10 Questions With… Jonathan Olivares

Cerebral, unshowy, smart design. That’s Los Angeles–based industrial designer Jonathan Olivares all over. Born in Boston in 1981, he attended Pratt Institute before taking on a postgraduate apprenticeship with Konstantin Grcic and establishing his own practice, Jonathan Olivares Design Research, in 2006. He’s been heralded as an emerging leader of contemporary American industrial design—no faint praise—and has collaborated with design powerhouses such as Jasper Morrison, Vitra, Nike, Knoll, and Kvadrat. His multi-tasking storage unit Smith, which can hang off a desk or sit on the floor as a stool or table, won Italy’s prestigious Compasso d’Oro. More of his furniture—usually spare and formally rigorous, often concerned with high-tech manufacturing processes—can be found in the permanent design collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Cerebral, unshowy, smart design. That’s Los Angeles–based industrial designer Jonathan Olivares all over. Born in Boston in 1981, he attended Pratt Institute before taking on a postgraduate apprenticeship with Konstantin Grcic and establishing his own practice, Jonathan Olivares Design Research, in 2006. He’s been heralded as an emerging leader of contemporary American industrial design—no faint praise—and has collaborated with design powerhouses such as Jasper Morrison, Vitra, Nike, Knoll, and Kvadrat. His multi-tasking storage unit Smith, which can hang off a desk or sit on the floor as a stool or table, won Italy’s prestigious Compasso d’Oro. More of his furniture—usually spare and formally rigorous, often concerned with high-tech manufacturing processes—can be found in the permanent design collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

A prolific essayist and deep-dive researcher, he spent two years traveling the world for Knoll researching the history of the office chair, which became the book A Taxonomy of Office Chairs, published in 2011. (He’s currently at work on a sequel.) On the day of launching Twill Weave, a textile range with Danish manufacturer Kvadrat (his first foray into fabrics), he gives us the scoop on the importance of humor, why nothing is useless, and why he has the smallest phone possible.

Interior Design: You recently collaborated with Kvadrat on Twill Weave, a wool fabric collection that launches today. What’s the story?

Jonathan Olivares: A daybed I made for Kvadrat in 2016 started this whole project. It was fabricated from carbon fiber twill weave: an incredibly strong woven, almost fabric-thin form of carbon fiber used for sailing masts. I wanted a textile to cushion the seat, in the same gray and twill weave structure of the carbon fiber base. The idea for a full twill weave collection working with colors taken from other natural minerals and pigments grew from there.

The great thing is I can look at the colors objectively and say that they’re really beautiful because I had almost nothing to do with them! I just set up the parameters that would choose them. The process began with visiting the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies at the Harvard Art Museum, where I asked the center director, Narayan Khandekar, if he could help me isolate 30 or 40 minerals that were used as artists’ pigments. With so much human and industrial meddling in the colors available to us today, I was interested in peeling back the layers of intervention. Looking at the rocks at the library—azurite, chromite, indigo—I was viewing unprocessed color. Then it was about photographing and selecting colors from within the mineral, translating that to two-dimensional swatches, and comparing the color prints to the original mineral until we felt we had of achieved a level of accuracy.

ID: You’ve said you see innovation as a dangerous term. Does that relate to this collection?

JO: Eames said, “Innovate as a last resort.” Innovation is a dangerous term for a few reasons, one being that it is overused in our culture so it has lost its meaning. I think if you start out saying, “I’m going to innovate,” that’s already not the right way to begin. The best projects are not necessarily innovative. I’m amazed that we got the name Twill Weave for the Kvadrat range. That’s the second oldest textile in the history of humanity. The colors are not new either, they come from these great pigments from the earth. In a way, there’s absolutely nothing new about this textile! Yet I think we did a good job.

ID: Is it more about iteration then?

JO: Yeah, it’s like baby steps. In furniture or in design, improving something happens through the generations. Generation upon generation, people add, subtract, and modify. And every once in a while, somebody figures out a better way to do it than it was done before. Whoever invented the nail, that was innovative because Western furniture is based entirely on nails and hardware. Eastern furniture was all joints and glue. That is a real innovation.

ID: What is the most important thing to you when you design?

JO: I would say, number one, that it’s a learning experience. If it’s not a learning experience, then I don’t gain anything from it, and neither will the person who ultimately takes it home.

ID: You did a year-long postgraduate apprenticeship with Konstantin Grcic after school. Any important lessons learned?

JO: I learned about great music. Happy Mondays, Elvis Costello. I knew David Bowie, but not the way he knew Bowie. But also: work ethic, rigor. I don’t think I really understood quite how much pleasure could be derived from work before that.

ID: Tell us about the exhibit you mounted on useless objects.

