French Architect Claude Parent’s Expressive Drawings Showcased in a New Monograph

A new monograph, Claude Parent: Visionary Architect, breaks the blood-brain barrier that has long sealed America off from French architecture in general, and from one of France’s great visionaries in particular. Claude Parent (1923–2016) never exported himself or his message. Emerging after World War II, he established a Paris-based practice that became well-known thanks to a national house competition. In 1966, Parent achieved wider notoriety when he and his partner, theorist Paul Virilio, published a manifesto, The Function of the Oblique, announcing that the horizontal belonged to classical architecture; the vertical, to modernism; but that the future was oblique. By throwing the human body into a state of constant instability, they argued, the architectural incline raises its users to full consciousness. In an overwhelmingly Cartesian culture, they posited heresy.

A new monograph, Claude Parent: Visionary Architect, breaks the blood-brain barrier that has long sealed America off from French architecture in general, and from one of France’s great visionaries in particular. Claude Parent (1923–2016) never exported himself or his message. Emerging after World War II, he established a Paris-based practice that became well-known thanks to a national house competition. In 1966, Parent achieved wider notoriety when he and his partner, theorist Paul Virilio, published a manifesto, The Function of the Oblique, announcing that the horizontal belonged to classical architecture; the vertical, to modernism; but that the future was oblique. By throwing the human body into a state of constant instability, they argued, the architectural incline raises its users to full consciousness. In an overwhelmingly Cartesian culture, they posited heresy.

