Arthur Carrara: A Paragon of Creativity

Originally posted on January 7, 2010. Carrara first came to my attention through period references to his build-it-yourself toy, Magnet Masters, a contemporary of the early 1950’s Eames Toy and a forerunner of the Danese toys and games of the 1960’s. My interest was further piqued when I acquired a copy of the 1960 Flexagon catalog, filled with visual delights and offbeat innovative ideas. I remember being surprised that this body of work was so underappreciated now. We revisit Carrara on the anniversary of his birthday.

Arthur A. Carrara (1910-1991) was a Chicago-based architect and designer whose work channeled Prairie School and modernist influences, from Frank Lloyd Wright to Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Buckminster Fuller. But for a stint in the Army during WWII, he remained based in Chicago, designing private houses, corporate offices, exhibitions, and industrial products. Unfortunately, his name is not offhand familiar today, and his work is largely off the radar. Fortunately, his idiosyncratic career was showcased in a retrospective exhibition circulated by the Milwaukee Art Center in 1960, and preserved in a graphically arresting though largely unobtainable catalog.

Titled “A Flexagon of Structure and Design: An Exhibit of the Work of Arthur A. Carrara,” the catalog provides a window into a fascinating and experimental body of work and thought.

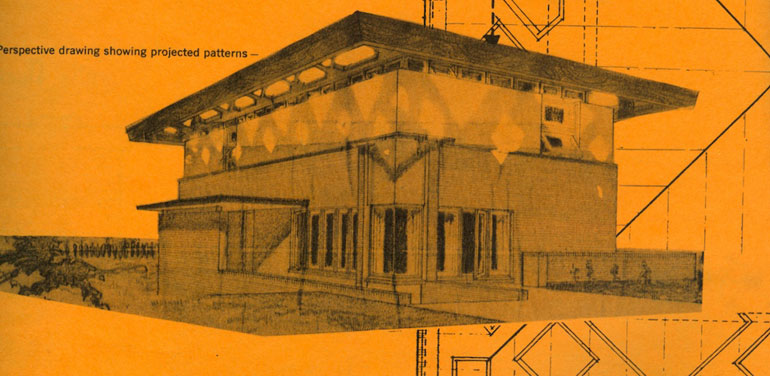

As pictured here, this work includes Magnet Masters, an architectural toy promoted by the Walker Art Institute and featured in “Everyday Art Quarterly;” Café Borranical, a model for a building incorporating hydraulic moving sections; a low-cost “keel chair” of stapled fir plywood; a model of a play sculpture submitted to a MoMA competition; a house designed for Edward Kuhn that projects a changing pattern of shade ornament; and a plastic “Inflata-Lamp,” described by the author of “The Inflatable Moment: Pneumatics and Protest in ‘68” as the first inflatable object for the home.

As titular symbol, the flexagon carries particular meaning for Carrara. Discovered by a British mathematician in 1937, flexagons “are paper polygons, folded from straight or crooked strips of paper, which have the property of changing their faces when they are flexed.” Sort of a 3-D kaleidoscope-cum-origami, the flexagon expresses creative potential for Carrara, possessing, in his words, the qualities of “mystery and precision.” This combination of attributes—mystery and precision— describes Carrara as well, suggesting a mind capable at once of mathematical logic and wonderment.

It is not surprising, then, that Carrara designed toys and play structures, and that the fulcrum of his work was imagination, play, fancy, and fun. As he said in writing about Magnet Masters, “every idea of man is first emphasized as a toy or in a toy.” Toys and play structures elicit creativity itself, introduce architecture and design as participatory acts, and embody notions of sculptural plasticity and motion. Unfettered creativity, plasticity, and motion are key elements of Carrara’s mature work, uniting his earliest and latest efforts, and his toys and buildings. In this regard, the Kuhn house takes on the aspect of a kaleidoscope and the Café Borranical that of a flexagon. Magnet Masters was suggested in “Everyday Art Quarterly” as a teaching tool for children of all ages—graduate art students included—while electromagnetism was imagined by Carrara as a method of building joinery.

Perhaps the lack of exposure makes Carrara’s work appear fresh today, or perhaps his take on things is simply refreshing. If you are fortunate enough to get hold of a copy of “Flexagon” you can judge for yourself.

An original edition of A Flexagon of Structure and Design remains both fresh-looking and elusive, while Carrara himself remains obscure. As designer and architect, Carrara merits re-evaluation—perhaps a thesis or monograph, or a museum show. In retrospect, the model of a play sculpture, pictured here, is to me the most dazzling image.