10 Questions With… Leyden Lewis

Architect, designer, fine artist, educator, art consultant, advocate for diversity and inclusion—Leyden Lewis is all that. Born and raised in Brooklyn, Lewis earned a BFA degree in architecture and environmental design from Parsons School of Design where he has been teaching as an adjunct professor since 1997, and at the New York School of Interior Design since 2016. Prior, he taught at the Fashion Institute of Technology. In 2000, he established his namesake studio, currently with four designers working remotely. He has made his mark with residences throughout New York, from the Upper East Side’s Museum Mile to Columbus Circle, U.N. Plaza, Park Slope, Williamsburg, and Prospect Park West. Leyden Lewis Design Studio has also designed model apartments and public spaces for such real estate and marketing agencies as Rose Associates, the Sunshine Group, Insignia, and The Marketing Directors. In the works is his design of The Faisal Abdel-Rahman Foundation, a school for young women, 14 to 21, in Khartoum, Sudan.

On the art front, Lewis was invited by Thelma Golden, deputy director of The Studio Museum in Harlem, to participate in Harlemworld: Metropolis as Metaphor. More recently, he produced art in another form by creating a poster for NYCxDesign, “The Black Heart Thrives,” as the Black Lives Matter movement swept across the U.S. Next up his art and design will go virtual with a concept house conceived by the Black Artists + Designers Guild, of which he is a founding and advisory board member.

Interior Design: Tell us how you are doing. How did the pandemic affect you both personally and professionally?

Leyden Lewis: I’ve lost very close family during this pandemic, and it was devastating to see how much loss directly affected my close circle of friends. That said, the silver lining is having slowed down and being offered the opportunity to refocus my attention on the things that are most important in life. Professionally, I have garnered some of the most exposure and visibility of my career. Staying creative came easily as the ideas on my studio’s back burners became the focus of my day-to-day to remain engaged. The other oasis is my association with the Black Artists + Designers Guild—our initial incubator project, Obsidian Virtual Concept House, launched January 29.

ID: You were teaching pre-pandemic. In addition to a professional roster, what did you seek to impart culturally?

LL: I don’t see culture as a separate silo of knowledge to impart upon my students. The conversations that I have maintained in my classes over the last 23 years have always been infused with expansive conversation about gender, race, geography, ethnicities, and environmental behavior. What I do maintain as a core principle is my aversion to corporate branding of trends and styles.

ID: What were your earliest memories of design growing up?

LL: My introduction to design was the Metropolitan Museum of Art kids program. What’s vivid in my memory are the hallways of Greek sculpture and artifacts.

ID: How did your family react to you, a young Black man showing interest in design?

LL: I come from a family of artists. My father is a painter, so he was happy to know that I had chosen a career in the arts.

ID: Let’s go back to your “aha” moment vis-à-vis a design career. How did you envision yourself in the design and architecture worlds?

LL: I started to become fascinated with the ability of the design of space to manage, manipulate, change, or inspire the occupant after studying architecture and design two years into my education at Parsons, The New School. Their curriculum didn’t relegate the interior of the architectural envelope to the role of interior designer. Rather, the approach to design was defined by location and function.

ID: Did the reality live up to the dream?

LL: No. That being said, life as a designer is satisfying, and I love it. But it is not what a 19-year-old would imagine a career in design.

ID: As a Black man, what are some of the challenges you face that your white peers do not? Have you plans for rectifying them at micro or macro levels?

LL: The problems I and others of my race and ethnicity face is the inherent income inequality in my profession. I have no plans to rectify this, as it is not my role. It is those individuals with the financial means to hire, collaborate, and partner with myself and other Black creatives. It is equally important to have a voice as it is to get paid. Power to affect change comes from the opportunity to do so. I intend to thrive by remaining steadfast, an active mentor, and a vocal part of this industry.

ID: Architecture and design are having a long overdue moment regarding equality and inclusivity. What’s your role? How are you collaborating with Hall of Famer Cheryl Durst? How does the art world play into your endeavors?

LL: I am an active member, mentor, and an initial founder of the Black Artists + Designers Guild. Last year, I was asked by David Sprouls, president of the New York School of Interior Design to co-chair, with Cheryl Durst and registrar Jennifer Melendez, the school’s diversity, equity, and inclusion initiative. We are developing actionable strategies to improve the environment along these ideas and with thoughtful civil dialogue. We will effect change in curriculum, faculty, hiring practices and student support.

Art is a large part of my design philosophy. I provide consultations to fellow artists and designers to curate and showcase art within their installations and spaces.

ID: Tell us about the school in Africa, its genesis, design ideas, and funding.

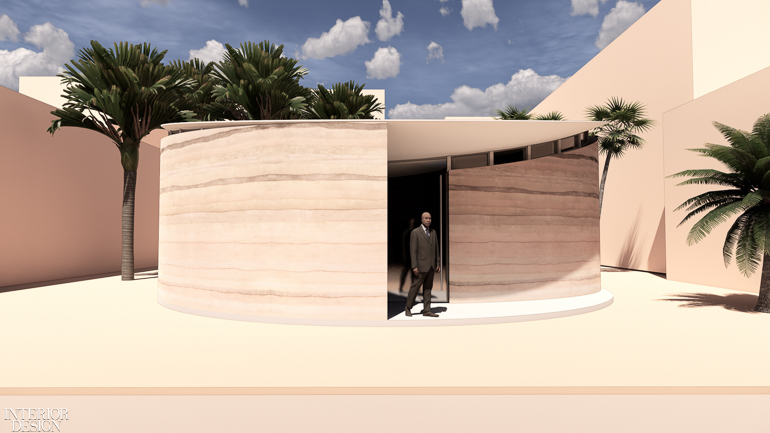

LL: I was approached to help memorialize my client’s father, a civil rights activist and lawyer, in his home city of Khartoum. The founder, Soumaya Abdel-Rahman, charged us with creating a nimble and contemporary symbol to express expansion in architectural form. The exciting project is our creative response to ancient traditions of Nubian and Islamic architecture. It’s currently awaiting funding and projected to begin construction in 2022.

ID: Come the city’s opening, what are you most looking forward to?

LL: I haven’t been to a restaurant in months and dream of getting Korean BBQ. Also, one of my favorite places to go was this little Japanese coffee shop in my neighborhood called Brooklyn Ball Factory. I am excited to re-establish my community of friends and family and look forward to sharing meals with those closest to me. However, I do not miss the rush and pressure of the city.

In honor of Black History Month, the Interior Design team is spotlighting the narratives, works, and craft traditions of Black architects, designers, and creatives. See our full coverage here.