Boris Vervoordt Explains His Vision for a Converted Distillery in Antwerp

It was virtually inevitable that Boris Vervoordt, son of the famed antiques and art dealer Axel Vervoordt, would join the family firm—which also includes his mother, May, and younger brother, Dick. That was at the age of 22. A couple of decades on, Boris Vervoordt is responsible not only for the interior design business but also for the Axel Vervoordt Gallery at Kanaal, a real-estate development in Antwerp, Belgium, that makes the average multiuse project look one-dimensional.

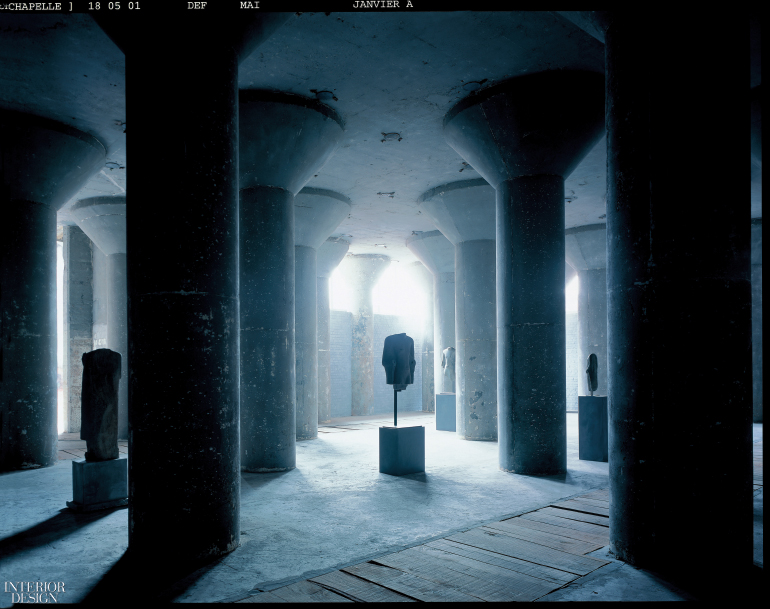

Set alongside a canal, a converted 19th-century distillery now unites residential, business, and cultural functions, with 98 apartments, 30 offices, an artisanal French bakery, and an organic food market and restaurant as well as the Axel Vervoordt company headquarters. Exhibition spaces cover much of its 600,000 square feet, showcasing both artists represented by the gallery and work drawn from the Axel & May Vervoordt Foundation. There are also permanent installations by the likes of Anish Kapoor and James Turrell.

Interior Design: What makes a great gallery of contemporary art?

Boris Vervoordt: Physically, as with all architecture, it comes down to space and light. Sun helps a lot. The space at Kanaal that we refer to as the patio gallery has the kind of light you’d find in a painter’s studio, making the art feel so fresh and immediate.

Equally vital is the right attitude. A gallery needs to be pioneering. If you’re following trends, you’ve already lost the plot. You also need to establish long-running relationships with artists. It’s like a marriage. You have to start with the idea of it lasting forever, even though divorce is always a possibility.

ID: How does your varied group of artists reflect your position as a gallery?

BV: They bridge the gap between Western and Eastern cultures, which is what we’re about. In addition, we look for social engagement. Art has a role to show us the future, to indicate how society should evolve. For example, an artist in our opening exhibition was El Anatsui, who works with waste materials such as bottle caps and employs a whole community of people who live on the street in Nigeria. By inviting them into his studio, he gives them work and helps them find a new kind of life.

ID: What was it that sent you in the direction of contemporary art?

BV: Growing up, I was always involved in the family business—entertaining clients, that sort of thing. And I was always fascinated by the art world. The experience of visiting the “Documenta” exhibition in Germany when I was 18 was the trigger point for me. I believe that contemporary art helps us see our future, while classical art tells us about experience. We need both to understand the present.

ID: Where did the inspiration for Kanaal come from?

BV: Aesthetically, from our fascination with the architecture, which has amazing proportions. Pragmatically, we were looking for somewhere to expand our business now that we have 100 employees. Conceptually, we envisioned a community for living and working that’s rooted in cultural experiences.

ID: You don’t live there yourself, however.

BV: No, I live on the 16th-century street in Antwerp that my parents restored back in the 1960’s. In a way, it was the prototype for Kanaal. All the elements are already there. Kanaal just develops them on another scale.

ID: What is it like having Axel as a father?

BV: He has always been a presence in my life. The biggest lessons I’ve learned from him are humility and the importance of being ready to do new things. If you get stuck in a rut, it’s difficult to progress in life.

ID: Could you summarize the best and worst things about working with your family?

BV: The best thing is the level of trust. The worst is the need to divide yourself between two roles with the same people—being both a family member and a coworker. That takes practice.

ID: How do you see the business developing?

BV: It’s about growing the educational role of our foundation—the gallery and exhibitions are very much about that. To make our artists more visible, to open up new possibilities for them, we have to be more visible, too. It comes down to getting the word out via curators, publishing, and so on. People will follow us in time.

Kanaal is an example of the discovery process at work. The property was an industrial waste product. No one wanted to live there. Although everyone else initially thought we were mad, we saw something in it.

> See more from the January 2018 issue of Interior Design