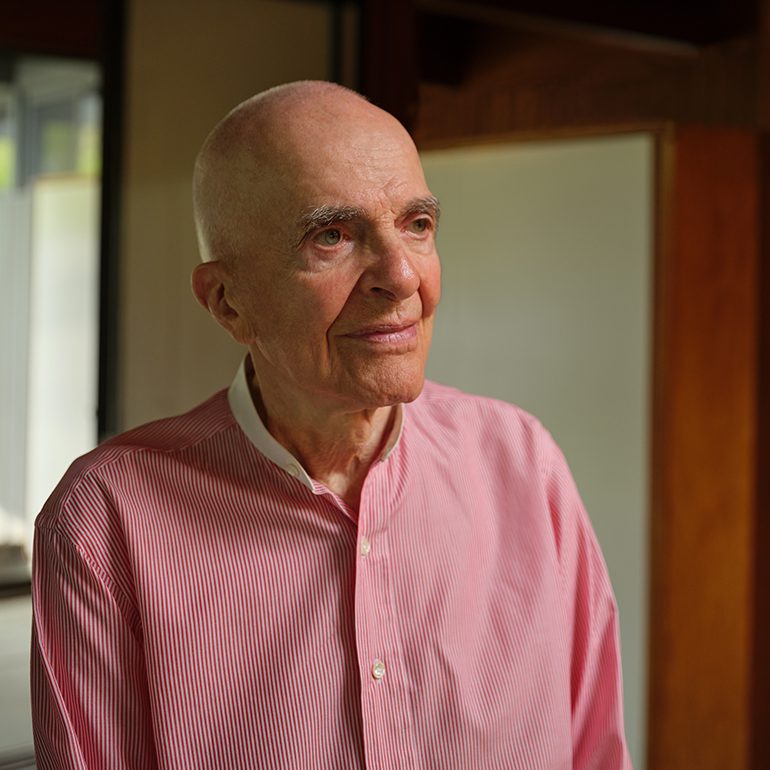

10 Questions With… Gerald Luss

Gerald Luss might not (yet) be as famous as Eero Saarinen or Charles and Ray Eames, but he might just be more influential. His commercial office spaces, designed over some 70+ years and surely encompassing tens of millions of square feet in large-scale projects for Olin Mathieson and Corning Glass, introduced the rational and modular to the American workplace. His 1959 interiors for Time-Life’s Harrison, Abramovitz & Harris-designed headquarters in Midtown, Manhattan defined the moment so effectively that “Mad Men” used them to establish its own time and place.

Gerald Luss might not (yet) be as famous as Eero Saarinen or Charles and Ray Eames, but he might just be more influential. His commercial office spaces, designed over some 70+ years and surely encompassing tens of millions of square feet in large-scale projects for Olin Mathieson and Corning Glass, introduced the rational and modular to the American workplace. His 1959 interiors for Time-Life’s Harrison, Abramovitz & Harris-designed headquarters in Midtown, Manhattan defined the moment so effectively that “Mad Men” used them to establish its own time and place.

The Time-Life building expertly integrated commissioned murals by Josef Albers and Fritz Glarner, but Luss’s unparalleled eye for embedding the artful within the practical best expressed itself in a house he built for his own family. His 1955 home in Ossining, New York equals any Modernist gem in New Canaan, Connecticut, or beyond while also remaining exactly itself: a balance of the prefab and the custom, of steel and glazing and cedar and walnut.

This summer, Object & Thing, in collaboration with galleries Blum & Poe and Mendes Wood DM, stages the Luss House with a vibrant mix of his own clocks and furniture, and work by contemporary artists who’ve made homes for themselves in his legacy. Now 94, Luss recently spoke with Interior Design, in a conversation edited and condescended for clarity, about what’s wrong in the modern workplace, the joy of an early morning phone call, and how to get an apartment in the Dakota.

Interior Design: Let’s start at the beginning: How did you first become interested in interior design?

Gerald Luss: I had been stationed in Denver during World War II, and as part of its Army Specialized Training Program I studied architecture. After the war ended, I hitchhiked from Denver to New York City and called the dean of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, where I began studying that September. But I became disenchanted over the next 18 months because the emphasis then, as it is today, is for designing from the outside in—creating the exterior and then squeezing in the way people will actually live. Anyway, I became friendly with the dean and complained to him about this. I did not understand why this rationale for architecture, which is enclosed space, envelopes of space. He said that he had a close friend who escaped from Germany during Hitler’s time and was going to start an interior architecture program at Pratt; and he said you and he speak the same language. I met him in Grand Central Station and we talked for a few hours, and then he said come assist me in developing this program, and I did and graduated in 1949.

