10 Questions With… Mark Landini

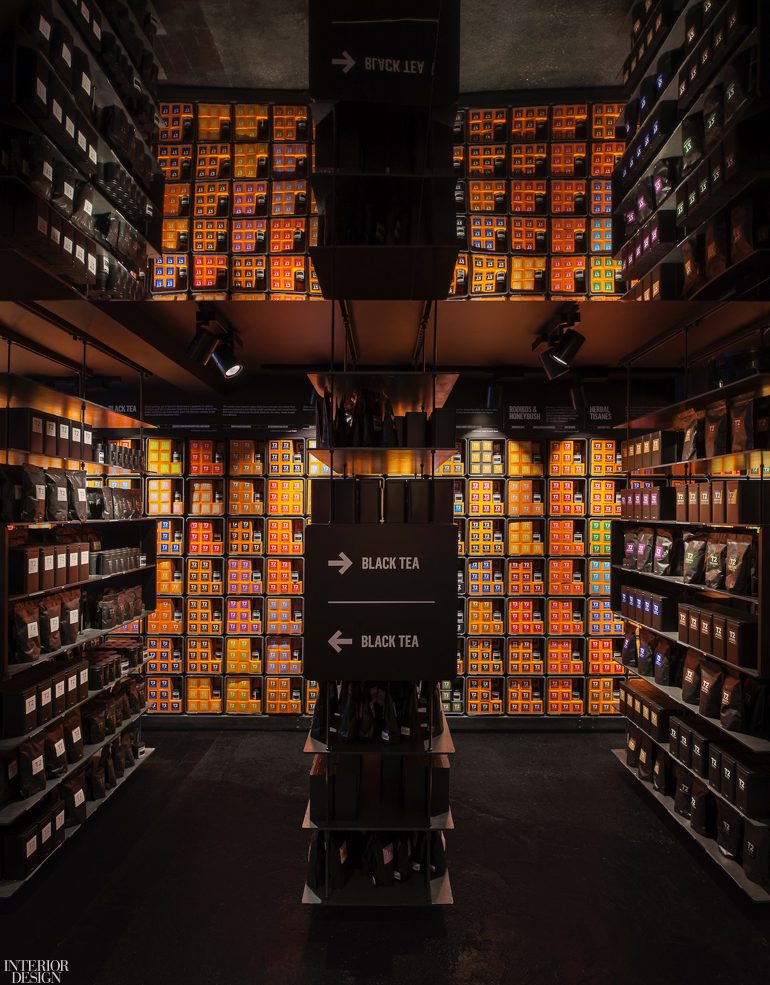

At Sydney Airport’s Terminal 1, jet-setters find a mesmerizing sight: a gigantic transparent glass box in glowing yellow that zips McDonald’s orders through an innovative vertical transportation system. Designed by Landini Associates in collaboration with fast food chain McDonald’s Australia, the sky kitchen and conveyor belt delivery system at McDonald’s Sydney International Airport, Terminal 1 quickly became a social media sensation—and is just one way Landini Associates pushes interior projects into new design territory. The firm’s client list also includes supermarket chains ALDI and Esselunga; cosmetic companies Burt’s Bees, gentSac, Jurlique, and Primera; jewelry retailer Sarah & Sebastian, Australian tea retailer T2; and hospitality giant Hilton.

“We practice what we call ‘reinventing normal,’” says Mark Landini, previously creative director of the Conran Design Group and Fitch RS before filling the same role for his namesake firm. “That is, to challenge everything, break it down, then reassemble it again in a more appropriate, more enjoyable and more efficient way. Just because something didn’t exist 10,000 days ago doesn’t mean it won’t be the market leader today—at least that’s what Amazon has taught us.”

Here Landini shares with Interior Design how he flipped the dated supermarket concept on its head, the response he sees retail design making to COVID-19, and where in Rome to find the Italian dish he’s perfectly happy to eat twice a day.

Interior Design: What was the overall design goal of McDonald’s Sydney International Airport, Terminal 1?

Mark Landini: Nearly all our projects are driven by commercial success. Sometimes this is achieved by repositioning or modernizing a brand, however in this case we were just being true to McDonald’s core values of innovation.

This McDonald’s is a bespoke version of our global retail format ‘Project Ray’ that we have been designing the world over for this client. We like the transparency of the idea—literally and figuratively—and how its form was a response to a challenging space that led us to stack the kitchen above the servery. The material palette is timeless: concrete, glass, stainless steel and oak.

ID: How does this project stands out from other retail projects?

ML: It seems that hamburgers in paper bags, descending from kitchens above, are interesting enough for people to share with their friends. For this project we used an electronic ordering system—pre-dating COVID-19—and vertical transportation.

American architect Louis Henry Sullivan wasn’t being ironic when he claimed that “form follows function”—albeit referring to skyscrapers and not sky kitchens.

ID: What else have you worked on recently?

ML: ALDI Australia recently commissioned us to help renew their format. Within three years, all of the retailer’s 650 stores adopted our design. We then helped them launch in China—AlDI’s competitive differential in that market is quite different, so the format and design solution are too.

