10 Questions With… Jovencio de la Paz

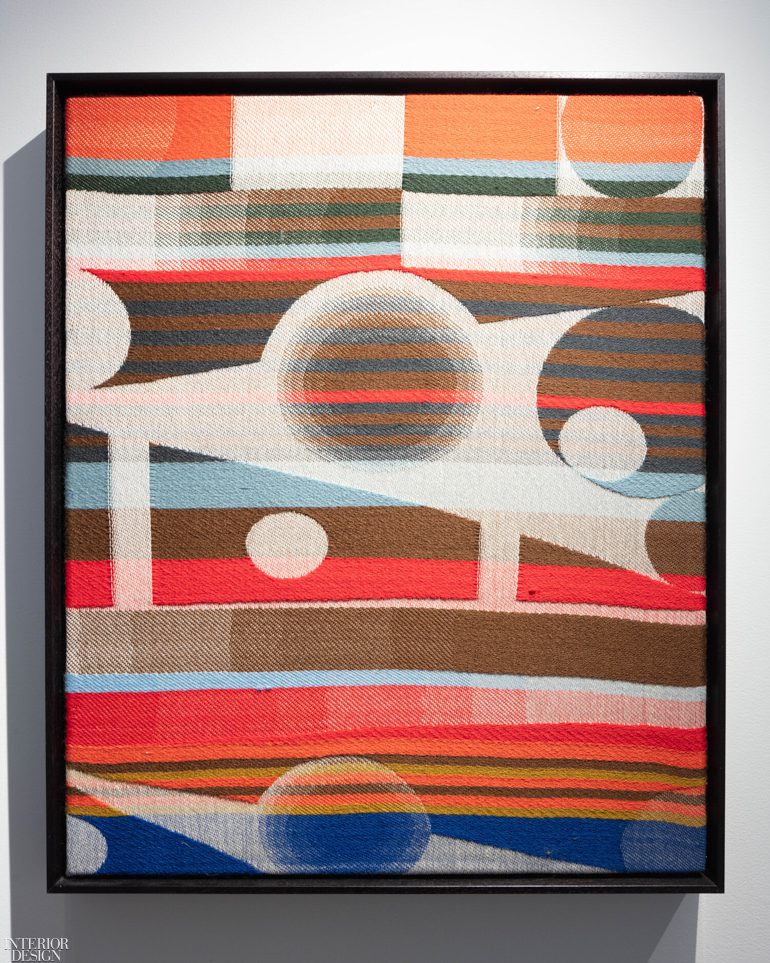

Jovencio de la Paz is an Oregon-based weaving artist whose textile paintings stem from a collaboration between the digital and the manual. The artist uses the Thread Controller software to create the patterns and later transfers them onto a loom. “I create 75% of my work on the computer with my cats on my side,” they say from a studio that overlooks Northwest’s lush nature.

Jovencio de la Paz is an Oregon-based weaving artist whose textile paintings stem from a collaboration between the digital and the manual. The artist uses the Thread Controller software to create the patterns and later transfers them onto a loom. “I create 75% of my work on the computer with my cats on my side,” they say from a studio that overlooks Northwest’s lush nature.

Between teaching at the University of Oregon and exhibiting their work at galleries and museums, de la Paz has crafted a unique weaving technique which not only includes hacking the TC2 software but also embraces the occasional glitches. Besides exhibiting in Tribeca gallery R & Company’s group exhibition OBJECTS: USA 2020, de la Paz is also in the Cranbrook Art Museum survey exhibition With Eyes Opened, which presents works by the school’s alumni since 1932.

Here, de la Paz shares with Interior Design thoughts on weaving the glitch and finding textile inspiration in computer coding.

Interior Design: Your process has such an interesting duality between the physical and digital. Could you talk about your initial attempt to craft this process?

Jovencio de la Paz: I went to undergrad in the School of the Art Institute of Chicago to become a painter. I was politically active and interested in identity, but that conversation was not really supported in the department. This was the era of “zombie formalism” in painting and I eventually shut down. I desperately asked the faculty for advice on what to paint and I was recommended the textile department. The history of craft then opened so much space about the history of marginalized communities, especially women and queer people of color. This was just when the school had acquired the first version of the Thread Controller software.