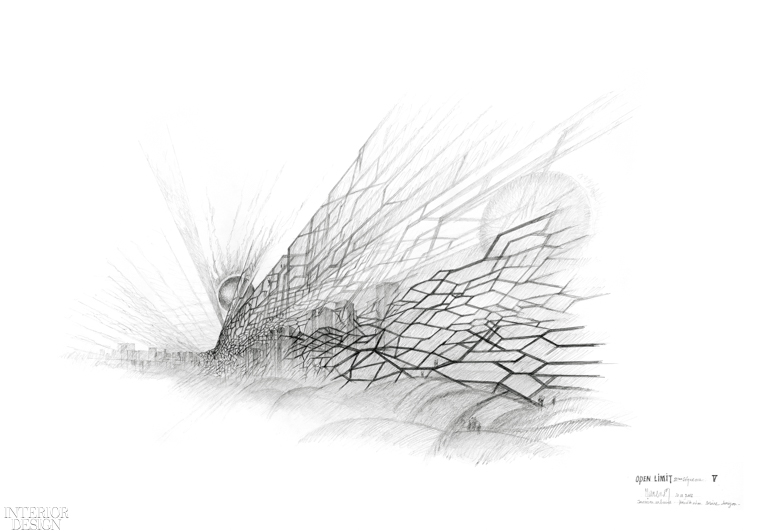

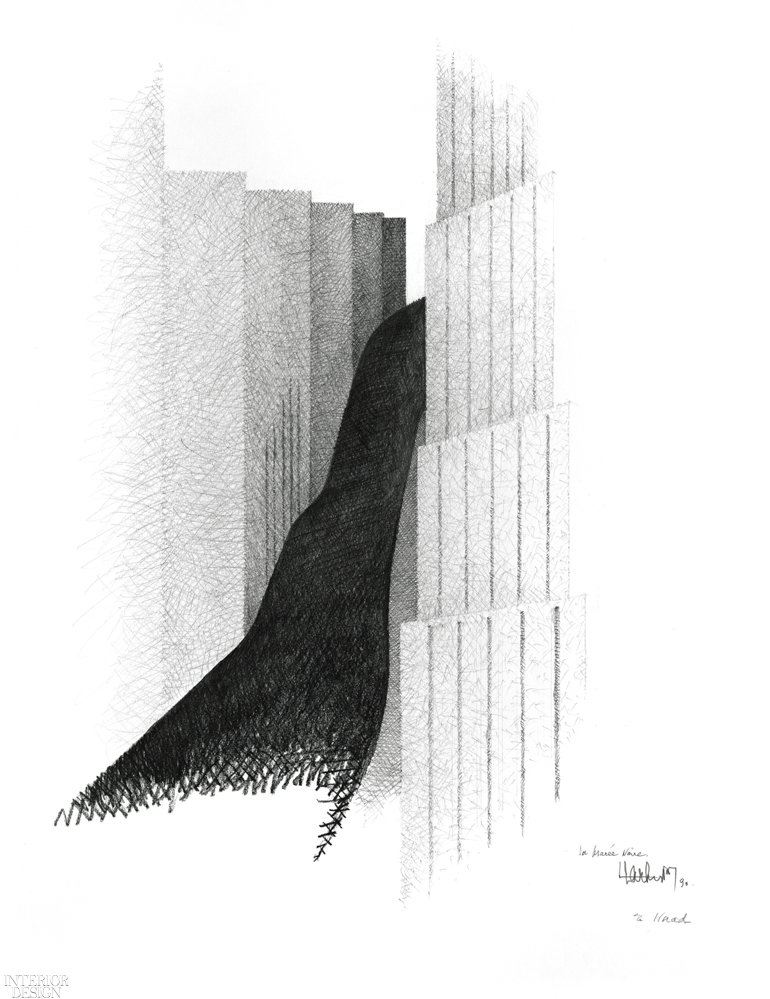

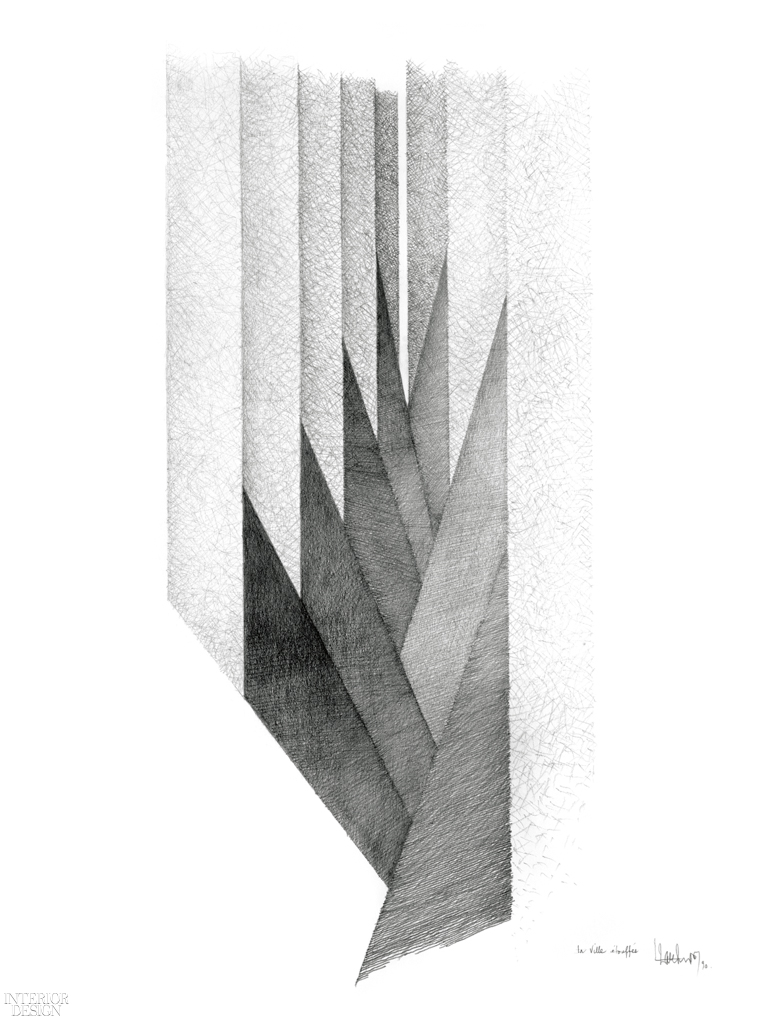

Parent explored the thesis with magisterial drawings done, counterintuitively, according to the classical drafting techniques he had mastered at the École des Beaux-Arts. This visionary portfolio of sci-fi worthy “architectural fictions” caused French architect Jean Nouvel, who worked in Parent’s office in the late 1960s, to call his mentor “the French Piranesi.”

