10 Questions With… Gordon Hall

The body has long been a reference point for queer creatives. After coming of age with the aesthetic and theoretical norms of heteronormative teachings, artists and designers turn to the human form to challenge the status quo. Whether a person-length side lamp or an amorphous sculpture, the work lends itself to alternative ways of existence and visibility. Many tap bold color palettes and gender-defying cues to blur the line between the familiar and the new. Gordon Hall is an artist who flirts with the utilitarian aspect of design in their three-dimensional forms. Behind muted tones and humble forms, their sculptures contain various potentials of use and activation.

The body has long been a reference point for queer creatives. After coming of age with the aesthetic and theoretical norms of heteronormative teachings, artists and designers turn to the human form to challenge the status quo. Whether a person-length side lamp or an amorphous sculpture, the work lends itself to alternative ways of existence and visibility. Many tap bold color palettes and gender-defying cues to blur the line between the familiar and the new. Gordon Hall is an artist who flirts with the utilitarian aspect of design in their three-dimensional forms. Behind muted tones and humble forms, their sculptures contain various potentials of use and activation.

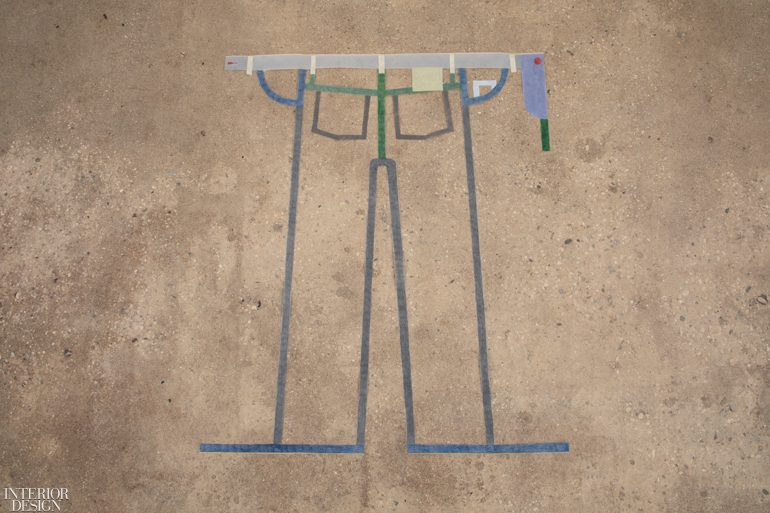

The New York-based artist’s most recent exhibition, END OF DAY, at Chelsea’s HESSE FLATOW gallery last month featured an array of standing, or wall-leaning sculptures, which could also function as stools, chairs, and ladders. “I find sculpture to be a perfect arena in which to work out [queer] ideas,” Hall tells Interior Design. “I think that sculpture has the power to teach us new ways to see, and so I make my objects with the hope that they will complicate our conventional ways of reading bodies.” A U-shaped small scale concrete sculpture suggested its potential function as a stool, or the show’s titular piece was a poplar coat rack, which reminisced a human silhouette, completely covered with steel nails.

In a dark corner, Hall projected a photograph of the artist Narcissa Niblack Thorne’s miniature interior of an art-filled Modernist apartment, California Hallway (1940), on view at Art Institute of Chicago. Disinterested in Modernist movement, Thorne had mastered creating painstakingly exact minuscule replicas of Classical interiors, and for a one-off exploration of her time’s contemporary trend, she had commissioned Modernist painter Fernand Léger and potter Gertrud Natzler to create tiny versions of their works.

Here, Hall shares with Interior Design their approach to the art of sculpture and the many uses of each piece, as well as how queerness helps them refuse categorization.

Interior Design: Let’s start with your process of making the sculptures. Do you create them with their potential uses in mind?

Gordon Hall: Quite the opposite—I try not to imagine what I might use them for while I am making them. I know there might be a use, but I don’t want to know what it is until it is finished and I can find out from the object what should happen with it. Once it is done, I watch it and listen to it to find out what it wants me to do with it.

