Highlights from the Superhouse Virtual Exhibition on Italian Design in the Radical Period

Design connoisseur Stephen Markos started design platform Superhouse on Instagram at the end of 2019, a few months before the brick-and-mortar abruptly transferred into an online space. From his Brooklyn apartment, he posted about designers he admired and, as of last summer, online fundraisers to benefit anti-racism organizations. Since then, Markos’s digital background, honed through previous positions at Artnet, Christie’s, and Martha Stewart Living, has been instrumental in implementing a fully online design gallery, as well as pushing the envelope in “a website with pictures on a grid.” After a three-day pop-up group exhibition in Brooklyn last December, Superhouse has recently unveiled the virtual exhibition, Different Tendencies: Italian Design 1960-1980, dedicated to the period known as Radical in Italian design.

True to the show’s nature, the presentation challenges standards of a typical online exhibition and presents over 40 pieces through a digitally-rendered universe created by video designer, Duyi Han. “A blend of album covers, movies, and night life,” Markos shares, informed the mood board he and Han crafted after brainstorming the era’s definitive visual cues. A two-minute film swiftly follows each object within a different environment, ranging from rapidly moving escalators, boutique windows, space crafts, or night club booths. Each setting is dressed with elements that tap into this glamorous era of Italian design. The show is a personal project for Markos, similar to his initial creation of Superhouse, driven by interest for collectible design. Behind the magic, he and Han followed an intricate technical process that included taking multiple shots of each object and transforming them onto 3D renderings that fuse into the digital universe.

Read Interior Design’s highlights from Different Tendencies which lives on Superhouse’s website through May 1.

Gaetano Pesce, Up 7 (Il Piede), 1969

Subverting scales or color codes of everyday objects was a shared interest among the Radicals. Pesce, who has become something of a poster child of the movement, created this giant foot with expanding foam, an industrial technique revolutionary for its time. He coated the form with polyurethane in a ruby red hue in collaboration with C&B Italia (now B&B Italia). The company, however, never graduated the prototype for larger production. “A museum piece for sure,” notes Markos about the seating element which can be considered a sculpture today due to its unique status.

Archizoom Associati, Sanremo, 1967-8

Kitsch was a path the Radicals rarely shied away from, particularly to satirize the profile of Italy as the epicenter of “good design.” The Florence-based collective Archizoom Associati’s side lamp takes its name from the northern city, probably most famous for its annual music festival. The palm tree figure is a salute to the trees dotting the city’s tourist-laden beach on the Riviera, while the lucite used in the fonds surrounding the lamp reflects the light, in an homage to Sanremo’s festive atmosphere. The McDonald’s colors of the rails in Han’s escalator design are hard to miss, but Markos also notes the leopard print walls that contribute to the overall maximalism.

Superstudio, Quaderna console, c. 1970

Another iconic name attached to the movement, Superstudio reflected the radical spirit with a design motto that expanded the sector and aimed to blanket the everyday life—in a literal sense. The Florence-based collective, which was initially composed of Adolfo Natalini and Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, crafted a simple grid format which, according to their concept, would cover everything in the world. The idea was a critique of the effects of industrialization over rapid urbanization models and boom of generic mass production; however, this grid also became their visual trademark. They created this plastic laminate white console printed with a black grid with Zanotta, as part of a series titled, Quaderna. While the company still produces other items from the series, this early model has been discontinued. Han’s unabashedly rainbow-bursting universe surrounding the table creates an explosive contrast with the object’s mathematical color code.

Andrea Branzi, Pigiama, 1979

Similarly, Brandi was fascinated by decorative patterns and the ways they convey meaning through people donning them on attires. He, unsurprisingly, dressed a one-armed chair dressed in cotton covered with a blue and white pattern. Branzi created the pattern to resemble those printed onto mass produced pajamas. This chair was unveiled in Studio Alchimia’s first Bau.Haus collection, which included many designers that would later work in the Memphis Group. Han’s neon-lit window display puts the chair under a striking spotlight, seemingly in the late night quietness of an otherwise busy street.

Enzo Mari, Letto, 1974

While eliminating the myth around design practiced by the Radicals, Mari’s effort was particularly effective for his DIY approach to making. He created a book of simple models, titled Proposta per un’autoprogrettzaione (Proposal for Self-Planning), which would allow anyone to build their own Mari bed or table with wooden boards and a few nails. “He wanted the consumer to participate in the creation of the furniture,” says Markos. This geometric pinewood bed frame, from his Metamobile series, sits in a Modernist universe, inspired by the buildings of the Brazilian architect Lina Bo Bardi.