ALDI has a unique business model and format. Other supermarkets, however, haven’t really challenged the original idea invented in the U.S. after the Great Depression. So when we were invited by Italian supermarket Esselunga to do just that we were excited. We considered how supermarkets might give customers a richer, more relevant experience and challenged everything. Esselunga makes a lot of really good food and they are loved for that, but they never show anyone that they are making it. We shifted payment from the store’s entrance to less costly space at the side and added a visible production centre, allowing patrons to directly experience the food being made. We then turned and triangulated the grocery aisles so you can see what’s in them. It sounds simple, but actually it’s revolutionary, ‘a wolf in sheep’s clothing.’ Everyone puts the checkouts in the front and people hate checkouts, they hate paying, why would you use that as an expression of what you do?

Great retail and hospitality have always been about the people who provide and receive it and a value equation on how costly or efficient that is to do. As such, pretty much everything we do is driven by expressing the manufacturing and hiding the payment. This project is a celebration of what we all like (making and consuming food) and a concealment of what we don’t (queuing up to part with money). When the client is inclined to do things that are revolutionary, it is very easy to reinvent normal.

ID: What’s upcoming for you?

ML: We recently have started projects in Japan, Egypt, and Greece. The most overused phrase in client briefs a few years ago was ‘make it authentic,’ followed by ‘make it Instagrammable,’ and now it seems to be ‘top secret.’ Over the years, there are certain projects that we’ve worked on and been paid substantial fees for that we will never be able to talk about which is a great shame because there are those we’re really proud of, and we’d love to have our name attached to them.

Contracts are more and more severe and secrecy has returned in spades as everyone is trying to find some point of difference in this COVID-challenged world.

ID: How do you think the world should respond to COVID-19?

ML: No one—government, general, or genius—knows quite where today’s changes will lead. In this moment, many of our clients are speculating, and many of our collaborations will demonstrate this soon. I’m an optimist—I think COVID has taught us to share better, live in the moment, and not waste time. After all, we got used to not traveling quickly enough.

As such, I predict that local may be redefined. We’ll talk more, make real friends, or go in search of more community-based experiences.

If I’m right, great brands will continue to be defined by their real and enduring personalities as opposed to artificial ones. This will impact everything, particularly brands whose essence is manufactured.

Now more than ever, brands need to be brave. Not being brave is the same thing as being stupid. I’ve always been intolerant of mediocrity, laziness, and lazy thinking. Be bold, be brave, and if you can’t, just make sure you’re not boring.

Increasingly, space is becoming an issue: what you do with it, is it safe and is there another, better way to use it? I love the idea that pop-ups might replace flagship stores—not in every category but possibly in some. The purpose of a flagship store is often to sell ‘the dream’ of a product or brand, or at least to confirm it. As we are now increasingly conditioned to transactions in a virtual world, it’s less important to use a physical building as part of this dream.

ID: How do you think your childhood or formative years influenced your design thinking?

ML: A love of food, its purchase, preparation, and enjoyment with family came from my Italian aunt, Zia Maria. She loved taking me to markets, churches, and cafes, and I spent a lot of time living with her in Rome in my teens and early twenties. Baffled by her habit of visiting the local food market three times a day, I asked her, “Zia, why don’t you go just once and stock up the fridge?” She clipped me around the ear and said: “I don’t go to the market to buy food; I go to meet my friends and gossip!” This education on the relationship between food and life has never left me and informs all of Landini’s work, as well as my day-to-day personal life.

I was also educated by Benedictine monks, so they had churches in common.

ID: Who in the industry do you particularly admire?

ML: In design, too many people take themselves too seriously. I take the job of design very seriously, but I don’t take myself too seriously. So I don’t mix with or admire too many designers … A few exceptions, include English designer, Rodney Fitch, because he was a good guy who loved people and threw great parties and my daughter’s Godfather, Tom Dixon, who is probably my best friend. He’s just funny and as an Englishman, I enjoy humor. We’ve known each other since the early 1980s when he was welding and part of what is being called the Creative Salvage movement.

ID: In what kind of home do you live?

ML: My wife Rikki, family, and I travel between an isolated beach and Sydney. I tend to spend money on things that are simple and classic, such as a Camaleonda sofa by Mario Bellini—a relaunch by B&B Italia—or a 1972 BMW CSi.

I’ve collected Tom Dixon’s stuff for years, and my house is full of it. A lot I’ve bought off him for hardly anything. One chair I bought for around $200, and then saw one on sale in an antique store in Paris for over $80,000. I wish I had bought more!

ID: What are you reading?

ML: A rare book that my wife discovered on the Creative Salvage movement called “Cut and Shut: The History of Creative Salvage” by Gareth D. Williams. It reminds me of how young and good looking we all once were…

ID: Do you have a secret you can share?

ML: I spent two weeks eating Saltimbocca Romana in Rome twice a day. That’s a classic Italian dish of really thin veal cooked in a frying pan. What you do is heat up butter and olive oil and cook the veal seconds on both sides. Then you throw in half a bottle of wine, mix it with olive oil and the butter, and reduce the sauce down really quickly and throw it on the veal. That’s it. I was searching for the best in Rome until I found D’Angelo Pasticceria on the corner of Via della Croce and Via Bocca di Leone, not far from the Spanish Steps in Rome. But you can’t eat this dish with friends because they might order something that takes half a day to cook. It’s a very selfish dish—you have to have it instantly.

Read next: Moscow’s Flagship McDonald’s Undergoes a Renovation to Entice its Urban Clientele