10 Questions With… Theater Designer Es Devlin

British multidisciplinary Es Devlin has been at the forefront of theater design for over three decades. In that time, the trained artist and literary scholar has worked hard to break down the traditional hierarchy of high and low art—the notion that painting supersedes performance and pottery in between. Collaborating with both cultural and commercial patterns in equal consideration, Devlin has been able to re-invigorate the proverbial “stage” with her own brand of blended media: achieving the maximal experiential impact for the visitors of a sound-washed labyrinth installation developed with Prada or the audience of James Graham’s Dear England play at London’s National Theatre.

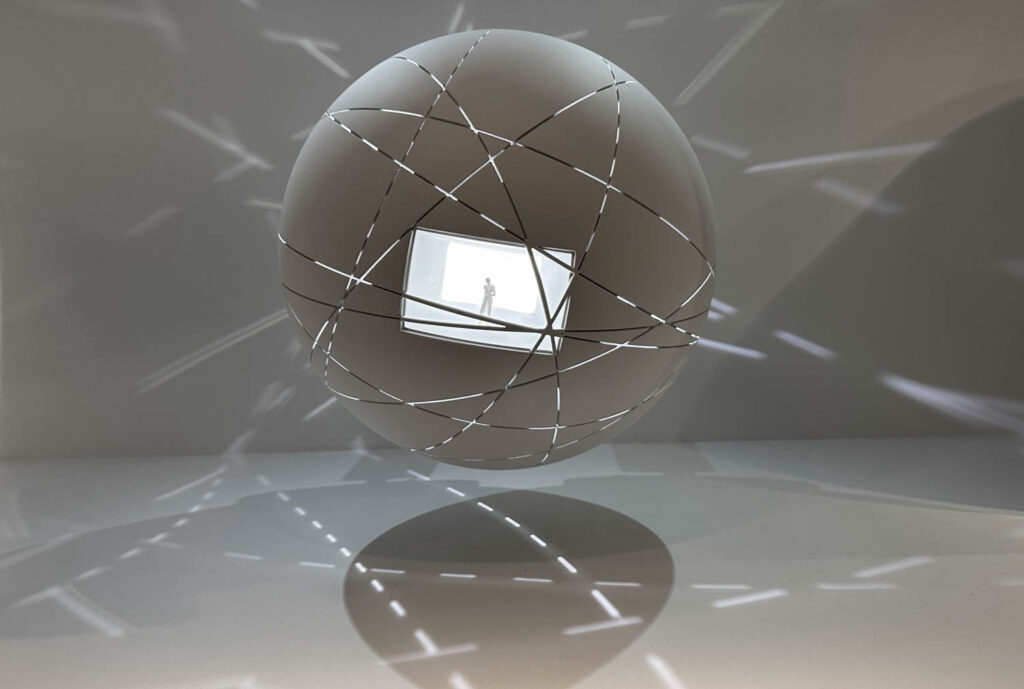

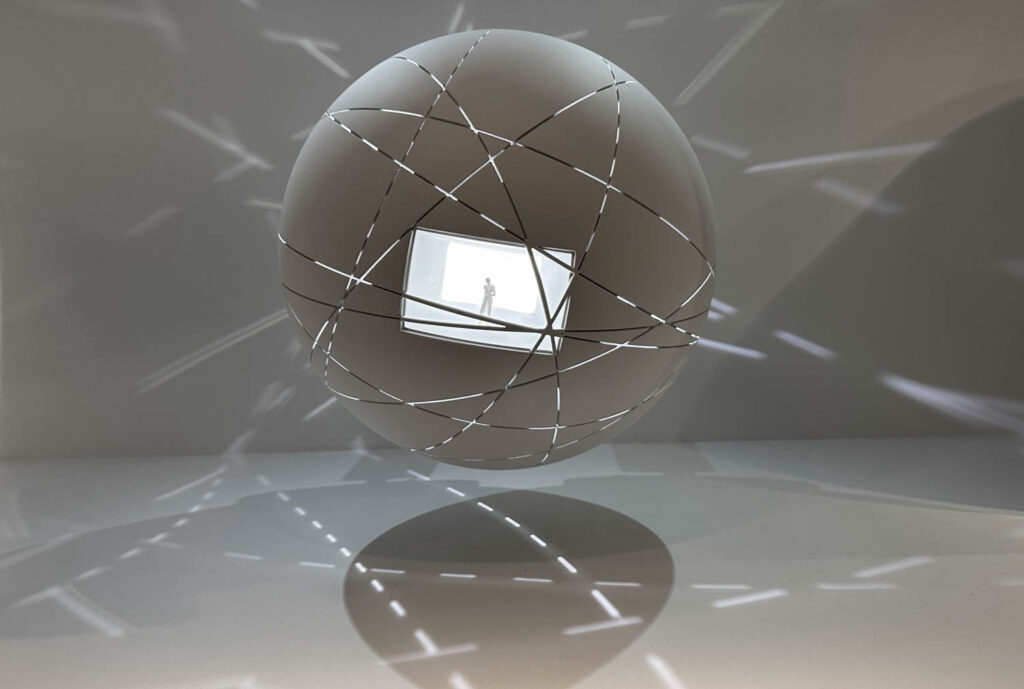

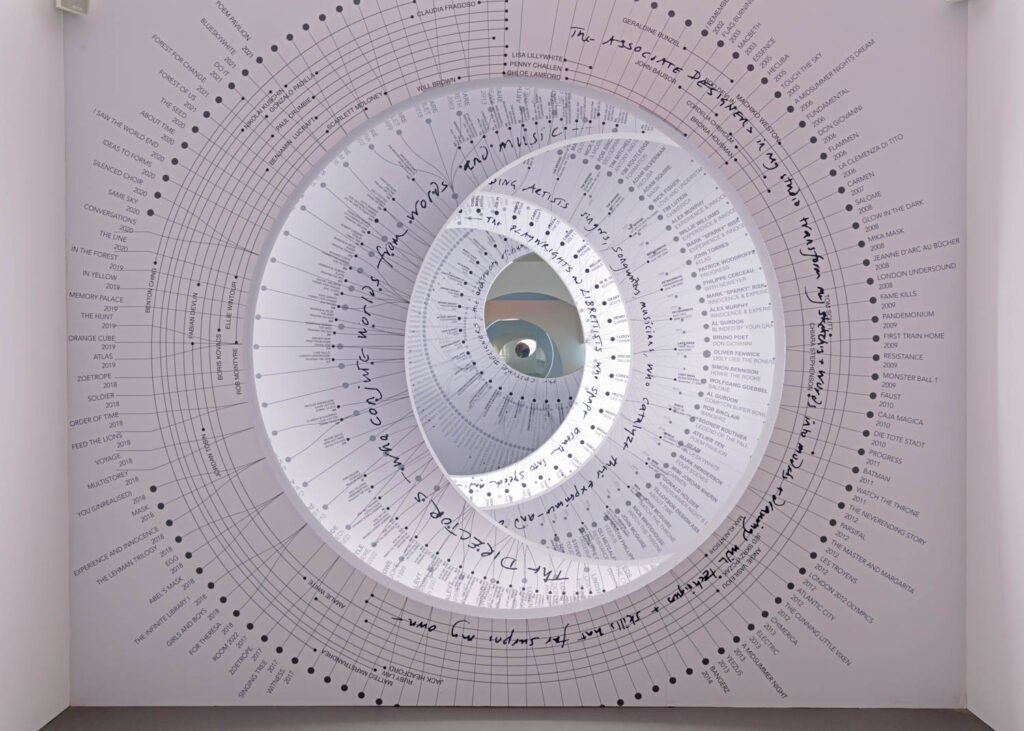

Though mapping light, folding in projected film, and integrating kinetic sculpture have been her signature devices, the polymath set designer continues to investigate and harness new technologies. Devlin effortlessly transitions between the worlds of narrative opera, music, fashion, film, architecture, and design. Major projects have included the staging of big budget Beyoncé, Adele, and U2 tours; the 2012 Summer Olympics London closing ceremony; and Singing Tree, a collective choral carol installation mounted at the Victoria and Albert Museum during the 2017 holiday season.