Gianfranco Frattini and Livio Castiglioni, Boalum, 1970

The serpentine floor lamp is another example of the designers’ interest in consumer participation. While this 81.5-inch long lamp may be used as a single item, Frattini and Castiglioni designed the PVC tube form with modular ends that can be joint to create a larger lamp. Humor, however, extends the object’s interactive nature: the duo designed the lamp based on a room keeper’s vacuum cleaner at their hotel in Capri. Han’s background design, dotted with flowers across the floor and natural light washing the hose-looking lamps puts emphasis on the product’s sculptural quality and the unexpected harmony of the PVC material with light.

BBPR, Spazio table, 1960

The Milan-based architecture firm designed a series of office furniture for Olivetti, including this desk with a PVC top. The eccentric design combines the need for modular function at an office setting with the movement’s signature avant-garde touch. The earliest piece in the exhibition, the desk is a testimony of the Radicals’ unorthodox approach to design for both domestic and public realms, as well as a humorous nod to Italy’s post-war economic boom. Han’s atmospheric universe, en par with the desk’s PVC-based form, is most notable with four nipple-like PVC suctions that elevate the desk from its legs and complete the overall aura of a Kraftwerk music video.

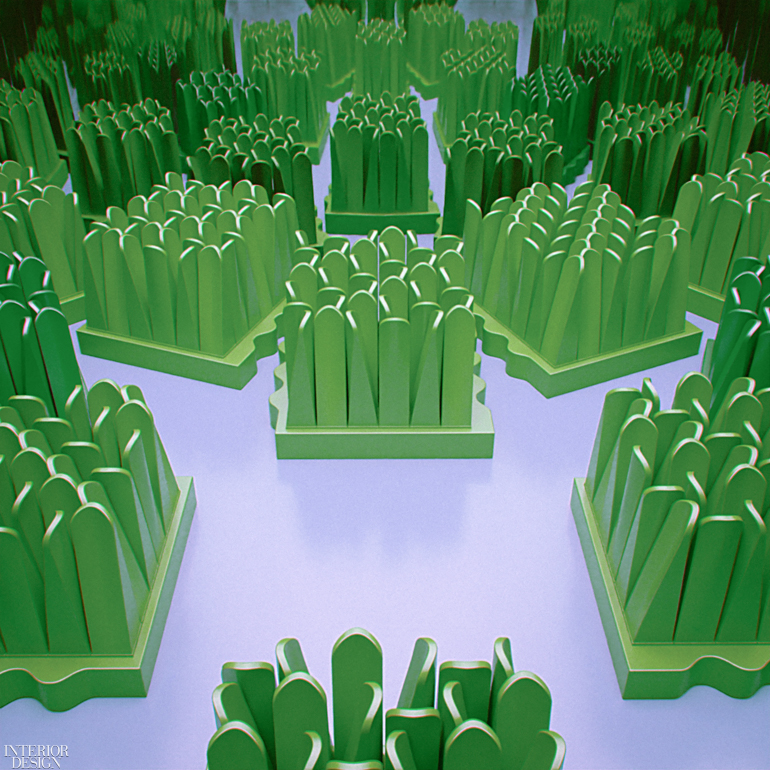

Gruppo Strum, Pratone, 1971 (from a 1986 edition)

“I don’t recommend sitting onto this edition,” notes Markos about the seat which Gruppo Strum (including Pietro Derossi, Giorgio Ceretti and Riccardo Rosso) designed using polyurethane foam hand-finished with green Guflac lacquer. The duo originally designed the seat in 1970 for a competition which they eventually won. Weighing 130 pounds, this massive “grass” is made out of forty-two blades affixed onto a base. “Ideally, you’d let yourself into the blades and they bend and hold you up,” explains the curator about the experience of sitting into one of the seats which was originally produced as an edition of 200.

Antonio Locatelli and Pietro Salmoiraghi, Centopiedi Matrimoniale 4545-6, 1972

While its single version is somewhat available today, the double bed edition of this plastic bed by Locatelli and Salmoiraghi was produced by Kartell as two separate single bed frames joint by nylon hinges. “You see the single bed once in a while, but not this one,” says Markos. The centipede reference in its name is beyond coincidental for a bed frame, upheld by twenty-four round form legs. The matrimonial element, as expected, stems from its dual structure. Humorous and light-hearted, the cloud-like form is, here, paired with Han’s own design for a mattress and tube-like pillows.

Ettore Sottsass, Svincolo, 1979

Also from Studio Alchimia’s first Bau.Haus collection, this Sottsass floor lamp may resemble a razor, but the true inspiration for its form comes from overhead lamps the designer came across on entrances and exits of Italian highways. Referencing the economic and social explosion of its time, its 96-inch high plastic laminate body also recalls marble columns as reference to Italy’s classical heritage, crowned with a metal fixture holding the neon light. The lamp is also interesting for signaling the late stages of the era, which would later be followed by Sottsass’s founding of the Memphis Group.