Frank Lloyd Wright Biography Chronicles the Iconic Architect’s Redemption in New York

After more than a decade of scandal and misfortune that encompassed murder, arson, adultery, divorce, bankruptcy, and arrest—all indiscriminately sensationalized by an often scurrilous tabloid press—Frank Lloyd Wright’s private life had chased him into a personal and professional wilderness. But the wilderness in which the architect wandered between 1925 and 1932 included New York City. And, according to a new book, the extended sojourns he spent in the metropolis during those years saved him.

Of the many Wright biographies, Anthony Alofsin’s Wright and New York: The Making of America’s Architect is unusual in focusing on the period in which the well-known, though not yet famous Midwesterner—broke, nearly broken, and vulnerable—started again from scratch. The Prairie master, who had based his career on organic design, pieced his life and practice back together in the least organic environment in America, against the improbable cacophony of the urbanism he had always deplored. Unexpectedly, New York proved curative and gestational—a crucible that helped Wright forge a second act to his career, one that would establish his relevance in a century in which he was not born and in which he had lost professional traction.

In December 1925, the nearly 60-year-old Wright, his future wife, and newborn baby—homeless thanks to a devastating fire at Taliesin, their Wisconsin residence—found refuge at the house of a relative in Queens. For the next several weeks, the architect steeped himself in the anonymity of Gotham’s crowds and the anomie of its streets. Gradually, like an amphibious creature stepping onto land, he tested the terrain, emerging from his shell of disdain and suspicion to make deeper forays into Manhattan, proving a curious and willing if reluctant explorer of what he considered dystopia.

This island of towers was the antithesis of the sprawling Taliesin homestead that had nurtured his soul, the enemy incarnate of the organic architecture at the core of his vision. Perhaps Wright considered himself a solitary genius, born full-grown on the Western plains, but the inconvenient truth was that he learned from New Yorkers. He enjoyed their camaraderie, and discovered that besides trading in money, they traded in ideas, which grew and prospered in the city’s transactional cultural marketplace.