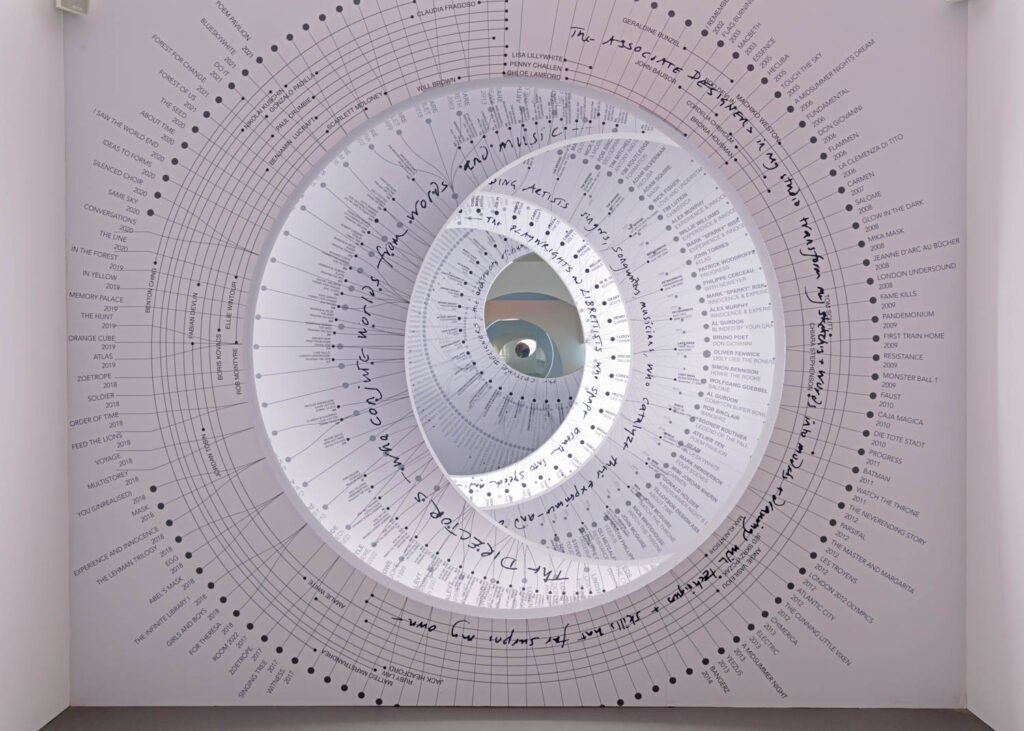

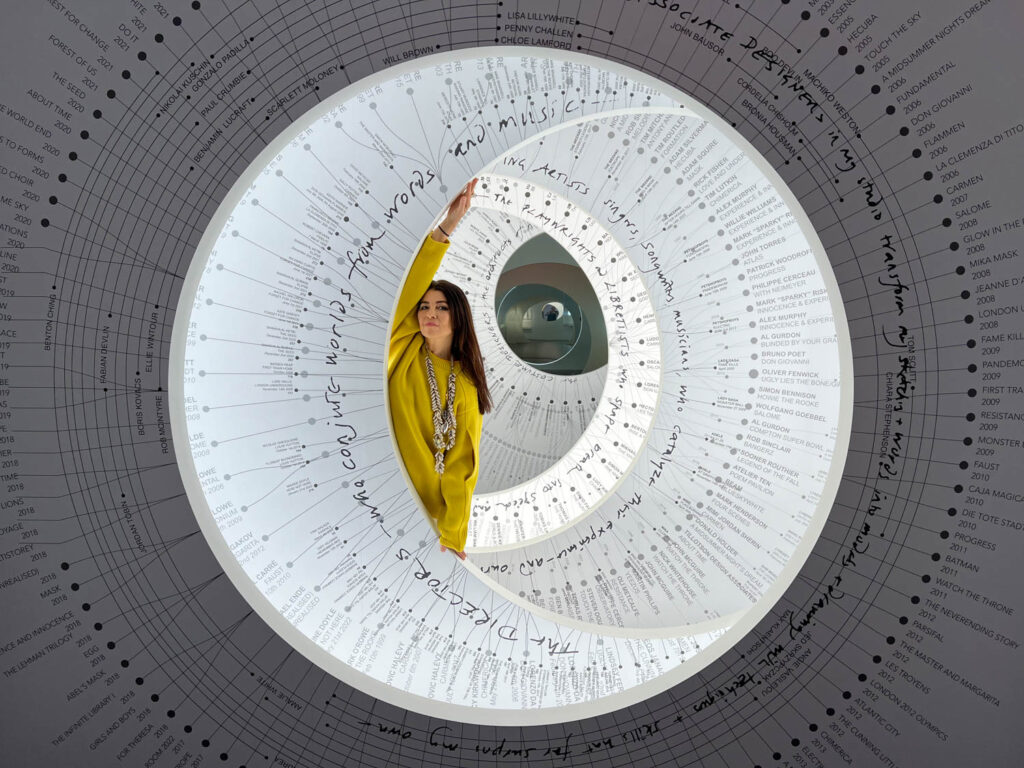

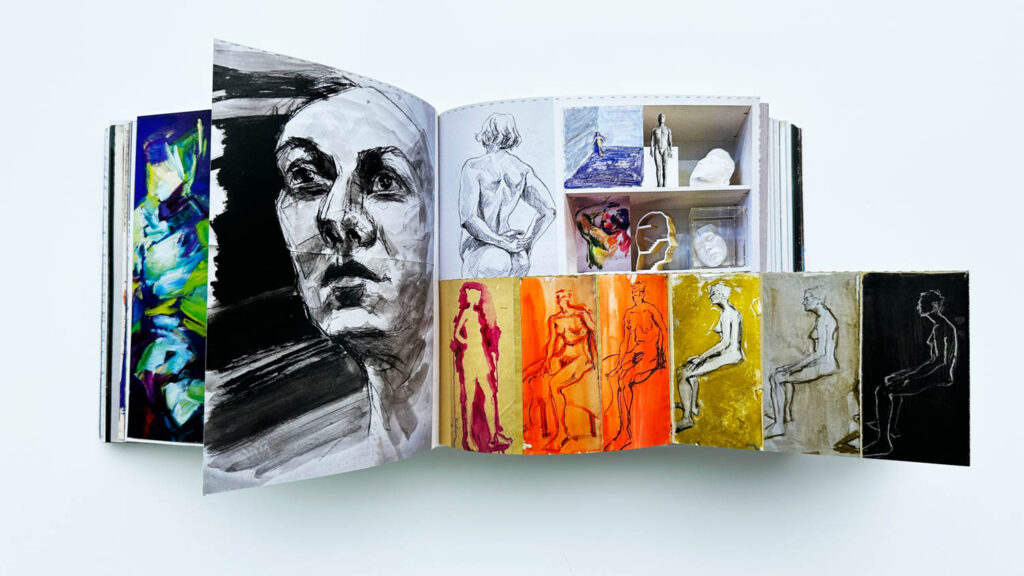

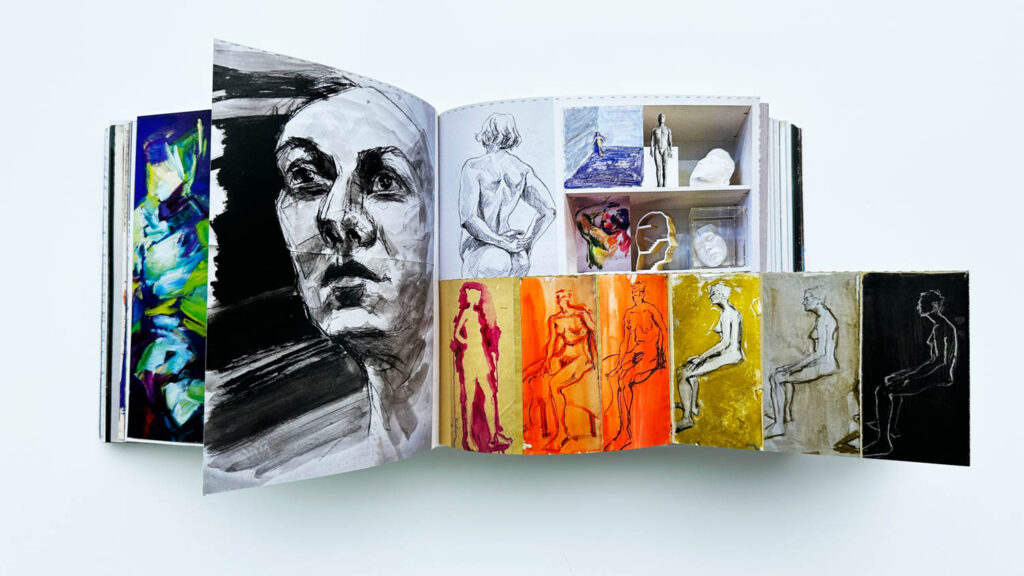

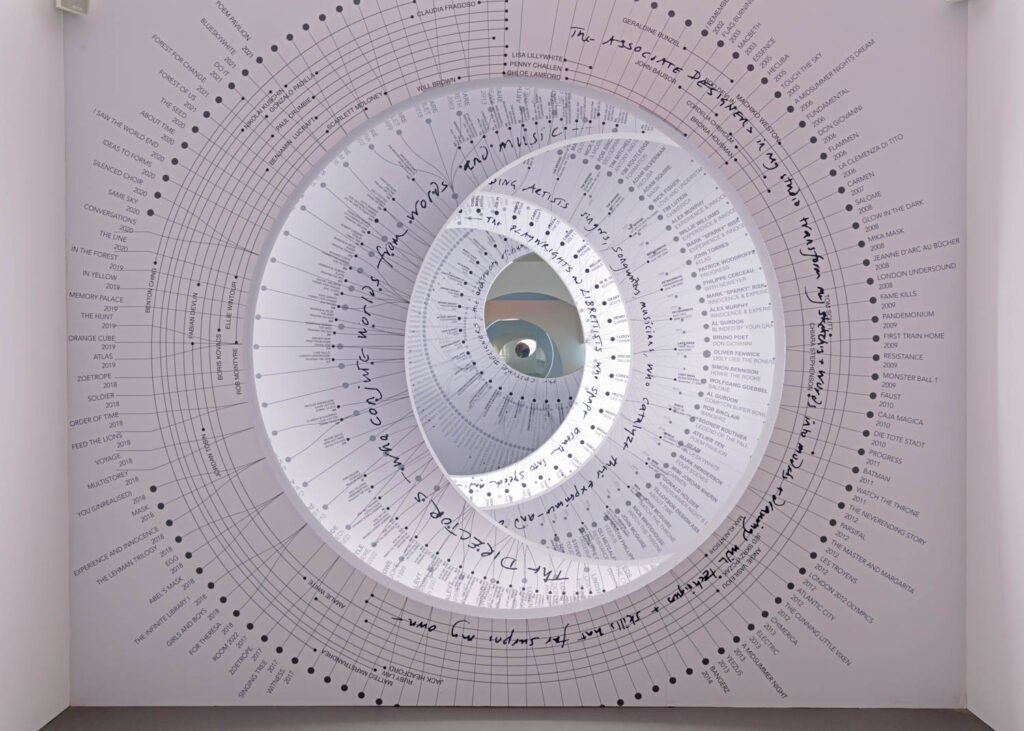

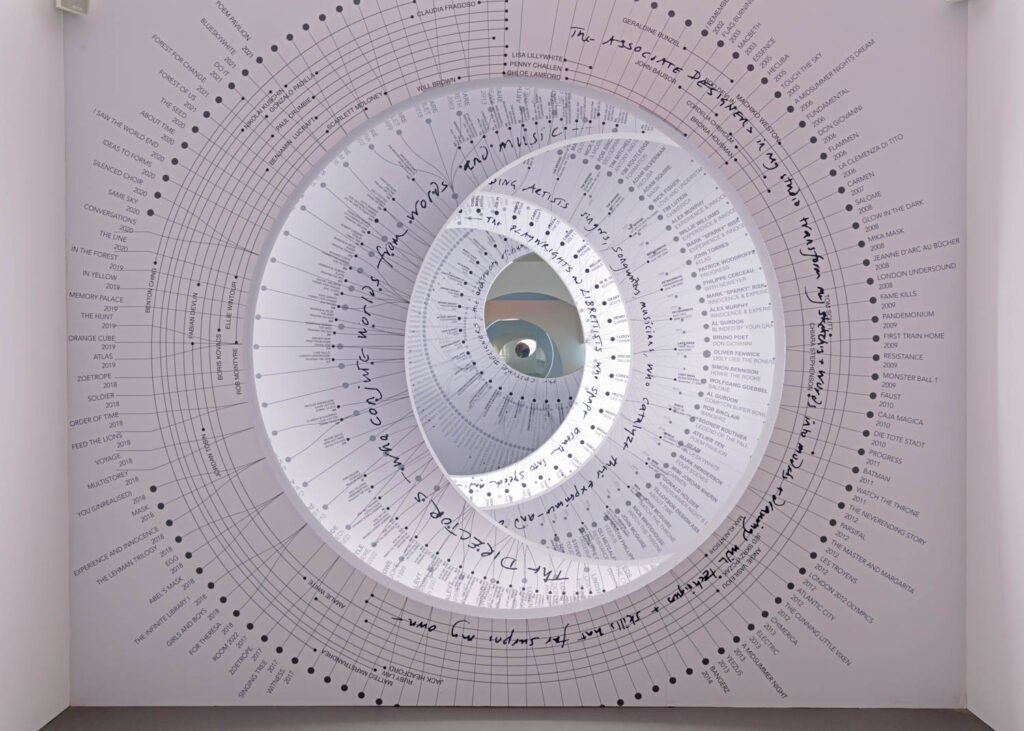

On view at New York’s Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum through August 11th, An Atlas of Es Devlin is the widely celebrated talent’s first monographic exhibition. Accompanying a comprehensive book with the same name and co-published with Thames & Hudson, the show places particular emphasis on her iterative and discursive process. The dynamic showcase incorporates hundreds of maquettes, sketches—some even from her early art school days—and other preparatory material.

Here, Es Devlin speaks to Interior Design about her non-linear path to interdisciplinary theater design, her creative process, and what this first retrospective has provided in terms of being able to self-reflect on her career so far.