When I can weave any image for the graphic, the question then becomes about what to weave and what to represent. I was very interested in conceptual art, especially language-based Fluxus scores. In this regard, so much of my work is actually about writing an instruction or coding. I realized I could raise my two fundamental issues through this work. I can talk about marginalized identities with the language of conceptual art. Over the years, I figured I should also learn how to program. Luckily, I have lots of great collaborators and friends who are programmers. Watching them work is like watching craftspeople. The dexterity of the hands and the coordination over the keyboard is similar to playing a piano. For me, weaving and coding have a very natural relationship

ID: Let’s talk about incorporating software hacking into weaving. Technology represents productivity and solutions, but through hacking you interrupt this linear trajectory. Do you consider this a gesture related to queerness?

JP: Absolutely. I see the digital realm as a space of potential and efficiency yet with hard edges of binary distinctions. I also think of it as a place of ambiguity—of ghosts in the machine. Hacking breaks those expectations of rigid binary systems, and this definitely has a queer personality. Many queer theorists have described this, as well. Coming from textile with a very hands-on training, I think queer[ness] occupies the territory of punk culture and other subcultures in which you make do and figure your way around available materials.

ID: Technology has an ambiguous aspect which gives opportunities to queer people for self-expression. I’m curious about your own relationship to the internet and digital platforms, such as Tumblr, Instagram or even dating apps, which may all be very inspiring for an artist.

JP: As a digital native who is also a queer person of color from rural Oregon, I can say the internet saved my life. I could not find other queer people without it. My piece in the R & Company show is inspired by the science fiction author Ursula K. Le Guin’s novel, “The Dispossessed,” and I have other works which make direct references to that canon. Growing up, I spent more time on the computer because the world itself was violent. I understand the valid criticism about screen time and how long we are on our devices. But for my own personal relationship, it remains a tool of connectivity and a place of imagination and speculation. The research to understand the history of these digital spaces has been really important to me—the history of computation, of programming, of the internet. I’ve always tried to know these spaces intimately in a material way. A lot of my ideas come from research on who invented a certain software or why they did so.

ID: How does your relationship to science inform your weaving?

JP: I recently went to a craft conference in Virginia, and the keynote speakers were set designers and prop makers for TV and film. They create special effects for shows, such as “Star Trek.” Part of their role is to speculate on how contemporary art might look in the future. I was struck by their choices for art to hang on the walls in these futuristic interiors. They chose glass art from the ‘70s, traditional African objects, or pre-Columbian weavings. I see this as a dystopian warning about how colonialism persists. This is a future in which the ownership of Peruvian textiles or African masks is still in certain hands. As a queer person of color from an immigrant family, I ask: Who is imagining the future and its politics?

ID: What do you think about the gendered nature of weaving? Many queer artists and designers use craft, particularly weaving, today—we could even call this a movement.

JP: The association of weaving strictly with female labor is a North American and European concept. In India, China or Africa, textile-making is considered a masculine practice. For me, this question of gender goes back to painting. We are not painters and we need to emphasize the sculptural aspect of textile and the bodily reality of the cloth. I want to demand the real estate on the wall. When I was a student, I felt blocked out from abstraction, but my most recent work in reality talks about it. The gender equality is in the process as well as in the history which is to be manipulated and played with by artists on the gender spectrum. A generation ago, weaving was women’s work. As of today, I see in my students and my peers [that] they are in search of what they can say through this media about gender that is unique to them but not beholden to one philosophical framework.

ID: The digital universe has also changed the way we experience queerness as physical spaces have begun to disappear. How do you see this shift from the tactile to cyber being reflected in weaving, such as the ability to create patterns on the computer?

JP: It’s exciting because the technologies we use are still very emerging. Therefore they can easily go to the direction of generic really fast. Think of early stages of 3D-printers entering people’s homes. The sculptural quality of the objects then were questionable. For me, the question is how we utilize these machines more deeply. The digital opens up opportunities to experiment with these technologies. At first, a lot of people will play with these technologies in superficial ways, but this is the best way for a technology to evolve into maturity. When my students, for example, first got their hands on the Thread Controller 2, they just wanted to weave the photographs of their dogs. This is normal with accessibility to design tools.

Until the idea transcended into further concepts, many weavers were making weavings about weaving. Domestication of technology is a democratic concept. You might be able to design the files and the patterns on your computer, but the loom itself is still quite expensive which may cost up to $80,000. It can still only be held primarily in institutions. I’ve been working with moderate to high Photoshop skills. I see a potential in making a tool which is intuitive, one that lets me draw on the computer. That eventually becomes the textile, as opposed to using a third party software.

