10 Questions With… Päivi Meuronen

“Nature is important to most Finns and similarly to me as a key source of inspiration,” says Päivi Meuronen who can be found—during winter months—Nordic skating on the archipelagos of the Baltic Sea. Since 2003, leading a team specializing in interiors, Meuronen has been wielding her creative eye as interior architect and creative partner for Helsinki-based firm JKMM Architects.

Founded in 1998 and today with a staff of 100, JKMM has an underground extension of The Amos Rex art museum in Helsinki and the Seinäjoki Public Library in Seinäjoki, Finland, a project which embraces the modern needs of today’s library among recent projects. Most recently, the firm won a competition—out of 185 entrants—to design an addition to the National Museum of Finland. Interior Design sat down with Meuronen to hear more about the National Museum’s jury-seducing floating concrete roof, a childhood fictional heroine, and a virtually untouched island just 15 minutes by sea from Helsinki’s city center.

Interior Design: Could you describe the overall design goal of your addition to the National Museum of Finland?

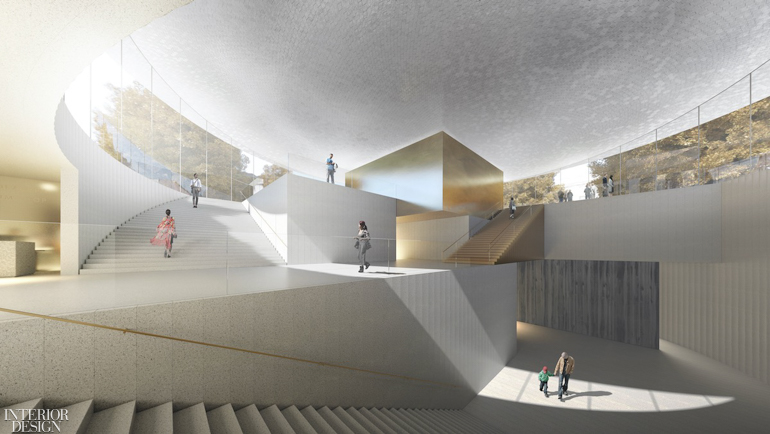

Päivi Meuronen: The National Museum is a place that belongs to everyone and anyone in Finland, and we thought the architectural form of its extension should be universally understood yet encourage multiple interpretations. It was also important to us that the subtly sculpturesque addition is independent of the existing building by Gesellius, Lindgren, and Saarinen and respects the historic garden and the National Romantic architecture of the museum building.

The external and internal worlds of the annex are connected through the floating concrete roof that introduces natural light to the floors below, where a generous, protected and stepped public square welcomes visitors and leads them to the new exhibition galleries. The furniture in the new annex will be custom-made and—together with built-in pieces—these will be an all-important component in the architectural expression of the building.

The way visitors orient themselves in a museum is very important and matters from the point of entry, to their experience within the museum, and to how they leave the building. In our ‘Atlas’ scheme for the National Museum of Finland, we really wanted to create a building that will enhance visitors’ experience by improving both the way they are received and overall circulation. I think the jury appreciated this.

ID: What else have you completed recently?

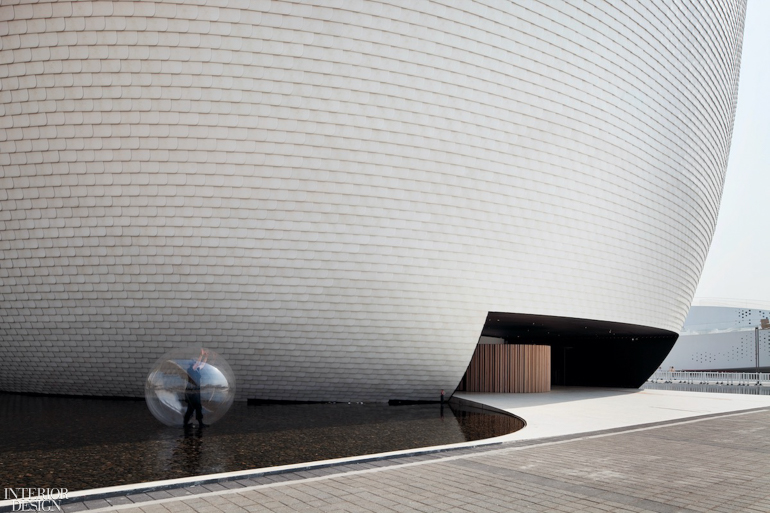

PM: An extension to the Amos Rex art museum in central Helsinki. The goal was to join the past—an existing 1930s listed Functionalist pavilion—with the present, the much needed new galleries.

