10 Questions With… Tina Hovsepian

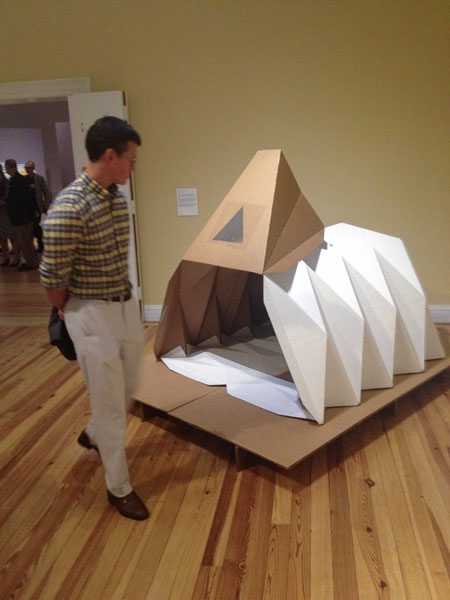

An inspiring young talent in the architecture industry today, Tina Hovsepian is the creator and founder of

Cardborigami

, a fold-out “instant space” device made of cardboard that has put an exciting new spin on the notion of shelters for the homeless. The invention—her college project at USC which landed her a plum gig as an associate architect at

Callison

last Spring—has matured into a wide-reaching, philanthropic effort that includes macro plans for the creation of jobs for homeless individuals and, further off, low-cost housing development. Here, we ask Hovespian how she’s managed to accomplish so much, and explore the big thinking that seems to be sending her to the top of the industry.

Interior Design: Tina, you graduated from USC in 2009, and yet you’ve already made a big impression on the design industry with Cardborigami and your general approach to design. How did you do it?

Tina Hovsepian: I’ve always wanted to do something that would make an impact. In architecture school, we learned a lot about sustainability, the environment, and global warming—the kind of issues that we, as a society, have been causing ourselves. I was also the president of AIAS on the USC campus, and had my hands in a number of volunteer-related initiatives. I guess I really dove into things, and have been interested in how architecture and the “business of building” either improves issues or makes them worse. Meanwhile, Cardborigami is a social endeavor. I began studying and practicing Buddhism, embracing this notion that every individual has potential for greatness—that we should have the same respect for a homeless person that we do for the president of the United States. I traveled to Southeast Asia—Thailand and Cambodia—and saw third-world poverty with my own eyes. We were there to redesign an elementary school, and I got to interact with the kids. It had a big impact on me. When I got back in 2007, I designed Cardborigami for my semester’s open-ended project. I wanted it to help the homeless population of Skid Row in Los Angeles.

ID: It’s been great to watch Cardborigami get such great recognition—a strong idea that makes a big impact. What’s the latest on this initiative?

TH: We’ve been working on the development on a “four step linear pass” out of homelessness, going to Skid Row many times, informally speaking to a lot of people who live on the street. We’ve showed them our shelter, asked them questions. What do they really need? Would this really help? Through that process, we’ve come to see that anything that is a “handout” is not really helpful. The only way for people to transcend that situation is for them to help themselves. Thankfully, the shelter I designed works well within the plan.

ID: In what ways are you able to actually engage those who use these shelters in a socially transformative way?

TH: There’s an opportunity for people to be involved in the construction of their own shelter, or in shelters for others. This is the first situation for some of these people to do something for themselves in a long time. This is not happening on the street; the shelters are not being given out. Obviously, it’s not safe for people on the street, so we’re partnering with other organizations, one of which provides a safe space, without beds, within which these can be used. People can check into the program, use the shelters on the safe property, and while there gain knowledge of and access to services. LA is very spread out, so we want to fill the gaps and provide a psychological jumpstart if we can.

ID: What are the next steps for participants in the organization?

TH: The third step we’ve set out to do is to help people get into permanent housing, which is related to the fourth step—the hiring of people who go through the program to construct shelters. These last steps are key for us, since the opportunity to hire people offers sustainability, which is more important for the individual. We’ve been lucky enough to get the help of the Annenberg Foundation, which provided us with a training program that has helped us—and other nonprofit organizations—become efficient on a business level.