At that time, the only type of employment opportunities for graduates was as junior draftsmen. A headhunter sent me to SOM and other major firms, and they offered me that position but I turned them down. I said, I’d rather start my own office. My headhunter gave up on me. (laughs) But then a few months later she called and said something had opened up and maybe you can do what you want at this small firm called Designs for Business. I interviewed at their 4-story walkup on 6th Avenue and 47th Street and they liked my work, but would start me as a junior designer. I said no and packed up my portfolio and left. But the next day there was a call asking me to come back, and the president offered me a junior draftsman position and I packed up my portfolio and walked out. Then I said to myself, let’s try something else: I walked in and said I’ll accept the position for two weeks and if by then I have not revised your thinking to accept me as a designer, that will have been two weeks’ investment of your dollars and my time. He laughed and said okay.

ID: How did the Time-Life project come about?

GL: After approximately 17 years with Designs for Business, I started my own firm. One morning, the phone rang. That’s the way projects always happened, early morning phone calls. At 8 a.m., Henry Luce III was on the line saying he’d been referred to us by Architectural Forum, which was a Time-Life publication, as the designer for 350,000 square feet they were leasing in Rockefeller Center. I said, ‘Yes, that would be something I’d be interested in talking about. When do you want to do that?’ And he said: ‘right now, we’re downstairs.’ (laughs) That was probably 50 times the scale of projects we’d done before, but that didn’t concern me because the formulation of a project, whether it’s a closet or a building, is exactly the same. You have to understand the requirements and get under the skin of the design. You have to understand what it is that they need for their way of life and work. I never put pencil to paper until I have that sense of fully understanding. So Henry Luce and a group of four representatives of the magazines sat down across the table. He said, ‘what we need you to know is that each magazine has to have their own identity, their own heartbeat, do you feel equipped to do that?’ I said, ‘if I didn’t, I shouldn’t be in this profession.’ (laughs) We got started on a handshake.

ID: Did they immediately agree with your notion of how to divide the space?

GL: The Plenum System developed from the space needs necessary for the 1,500 research people at Time-Life, along with the editorial, management, and creative people. But the research space needed about 75 square feet per person. Within the horrific column configuration of the building, I found a common denominator would be a 3×4 module. The average lifespan of a partition was about six months—about the time when a group would gather to begin formulating an article that would publish six months later. Their needs might be diametrically opposed to the needs of the previous group occupying that same space. And so fixed walls with wood studs were constantly being demolished. The cost was absolutely astounding, but they were successful and could absorb it. But it led me to think about a module developed toward the ceiling as a cube of space, with all the elements the contemporary office needed. Compared to the cost of the demolish program, Luce said it made sense.

And it followed that the same thinking could be applied to the furnishings of those 1,500-2,000 spaces, in that their furniture could either be picked up and moved with the occupants, or stay. So that led to a system of modular furniture forms that ended up in the Time-Life offices and on the sets of “Mad Men.”

ID: That show seemed to get a lot of the design details of the period just right. But what do you think we’re getting wrong in office space now?

GL: Do you have three hours? (laughs) The major one, which never appeared in any of my developed projects because I don’t believe in it, is the open plan concept. It’s antithetical to how people really work at their best. Anything throughout history that has been creative and had a major impact on how people are able to live their lives, whether in an office or a gasoline station or their home, relies on the ability in an environment to think through a given problem in a logical way. I don’t think open plans, with people running all around and sitting down together in the open space and causing acoustical interruptions for people in the adjacent spaces—I don’t think that is in any way contributing to that concept of how thinking best develops.

ID: Had you already designed your house in Ossining at this time?

GL: Yes. I’d bought five acres in 1952, sited on hillside from which, on a clear day, you could see three states. Since my youth, at seven or eight years old, I looked forward to each Saturday because I would take a sketch pad and some pencils and go into the foothills of the Adirondack Mountains where I grew up. So when I acquired the land, the first thing I did was build a 12-by-18-foot tree house out of Unistrut right in the heart of the site. Every night after work I would come out, and on the weekends I would live in it, just breathing in and infusing my mentality with nature. The house was just screens on four sides, up on stilts among the foliage. It’s really the same as the laminated posts and beams I developed for the house. After the war, many materials had been developed to replace those used in the war, such as laminated wood and flexicor slabs which were never used in residential structures. It struck me that they were perfect. I called manufacturers and told them what I was trying to achieve; they gave me unbelievable price concessions because they thought I might introduce concepts they’d profit from over the years. Once it was completed, I invited the Time-Life people up for an early project meeting so they could see how my mind works as an architect. I had a large studio on the lower level, with those amazing views of three different states, and a ping-pong table for a desk. That was the beginning of weekly project meetings for the next three years.

ID: At the moment it’s a sort of museum. Does it look different to you now?

GL: The design concept I developed for the house is perfect for the use of the exhibition because the spaces essentially become easels to display this diverse group of artists. A background is not more important than the art. The interior spaces and my minimalist preferences do not compete with the art. The art is the major star. Human beings should be the major stars in any enclosure. It should be habitation, not the architect’s ego, that dominates the room.

ID: Have your residences for other people followed similar precepts?

GL: I designed an apartment on the penthouse of the UN Plaza high-rise, and it’s one of the most elegant I’ve ever done. Essentially, it’s composed of two materials: marble that grows out of the floor and into the walls, and plaster for the ceilings. They are two materials wedded to each other to form the entire space.