JO: I did an exhibition called “Useless: An Exploded View” for a biennial in Lisbon themed around the idea of uselessness. What does useless mean when it comes to products? In the end, the conclusion was that nothing was truly, entirely useless. Everything has a purpose to someone. But we had really funny things. We had a TV with Larry David in Curb Your Enthusiasm taking apart some packaging of an electronic product; he can’t get it open and he freaks out and just takes a knife and starts stabbing it. Then next to that we had CCTV footage from a local equivalent to Walmart, where you could see the aisles of package- protected products. The store is where the purpose of this extremely overprotective packaging starts. And it’s useful there. But it’s entirely useless when you get it home. But then it’s also useful because it actually produces this amazing level of humor. So it was about unpeeling the layers of use. That was a fun project. Humor in general is important to me, I try to bring that to my designs. It’s one of those fundamental bonds between people.

ID: Do you have a first memory of design?

JO: I built skateboard ramps for myself when I was an adolescent. My family always reminds me that I was really into tools as a kid. I guess you could say that tools are associated with design. Apparently, I went to work on my grandfather’s car and half destroyed it.

ID: A natural progression to being interested in tools and parts can be seen in your book, A Taxonomy of Office Chairs. Do you think you’d ever do a follow-up, and if so, what object?

JO: I’m working right now on a book that looks at the evolution of the floor plan of the office. It’s interesting to study design through different scales. The chair book is really not about chairs. It’s about chair components. You zoom into details. Now I’m zooming out.

I’m looking at things like typist pools. That role doesn’t exist anymore. You used to look at floor plans and offices from the ’70s and the ’60s and you’d see a huge area that was designated for people who were typing. Now that’s replaced with public spaces like cafes and library environments and company restaurants. Work has really changed dramatically in the last 50 years. This book traces the evolution of the office since the birth of the Internet. It’s really looking at how office typologies have changed because of communication.

ID: Speaking of the Internet, what do you see as the role of materiality in this highly digital age?

JO: Digital, to me, is just another tool. You look at the Design Research building in Cambridge by Benjamin Thompson and the lines on the concrete are not straight. I would be willing to bet that it’s because they didn’t have computer numeric control or CNC for their formwork. And now, you have factories that do CNC work to a very high degree of precision. Everybody associates digital with really complex forms. But it’s actually best for straight lines.

Digital is also great in terms of how we work. I have no physical office. I work entirely off of a Dropbox account with a team who are spread throughout the world.

So it affects how we work. I think for some people it affects what they make. For me, I’m much more physical. Even for the Kvardat collection, aside from the fact that I used a digital camera to photograph the colors, it was all quite hands-on. Touching real minerals—I think that’s important. I actually don’t like spending time on the computer. I hate computers. I have the smallest phone and the smallest computer because it encourages me to spend less time on them.

ID: What’s next for you?

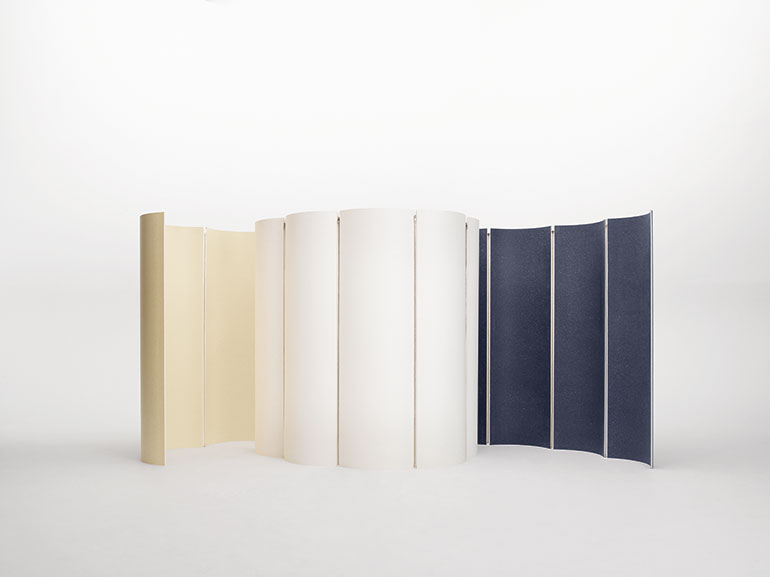

JO: I’m doing an installation in Milan for Kvadrat’s Really, which is an initiative they started in 2017 to upcycle textiles at the very end of their life cycle. Really makes rigid textile boards out of old hotel blankets and towels. I figured out an elegant way to bend this material and made a spatial divider from it.

I’m also working on an exciting project for Brujas, which is a Bronx women’s skateboarding crew. They’re an activist group who promote women’s rights, LGBT rights, immigrant rights. They will be doing a three-week residency and I’ll be designing the space, including a skateboard ramp. Skate ramps are usually handmade made by skaters, which I have a great deal of respect for because it gives skaters a job, an avenue that’s connected to their passion, and I wouldn’t want to mess with that. But as an industrial designer who works with high-tech factories, if I’m going to build a ramp, I’m going to build it with state-of-the-art production techniques. So, we’re using glass fiber–reinforced concrete, colored millennial pink.