Es Devlin Goes In-Depth About Her Background and Process

Interior Design: What first drew you to theater design?

Es Devlin: I finished my foundation course at Central St. Martins College of Art in 1992 and by summer 1994 was assisting on the production of a Damien Hirst opera project at the Edinburgh Festival. I was set to continue my studies at Central Saint Martins that September, making layered prints and books. I’d picked out my spot in the beautiful, empty white student studio spaces on the Southampton Row campus.

But on the advice of various tutors, I visited a small red studio in the scene dock of the Theatre Royal Drury Lane where 10 quite feral-looking Motley Theatre Design Course students appeared to be living full time. They were making scale models, listening to opera, annotating texts, and eating pot noodles under the direction of the legendary 93-year-old theater designer Percy Harris, the renowned opera and film designer Alison Chitty, and the ethereal artist and set designer Kandis Cook.

ID: Did the notion of being able to integrate different disciplines within a single creation—the total work of art doctrine—factor into your decision to pursue and eventually shape this domain?

ED: The studio felt like a convergence of art, film, and music as well as theater. I walked in and didn’t want to leave. I had a sense that the beautiful, empty white studio would still be there when I was ready for it, but for now, among this noisy, red rag-and-bone shop, I had found my tribe. These three powerful mentors taught me the importance of protecting the clarity of an idea while trusting the emergence of work through collective, collaborative process. They were also profoundly intolerant of anything that didn’t contribute to the meaning and purpose of a primary text.

ID: Looking at your practice today, how is it different to conceive a scenography for a major opera house production and stage a fashion show or concert?

ED: In some ways I see my practice in light, sculpture, music, and text as a 28-year extension of that corridor: sometimes walking or reading alone, often running at speed, usually holding hands with collaborators: musicians, poets, engineers, directors, dancers, philosophers, and activists. The techniques we use may vary depending on the genre, however the intention remains continuous across any perceived boundary. No matter what scale the space, every project begins with a mountain of research that ends up equally high.

ID: Are there still strict boundaries between cultural and commercial endeavors?