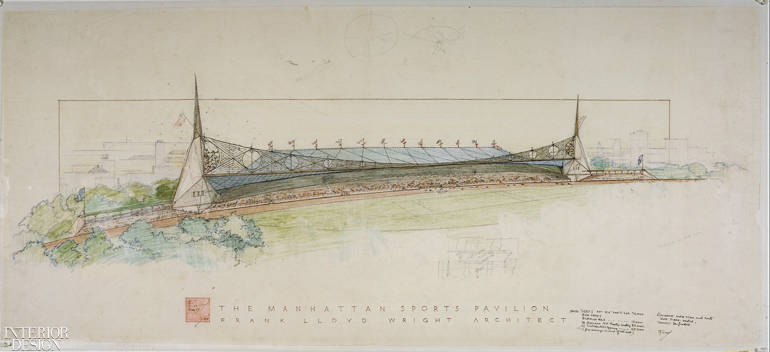

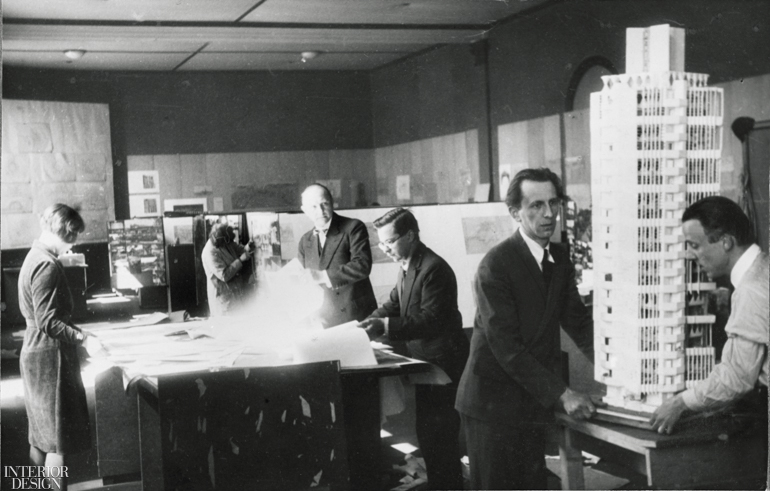

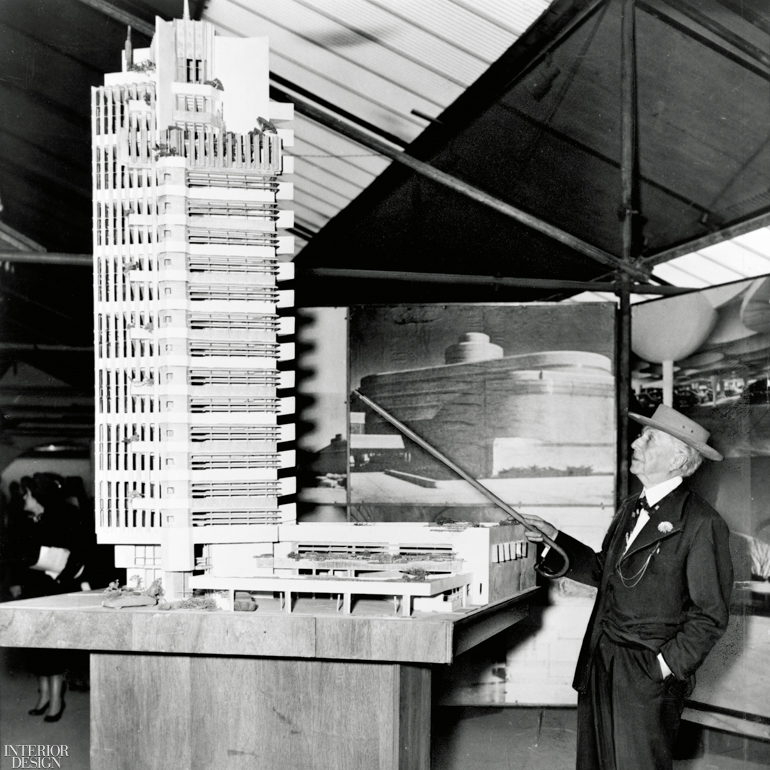

Much to his benefit, Wright drank deeply at the trough of urbanity, particularly while living in Greenwich Village for five months from December 1926, his second and longest stay in the city. He conversed with Manhattan’s intelligentsia who tested, nurtured, and matured his ideas—and subsequently transmitted them through the media: Wit-about-town Alexander Woollcott profiled him in The New Yorker; Architecture Forum and Architectural Record took up his cause; architectural historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock and urban theorist Lewis Mumford, at different times, championed him; and the charismatic Reverend William Norman Guthrie not only acted as private guide in the city’s social and intellectual labyrinth but also commissioned two designs from Wright—a vast and visionary Modern Cathedral and an apartment tower for the grounds of St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery—both unbuilt but both crucial to his

future development.

As the Prairie architect acceded to the city he at first resisted, he farmed it, exploiting its position as the capital of American

publishing. With few viable architecture projects and a sketchy income, Wright established himself as a theorist, journalist, and author who actually made a living from writing. Along with his Autobiography—begun in 1926 and first published in 1932, the longest and most important endeavor of his writing career—Wright produced more than 100 manuscripts during the period, including articles for Liberty, a mass weekly; Architecutral Record; one for The New Republic that was ultimately rejected; and several for World Unity Magazine, where he reviewed Le Corbusier’s Towards a New Architecture. The writing was remunerative and formative.

As Wright scrutinized and criticized the city and faced the gathering headwinds of European Modernism, he developed and refined his theories about building a Jeffersonian society through architecture. This culminated in The Disappearing City, a 1932 book in which he proposed reconstructing the entire country with a ruralizing vision sharply at odds, paradoxically, with the metropolis that had sustained him. It was a prelude to more than two highly productive decades of innovative design, including the Usonian houses, Fallingwater, and the

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, which celebrates its 60th anniversary this year and, as Wright’s only major New York building, stands in defiant proof that he was a leading 20th-century Modernist, though not in the boxy International Style that came to dominate the surrounding postwar Manhattan cityscape.

Hounded by the yellow press, Wright had come to New York as a sinning 58-year-old and embarked on a kind of second adolescence from which he emerged into a second professional adulthood. Freudian analysts profess that a person can defeat neurosis by breaking down a troubled personality and constructing another. Wright went through an equivalent transfiguration on the couch of the city. The collateral benefit of his polemical writings was that Wright not only resurrected his career but also mythologized himself, metamorphosing from pariah to patriarch. New York gave the architect opportunities that transformed a vulnerable, humbled figure into a Mount Rushmore–scale icon, an enduring American monument that Wright himself chiseled and shaped through his own prose.

Keep scrolling for more images >