ID: How about the performative element of your objects, particularly those in your HESSE FLATOW show? You previously activated your sculptures yourself or through other performers; what kind of similarity do you see between activation through use and performance?

GH: When I make performances that use my sculptures, I think of them as just one possible use for these objects. If people live with them—spending time with them in everyday life—I am sure they will find other uses for them, which is beautiful to me. In this sense, I never think of them as completely finished, because there are always new ways that they might live.

ID: Do you think about both artistic or utilitarian aspects of your sculptures before starting them? Do these aspects feed or challenge one another?

GH: I don’t make a big distinction between artistic and utilitarian while I am making my work. Or, I am always curious what happens when I confuse the two—a chair that doesn’t have a purpose because it’s a sculpture or a sculpture that has a purpose as a chair. There are so many different ways for objects to be useful or useless, and my work questions these definitions.

ID: When we talk about “queering” either a space or object, we refer to subverting its primary function. Queer in this case is about challenging (re)productivity and the mainstream approach. How does this notion of queerness influence your approach to object making?

GH: I think of queerness as a rejection of normative definitions of what bodies can be and what they should do. Queerness is a practice of making the fewest possible assumptions about our own and one another’s bodies. This approach of course stems from a lived need to redefine gender and sexuality, but I think it can extend into many other areas, such as how we think about race and disability, any area where we might act like we know what other people’s bodies are and what they mean.

ID: The works at HESSE FLATOW refer to the body with both their corporal elements and absence. As a sculptor, how does the body inform your work?

GH: I came to sculpture through being a dancer, and this training shaped me such that bodies are at the center of everything I do. I always think about objects in terms of how a body might experience them. My excitement about furniture stems from this as well, because furniture always suggests or conjures bodies, even when none are present.

ID: The objects flirt between figuration and abstraction—their reference to certain objects are almost recognizable, but that familiarity is slippery. How could you explain this duality through the lens of a queer aesthetic?

GH: That’s exactly right—I try to make objects that are a this, and a this, and a this, never definitively settling on one identity. Or I make things that at first seem like something recognizable, but upon closer inspection are also not that, or more than that, or off in some unexpected way. For me abstraction has been a tool to imagine a future world that is different than the one we live in now. I’m also very interested in how abstract and recognizable objects can coexist in an exhibition—how mixing them together changes how we look at each. I try to make every show have a balance of identifiable and non-identifiable objects.

ID: The show’s titular piece, END OF DAY, is inviting as well as ghostly. Could you explain your decision to cover the hanger with nails?

GH: The idea to cover the clothes valet in nails came from noticing the way nails look in old wood floors—shiny from being rubbed by everyone’s feet over the years. I wanted to turn this into a form of decoration, but also an armor, like chain-mail, or studs, or scales.

ID: While sculptures’ references to objects are universal, Hovering Dot instantly reminded me of a Roomba, which, in comparison to other referenced objects, is very high-tech and sort of unexpected. Could you talk about your method of finding inspiration in the world outside?

GH: A Roomba! Other people see a plant stand, or a tray, or a hovering black dot. All are fine with me!

ID: Five Part Bench is as mysterious as it’s inviting. How do you “build” the visual and narrative layers of each object?

GH: I try to draw on different aspects of the designed world and combine them in engaging and unpredictable ways. In Five-Part Bench, the top is drawn from contemporary public benches that are designed with lumps on them to prevent sleeping or designate where people should sit, while the grey columns are a combination of Grecian and Brutalist design. And the cast concrete fabric was inspired by the tradition of carving wood or stone to resemble draped cloth, inspired by the carved dress on a 14th century oak sculpture at the Met Cloisters. I plan the work out in advance, but if once I make it I look at it and feel in my gut that it isn’t right, then I throw it away and start over. I can never really know if something works until it exists.

ID: How do the future lives of your works influence your methods of making them? They can continue their lives at collectors’ homes, institutions’ galleries, warehouses, or other environments. Are you conscious about this ambiguity?

GH: I make all my sculptures with the hope that they will live many different lives without me. I made them, but I don’t want to limit what they can do out in the world. Sculptures aren’t meant to be wrapped up in storage.