ED: Rather than existing between boundaries, I think the work takes place on a continuum: something like a corridor. When I was around eleven years old, I remember standing in a long hallway of a music school hearing fragments of Bach being played on a piano through one door, a trumpeter playing Miles Davis through another, a guitarist playing Led Zeppelin through yet another door, a soprano singing Mozart through another. I remember admiring the beauty of each of these musicians and composers, and then observing that equally miraculous moment within the place where I stood, in that particular shaft of sunlight, where these fragments of music, light, and atmosphere coalesced into something new and unnamable.

ID: In what ways do you look to integrate the latest technologies while still implementing analog techniques, both in terms of your process and finished results?

ED: Each project begins with an evolving intention. I seek technologies that will help to express the intention and the ideas. It’s often an equal mixture of analogue, ancient, digital, and contemporary. I think human bodies and minds evolve more slowly than our technology and tools. I believe we still long to exist in a physical place on the planet and to exist in relation to one another and to the more than human species of the biosphere. I am particularly interested in using technology as a portal to rootedness in place and planet.

ID: In what ways has the An Atlas of Es Devlin exhibition at The Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum allowed you to reflect back on three decades of your practice?

ED: Until now, I have rarely stopped to look back. The book, and its accompanying exhibition, An Atlas of Es Devlin, are attempts to collect the traces that have been left, to seek the connections, recurring interests, and forms that have resurfaced throughout the practice.

ID: What has the exhibition and the process of looking back at the materials of past projects revealed about your way of working that wasn’t, perhaps, evident before?

ED: Both the book and the exhibition aim to express the evolving intentions over 30 years of practice, which have found their focus particularly over the past decade since I read Naomi Klein’s book This Changes Everything. Many of us are seeking ways in which our crafts can find the most resonance amidst the climate and broader civilizational crisis we face.

ID: How has this retrospective influenced your current preoccupations; concepts being developed both of your own free ideation and with/for different partners?

ED: A theater maker’s daily practice involves imagining worlds that don’t yet exist. Our work is inherently collaborative, made by a collective of practitioners for a collective audience. We invite audiences into experimental perspectives that neither they nor we have previously inhabited. We see an audience as a temporary society, a community that arrives in one state, sits closely together in the dark for a few hours and departs in an altered state: the architecture of their minds redrawn not by facts but by feelings. Perhaps the techniques we have developed together to amaze our audiences may prove useful in the pursuit of broader cognitive shifts.

ID: What for you have been major changes in your practice and the type of projects you’ve taken on in those three decades?

ED: During the first decade of practice I worked primarily on text, on drama. The second decade led to opera and large scale concerts, the past decade has been focused on large scale public choral installations in museums and galleries that invite the audience to become participants and co-authors of the work. I continue to work in theater, opera and museum spaces and I am very much enjoying making books. While a large scale performance or art installation often feels like a rush of centrifugal energy pouring out of the studio, a book feels more like a gathering of forces towards a concentrated miniature that can be passed from hand to hand.

ID: What are some of the projects you’re currently developing?

ED: At the moment we have a number of projects being presented in North America including: Forest of Us, a large scale installation at Superblue Miami; The Hunt, at St Ann’s Warehouse, Brooklyn; An Atlas of Es Devlin at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum NYC; Don Giovanni at the Canadian Opera Company Toronto; Bad Bunny, Most Wanted Tour, on tour in North American arenas. In London, The Motive and the Cue is playing at the Noel Coward Theatre and in Sydney , The Lehman Trilogy plays until 24 March, before opening in San Francisco on May 25.

read more

DesignWire

Historic Washhouse in Italy Earns Verdant Makeover

The 2024 Landscape Festival in Bergamo mixes lush greenery with colorful outdoor furniture from Pedrali at Antico Lavatoio, a historic wash house.

DesignWire

10 Questions With… OWIU Founders

Amanda Gunawan and Joel Wong of OWIU share their design ethos, love for expressive materials, and how their roots impact their work.

DesignWire

Wangen Tower Surfaces As A Bold Landmark In Southern Germany

Wangen Tower pioneers a humble building material into a soaring, staggering landmark in southern Germany.