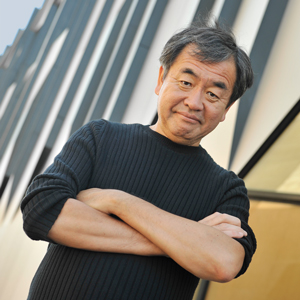

Hall of Fame Honoree Kengo Kuma Blends Traditional Techniques with Natural Materials

As a child growing up on the fringes of Tokyo, Kengo Kuma says, the building that most inspired him to become an architect was Kenzo Tange Associates’s majestic Yoyogi National Gymnasium for the 1964 Olympic Games. How appropriate, then, that for the 2020 Olympics it should be Kuma replacing the old National Stadium with a new one. Currently under construction, the stadium is poised to introduce Kengo Kuma & Associates to a global audience.

As a child growing up on the fringes of Tokyo, Kengo Kuma says, the building that most inspired him to become an architect was Kenzo Tange Associates’s majestic Yoyogi National Gymnasium for the 1964 Olympic Games. How appropriate, then, that for the 2020 Olympics it should be Kuma replacing the old National Stadium with a new one. Currently under construction, the stadium is poised to introduce Kengo Kuma & Associates to a global audience.

Kuma is admired for many reasons, not least of them the thoughtfulness of his work. For a big-name architect, he continues to design many small projects: houses, community centers, galleries, a Starbucks Coffee, and railway dining cars, even glass pendant fixtures for Czech lighting manufacturer Lasvit. He also builds extensively in remote rural Japan. When the 2011 tsunami flattened a swath of the northeast, he was quick to head up to see how he could help the recovery. He ultimately signed on to join a team designing the master plan for the reconstruction of a town.

If Tadao Ando Architect & Associates is synonymous with concrete minimalism, Kuma is the architect who relentlessly pursues the contemporary possibilities of traditional techniques and natural materials: volcanic stone, rough plaster, textured washi paper, cedar, and bamboo. When the latter puts in an appearance, as it often does, he frequently favors a yellowish species from the southern island of Kyushu. This is a man for whom the details matter.

It took Kuma a little time, early in his career, to find his architectural groove. After a year in New York at the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, he returned to Tokyo and designed a Mazda showroom that was positively baroque with the motifs of postmodernism. Those first buildings, however, seemed to get the PoMo out of his system. The pared-down style we now associate with him started to emerge.

Kuma often mentions his admiration for a text called In Praise of Shadows. Written in 1933 by the novelist Junichiro Tanizaki, it is the classic summation of traditional Japanese aesthetics. Tanizaki’s disdain for bright lights resonated with him. Diffused, dappled sunshine is a signature Kuma touch, achieved with louvers or slits.

In person, Kuma is modest and soft-spoken. His unassuming, academic air—he teaches and conducts research at the University of Tokyo and has written a number of books—belies his role at the top of two hugely productive studios with a total staff of approximately 200. The Tokyo office culminates in a meeting room and library occupying a glass box on top of a building in a fashionable neighborhood. From there, he can see the Baiso-in Temple, a 17th-century Buddhist landmark that he rebuilt. He keeps his Paris office lean with approximately 20 employees. Together, the firm is designing all over the world.

The museum lineup is particularly strong. In Japan alone, there’s the Nezu Museum and the Suntory Museum of Art in Tokyo, the Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum, the Wooden Bridge Museum in Yusuhara, and the Stone Museum and the Nakagawa-machi Bato Hiroshige Museum of Art in Nasu. In France, his Cité des Arts et de la Culture for the town of Besançon is characterized by an undulating roof and a timber-grid facade. The cliffs of Scotland inspired the V&A Dundee, a design museum that takes the form of a pair of inverted pyramids, the color of their concrete planks shifting with the sunlight. In his typically low-key way, Kuma has called the V&A a “living room for the city.”

He says that he would like to “erase” architecture altogether. Yet, as his fame grows, so do the number and size of his commissions. The biggest of the lot is the Olympic stadium, a short walk from his office. His major accomplishment is to translate the warmth of his small buildings into a large scale.

If the gargantuan size of the stadium is unusual for him, the key material is not: He proposed using native timber to represent contemporary Japan. A country with limited resources and a diminishing population, he says, should be sending out a message of sustainability. Renderings show a building with plants sprouting through its wooden latticework. Kuma might not be able to erase the built environment, but he is striving to create humane architecture that people love to inhabit.