10 Questions With… Phil Freelon

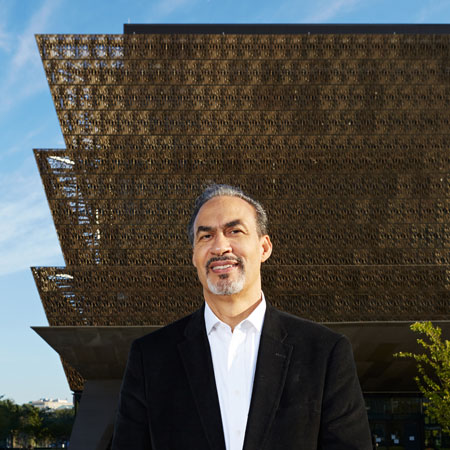

Not many architects get to work on a project as significant as the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC). Even fewer get to design for a site as momentous as the National Mall. Phil Freelon now has done both. He was the lead architect for the new museum in his role as the managing and design director of Perkins+Will’s North Carolina practice.

Not many architects get to work on a project as significant as the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC). Even fewer get to design for a site as momentous as the National Mall. Phil Freelon now has done both. He was the lead architect for the new museum in his role as the managing and design director of Perkins+Will’s North Carolina practice.

This milestone, one that left him “awestruck,” is a fitting culmination of three decades in the industry—first at his own firm, Freelon Group, and then at Perkins+Will, after his practice was acquired by the firm in 2014. He’s designed projects such as The Museum of the African Diaspora in San Francisco, Emancipation Park in Houston, and the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta. Freelon, a faculty member at MIT, is eager to share his experience with aspiring architects. Recognizing design’s diversity problem, he established a fellowship at Harvard to introduce students of color to the profession. Here, Freelon talks about the NMAAHC commission and his heightened interest in accessibility following an ALS diagnosis.

Interior Design: What was it like working on the NMAAHC?

Phil Freelon: Working on such a highly visible and sensitive site in the nation’s capital was exciting. Engaging the numerous regulatory agencies, while addressing the needs of the Smithsonian Institution, was quite challenging.

In order to adhere to the building height restrictions in Washington, D.C., the design team had to limit the amount of structure visible above ground. This was achieved by excavating the site to a depth of 85 feet so that significant portions of the museum could be placed below street level. The high water table in D.C. further complicated this approach.

Integrating exhibits with architecture and interiors was a primary objective. The goal was to reach beyond the gallery walls, through the public gathering spaces, and out into the landscape.

ID: How did working on the museum compare with your experience designing other cultural projects?

PF: The NMAAHC was larger than other cultural projects. The broad sweep of history and deep thematic content were beyond other museums we have worked on. Collaborating with three other architectural firms [Davis Brody Bond, Adjaye Associates, and SmithGroupJJR] was unique, challenging, and quite rewarding.

ID: Tell me about the Philip Freelon fellowship at Harvard. What inspired you to create it?

PF: Diversity and inclusion have long been challenges for the design professions. The fellowship is a way for me—in partnership with my firm, Perkins+Will—to make a difference by providing financial assistance to deserving students of color.

ID: The design industry is predominantly white. What do you think needs to happen for that to change?

PF: Change starts with awareness. Many young people are simply unaware of design professions as viable career options. More role models teaching in our design schools is also essential.

ID: How do you talk about this issue with students?

PF: I show them how wonderful and rewarding a career in design can be. And how their creativity can make the world better.

ID: Which person, place, or thing—inside the industry or out—inspires you?

PF: The capacity for built form to engage, enlighten, delight, and inspire others inspires me. When I see examples of this, I am reminded that my work can have a positive impact on the people who encounter it.

For example, when NMAAHC opened in September, I was awestruck by the number of people who were drawn to the building. Hundreds of visitors lined up for the opportunity to enter.

ID: Latest design obsession?

PF: Amplifying the Motown story by creating a visitor experience worthy of this incredible music and American institution [for the Motown Museum in Detroit].

ID: Latest interiors pet peeve?

PF: Barriers to accessibility. In the spring of 2016, I was diagnosed with ALS, a progressive condition that affects the nerve cells that control the body’s muscles. I struggle to navigate stairs, curbs, and even relatively small elevation changes in walking surfaces as I adapt to decreasing mobility. Moving toward the use of a powered wheelchair, I will soon view my environment from a vantage point well below standing height. This will certainly change my perception of the built (and natural) environment.

I have always been aware of and responsive to universal design and accessible design initiatives in my work. Facing disability at this stage of my life was unexpected. The challenges have heightened my awareness of and reaffirmed my commitment to accessible design.

ID: A secret source you’re willing to share?

PF: Parlour, a local ice cream parlor in Durham, NC.

ID: Dream commission?

PF: The Obama Presidential Library.