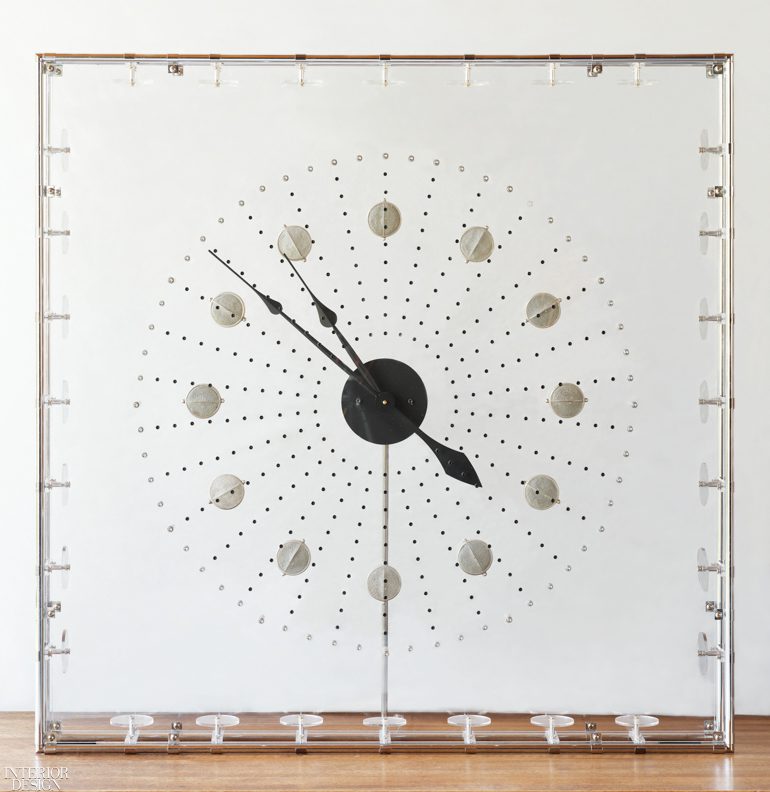

ID: How did you begin making clocks?

GL: They happened as a result of a series of travels in 1983 and 1984 across the U.S., Bogota, Paris, Italy, and then London. Of the 7,117 different languages, the over 150 countries throughout the world, the thousands and thousands of cultures, there was a single common denominator that infused all their lives: 24-hour timekeeping. With that constriction in terms of hours and times, the design of the faceplate of time pieces could reflect all those cultures and differences. So I acquired an old opera house with a 1,000-square-foot space on the lower level, turned it into a design room, and started to experiment with clockfaces and clocks. It’s led to a lot of fun over the years.

ID: And now you live with your wife and work in New York City’s coveted Dakota building. How on earth did you manage to secure an apartment there?

GL: When I was 13, my sister woke me up and took me from our home in Gloversville, New York, 200 miles away to Times Square. She knew that I’d intended to be an architect since I was eight. She asked me what were my aims when I graduated and I said, mine are twofold: I’m going to practice architecture and I’m going to get out of Gloversville. (laughs) So my sister, knowing both of those predilections, at the end of this day in New York, 4:30 in the afternoon or so, took me to Central Park. She pointed at the Dakota and said, that is perhaps the most beautiful building you will ever see, and it’s breaking my heart. And I said to her: one day I will live there.

Spaces are never available. Everyone who lives here has a friend or relatives who are in line to buy their space if they ever sell. But one morning, I got a call from a real estate agent I’d become friends with, who’d put me in a beautiful space on 5th Avenue overlooking the reservoir. He said, look, there’s a space that’s going to become available in the Dakota and it may be gone before we even place an offer, but I wanted you to know so you don’t hear that I had brokered a sale. I asked to see it and he said you’re wasting your time, it hasn’t even come on the market. I said, okay, I’d like to see it. So we met there at 11 a.m. and I walked through the apartment and looked out the window at the abundance, the profusion of nature in Central Park, and I said I want to acquire it. Go to the current owner and say you have a purchaser who’s willing to pay cash and won’t take a mortgage, which is one of the things the board of directors don’t want, and he’s willing to wait until you decide finally to move, but will buy the apartment today. (laughs) That afternoon, I got a call on the telephone, which has been the joy of my life, and the owner said yes. That was a little over 30 years ago. We’ve made the place our own.

ID: You also managed to buy an office space below?

GL: It was the same kind of thing: the person had been toying with the idea of giving up the space and so my real estate friend said, ‘you want to try the same thing?’ (laughs) It’s a 750-square-foot studio with 13 foot ceilings. It was the wildest thing, a basement space in which I built my studio. The great thing is, I wake up in my apartment, I have my breakfast and what have you, and then I get in the elevator—or, if I’m feeling ambitious, walk down the 13 floors—to my studio where I work a full day. If I break for lunch I come back to my home for lunch. At 6 p.m., I return to my home. Not a bad commute. I can’t ever remember I awakened and wished I was doing something else.