’ll admit. In Europe and Japan, where energy costs are high, you become sustainable very quickly because you have to be. It’s an evolution beyond where we are here. I would not want the U.S. to emulate China in any way other than how they have connected all their major cities by high-speed rail. They just did it, within a few years. The U.S. is slow to grasp what true urbanization truly means.

ID: You’re a sought after lecturer. What are some of the points you feel most strongly about conveying to students embarking on this career?

DM: It bothers me, when I’m teaching or talking at universities, that there’s not enough time spent teaching people how to communicate ideas. You’re creating a product—one that functions. A client has to hire you to do it in the first place, which is an overlooked part of the equation. It’s vital to communicate the value of what we do. I’ll see architects competing with each other without fee, which is a bit tragic.

Another thing is, I’m of that last generation of people who actually draw. Few people are learning how to sketch, and it’s becoming a lost talent. I find sketching to be a much quicker way to work through ideas, and that skill offers the opportunity to have visceral discovery.

ID: How are you inspired today?

DM: I’m always reminded, every time a new project comes my way, of how important a building will be to the people using it. Rome has been the craziest project, and I’ve had thousands of messages on my Instagram account from fans asking, “Please do this with the building; please do this.” It’s inspiring to know that there are thousands of people so hopeful and excited. I know I’m doing something important.