ID: What was the feeling when you successfully created your first Cardborigami prototype?

TH: I really realized what it could potentially do in the real world during my final review. We were tasked with building a full-scale model of our project. I had 500 dollars to spend, and built this huge, collapsed version of my shelter. Closed, it was one-and-a-half feet wide. During my review, we all opened it together and it was a huge spectacle. That was a wow moment. I thought,

What have I done?

It was a shock. One of my reviewers said, “You should take this idea to the mayor.” And she was serious. In 2009, I submitted the project to compete in our undergrad symposium for creative work. I won the prize for innovation and they got me connected with everyone who’s allowed me to develop the idea, to make it smaller and more portable.

ID: What have been the biggest challenges of getting this idea off the ground?

TH: The challenges have been philosophical. People are used to doing things in a specific way and it’s hard to get them to try something new. We’ve repeatedly come close to getting partnerships, yet right before it comes to fruition we’re told it’s “too risky.” That’s been the most difficult part, but there has been a lot of support from our volunteers, and people contacting me without having to solicit help. That, and media coverage, all helps our cause so much.

ID: Meanwhile, you’ve found yourself working with Callison. What does it mean that this worldwide company has recognized your ingenuity?

TH: Yes, my day job is very exciting. I design commercial international buildings. I’m currently working on three different mixed-use developments Mexico City, which really is the new booming building environment in Latin America. I’ve been working on the front end—the conceptual and thematic portions—of these projects. It’s millions of square feet, with hotels and residential space above retail. It’s challenging, and I really love that. I also am working on a major mall redevelopment in Hawaii, and another in Nevada. What’s great is how supportive Callison is of Cardborigami. Other firms I interviewed with seemed to think of it as a conflict of interest, but Callison is so on board. After we received the first 150 shelters, we were invited to do the first kick-off event at the Callison office in LA. That means a lot.

ID: Cardborigami is a wonderful launching pad for what will be a big career. Can you tell us about your vision for the future?

TH: I think big, obviously, otherwise I wouldn’t have been able to get this far withg Cardborigami. I’ve always wanted to be a developer, to be in charge of my own work and develop what I’m working on and have my say in the design—to be both architect and client. Meanwhile I really want to build upon what we have with Cardborigami. It’s not just about a cardboard shelter. Once we get started and prove the viability, we want to develop affordable housing—which will

really

make an impact. I find it very sad that 93 percent of the people we interviewed from the streets said that the shelter I created is better than where they currently sleep. Think about it: a few miles from Skid Row is Beverly Hills. We have such wealth in this powerful nation, and we can set new standards.

ID: What advice do you have for others who might have a simple yet impactful idea?

TH: First, I say, never give up. I’ve had moments where I’ve thought,

This isn’t going to happen.

Yet I’ve stayed focused on my intention. Articles about me could go to my head and make me feel like a celebrity, but that’s a distraction. The other thing I say is, a lot of existing organizations are doing really good work. They need help, volunteers, and donors. If people would look around and be a part of the movement that resonates with them, they can feel really fulfilled. Lastly, I say, remember always that you can make a difference. Don’t be passive. Ignoring a problem adds to that problem.

ID: How did you first become interested in the design industry?

TH: My family has a long history of talented artists and craftsmen, so I think it’s in my blood. As a child, I sketched a lot. My favorite thing to draw was women’s clothing; it was my passion for a while. At some point I got advice from a family member who was in the fashion industry, who knew how cut-throat that industry can be. It was suggested that I look into architecture. There was nothing to lose in exploring it, and once I started I fell in love with it. I’m very interested in social entrepreneurship; that triple bottom line of engaging in work that makes a profit, does some social good, and is environmentally conscious. Some day, when I’m old and bored, I might attempt fashion. But I think I will get a lot more satisfaction doing what I’m doing now.