But unlike Piranesi, whose constructed work was limited, Parent built a number of seminal projects. In 1966, he completed the startling Villa Drusch in Versailles, the living room housed in a tilted cube, poised on a single edge (although the floor inside is flat). Backed by theory, his innovative work anticipated the Deconstructivists of the 1980s (Zaha Hadid, Coop Himmelb(l)au, Rem Koolhaas, Odile Decq, Thom Mayne) and later the digital avant-garde (Asymptote Architecture, Reiser + Umemoto): Parent’s complex pencil-drawn topological fantasies prefigured their complex digital landscapes. During his long career, Parent emerged as a de facto dean of the profession in France, much like Philip Johnson in the U.S., though with a talent, integrity, originality, and vision that largely escaped the socially and institutionally powerful American.

But unlike Piranesi, whose constructed work was limited, Parent built a number of seminal projects. In 1966, he completed the startling Villa Drusch in Versailles, the living room housed in a tilted cube, poised on a single edge (although the floor inside is flat). Backed by theory, his innovative work anticipated the Deconstructivists of the 1980s (Zaha Hadid, Coop Himmelb(l)au, Rem Koolhaas, Odile Decq, Thom Mayne) and later the digital avant-garde (Asymptote Architecture, Reiser + Umemoto): Parent’s complex pencil-drawn topological fantasies prefigured their complex digital landscapes. During his long career, Parent emerged as a de facto dean of the profession in France, much like Philip Johnson in the U.S., though with a talent, integrity, originality, and vision that largely escaped the socially and institutionally powerful American.

Edited by Chloé Parent, the architect’s daughter, Claude Parent is a historically corrective monograph that introduces a major figure who should have entered American architectural literature and architecture’s international time line decades ago. The volume, which fills a serious gap, is a career narrative told as a mosaic of texts written by a half dozen architects, curators, and critics, including Frank Gehry, Odile Decq, and fashion designer Azzedine Alaïa. The short but pointed essays are interspersed with images from Parent’s prodigious oeuvre of speculative drawings, many published for the first time. (The final section comprises handsome black-and-white photographs of his buildings.) Gravity is about the only constant in architectural speculations that escape Euclidean and Cartesian geometries in favor of vast open shapes drawn at the scale of landscapes. He breaks the box at every level, including gridded cities where pedestrians walk up and down sloped ramps, their bodies awakened by the differential tugging of the earth.

That Parent, whose father was an early aeronautical engineer and amateur car designer, was partial to Lamborghinis, Rolls-Royces, and pin-striped suits masked a born radical. In early-career incarnations as a commercial illustrator working successively in fashion, advertising, and publishing, he put the tradition-bound graphic skills he’d learned at the Beaux-Arts to less-than-classical use. He even drew as a cartoonist and caricaturist.

In the 1950s, Parent started escaping architecture’s diktats by partnering with artists who introduced him to Russian Constructivism, Neo-plasticism, and Elementarism, leading him away from Le Corbusier’s Functionalism, which was then the law of the land in France and elsewhere. Parent’s drafting skills served artists as he translated their architectural ideas on paper, culminating in a 1958 collaboration with Yves Klein, who proposed making architecture out of thin air—walls and roofs, beds and chairs all shaped by pneumatic forces. Parent captured Klein’s ideas in pen and ink, as though there was nothing strange about treating gas as brick.

But after a disappointing experience at the 1970 Biennale di Venezia—he felt his oblique design for the French pavilion was not fully appreciated by the participating artists—Parent stopped acting as an amanuensis for others and began using drawing as a vehicle of his own expanding vision. He drew everything from individual buildings to entire landscapes, all featuring instability-inducing, consciousness-raising inclines.

Parent often joked that the oblique set his practice on a downward slope. It certainly limited his client base and earned him the “animosity of his peers,” as contributor Donatien Grau notes. His persistent belief in embracing the future—including the latest American ideas on retail malls and atomic energy—only increased the angle of decline. The unpopularity of several “oblique” shopping centers, which the French elite thought too commercial, and several nuclear power plants, pushed his career into partial eclipse just as the Deconstructivists emerged in the 1980s.

Later that decade, Parent was “rediscovered” by museum curator and director Frédéric Migayrou, one of the authors of the book, and then by a digital generation. Jean Nouvel based his recent, monumental Philharmonie de Paris on the oblique. He dedicated the buiding—a mountainous work shaped like one of Parent’s landforms—to his mentor. At a time of the moon walk, Parent was an intrepid explorer of a terrestrial outer space. Claude Parent is an invaluable introduction to the bravery and intelligence of this singular architectural Magellan.

Keep scrolling to view more of Claude Parent’s work >

> See more from the Fall 2019 issue of Interior Design Homes