In the beginning we were asked to investigate if the pavilion could provide the spaces, but because it was protected, we decided to go underground. However, we didn’t want to go totally underground. So we decided to pop up in a public square with these rooftop shapes, using this very old cupola structure. A cupola is self-baring construction—so you don’t need any pillars or walls—allowing open space. The hills in the square are the only visible facade of the new museum.

The roof lights create a sculpturesque effect and are important in connecting the galleries to the city, and we framed the views to enhance this sense of belonging to a place.

The soft curving shapes of the exterior also inform its interior and can be seen in the forms of the furnishings, the mosaic tiles and the details. A light installation mimicking natural light covers the ceiling of the generous cloakroom area and helps illuminate the underground spaces.

ID: In what field have you seen significant change, design-wise, over the years?

PM: In Finland we see libraries as educational buildings. Having designed the interiors for a number of these, I have witnessed how the role of the library has recently undergone a transformation, reflecting fast changes in society and the ever-increasing forms for storing and handling information and books.

The library is more dynamic now, and no longer a place just for reading or information. In Finland, especially, libraries are places for new experiences, for hanging out, for work, for finding new hobbies. They are also important places for meeting people and community interaction.

We recently worked on the extension of an Alvar Aalto-designed library in Seinäjoki in central Finland, the Seinäjoki Public Library. Once you enter the library, the whole space opens to you at once, with this amphitheater-like space at the core of the building. We thought of this as a place not only for sitting and reading, but also as a venue for presentations, dance, or musical events.

The client asked us to focus on the children and youth departments because they are really the future library users. So we did very nice children’s department following the theme of a Finnish fairytale, with all flooring, walls, and ceiling covered with carpet. Since it’s very good acoustically, it’s a place children don’t have to be afraid to make some noise.

On the lower ground floor, we have these holes, these niches in the wall, which are quite deep. When you go down there, you don’t see any youngsters, but you see tons of shoes because they leave their shoes on the floor and jump into the holes.

ID: What’s upcoming for you?

PM: I am in the midst of designing an interior concept and the first flagship store for a Chinese internet coding school that already has hundreds of thousand online users. The aim is to offer the client innovative and inspiring teaching facilities that encourage children of different ages to be experimental and, of course, to learn.

ID: In what kind of home do you live?

PM: I live with my husband Aimo Katajamäki, a graphic designer and sculptor, in central Helsinki. It’s an area known for its Jugend style architecture and we occupy a house inside an inner courtyard formerly used by the gatekeeper of our apartment block. Some much-loved furniture from my grandparents includes an armchair by Finnish designer Ilmari Tapiovaara, which needs a thorough restoration. In all seasons, my grandmother kept it on her balcony—even using it to feed birds.

ID: How do you think your childhood influenced your design thinking?

PM: As a child I read loads and found my heroine in Astrid Lindgren’s Pippi Longstocking. Anarchist Pippi was independent, the world’s strongest girl who did what she wanted. I really admired her. I don’t have kids of my own, but have designed lots of spaces for them—libraries, schools, daycare centers. To reconnect with a child’s perspective of what works and what doesn’t, it helps to look at the world through Pippi’s eyes. Pippi’s example has, I hope, also had an impact on my professional courage and my voice as a designer.

ID: Is there someone in the industry that you particularly admire?

PM: The grand old lady of Finnish design, Vuokko Eskolin-Nurmesniemi, is my idol. In the 1950s she began work at Marimekko and her simple, iconic dresses found their way into Jackie Kennedy’s wardrobe. In 1964, she created her own Vuokko label. She’s an extreme advocate for a reductive aesthetic that celebrates clean forms and graphic clarity and has always been loyal to her own sense of style. She just turned 90, but you can still come across her serving customers in her shop.

ID: What are you reading?

PM: I really like books by Japanese author Haruki Murakami, and return to these from time to time. Most recently, I re-read “Sputnik Sweetheart”—for its open-ended storyline and the lingering, strange atmosphere of the narrative.

ID: Do you have a secret you can share?

PM: Fifteen minutes by sea from Helsinki’s city center and you’ll reach Isosaari, a public island which for many decades was off limits and closed to the general public as it belonged to the armed forces. Now in the summer months you can reach it by boat from Kauppatori, the main market in Helsinki. On the island you’ll find perfectly smooth bedrock that lends itself to quietude and solitude. There you can watch the horizon while enjoying a picnic packed from the market. The nature on the island—with its distinct vegetation and flourishing fauna—is virtually untouched.

Keep scrolling to view more of Meuronen’s work >