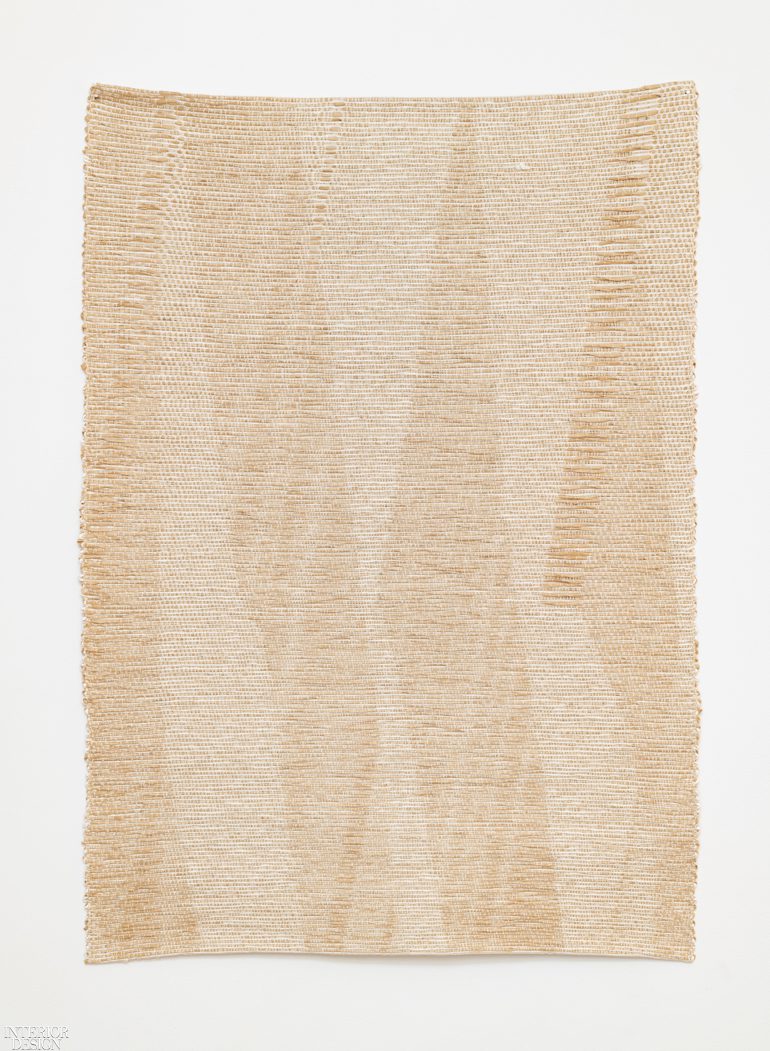

ID: Glitch is an indispensable part of technology. The imperfection is also an element in your work. I’m curious about your idea of glitch as well as omitting the idea of perfection overall to create imperfection on purpose.

JP: One of the best hacks I did with the TC2 was with a software function, which looks for your mistakes and fixes them. On the other hand, there are errors that the software can never correctly weave. Either way, the resulting textiles were bonkers to me. There are simple line drawings or fields of color. These are the proofs of the ghosts in the machine, because they reveal computational creativity of the algorithm. When we think of the computer, we still think of it as moving towards the ideal and we overlook any intercensal points.

ID: How does color inform your visual language? Could you talk about you association with colors?

JP: Color in weaving is really complex. Unlike in painting, there is not optical blending. There is the illusion of different colors, which are essentially the pixels, and they translate so beautifully to the cloth. I am a purist in many ways and I almost only use primary colors, black and white, and sometimes brown. I base my work in the native language of the screen, and for a while that meant me only working with the Indigo software. I tend to go towards the extreme and reduce to specific palettes that have some conceptual narrative.

ID: Do you find abstraction liberating for giving you opportunities for endless narratives? How do you relate to abstraction?

JP: I think about geometry, color, and composition. But above all, I actually attempt to remove myself from being the author of those decisions. I try to let the algorithm create the forms as much as possible. I’m sort of collaborating with the software to generate these abstractions. This also carries a queer element for me, because it de-emphasizes the author.

ID: Your textiles ask the viewer to get closer—whether using pixels or threads—to reveal the details. The visuals also change when you look from far. What do you think about the element of intimacy for the viewer?

JP: I love artist Ann Hamilton’s quote about how the social metaphor of cloth is very present, because you can see the collective that it produces. You can still always see the individual thread. Every textile, every woven cloth, is in fact the instruction on how to make it—it has embedded itself. If you know how to read the pattern, you also know how to make it. Threads are really linked in a way that codes are made. Nothing is obscured. Historical textiles are recreated in this way, too. The word textile and text come from the same Latin root. Intimacy for me is important. Think of the experience of reading a book in bed, that type of closeness. I want the viewer to come close a bit and see the work’s simple construction to be able to read it.