How Brazilian Furniture Designers Carved Out Their Distinctly Modern Aesthetic

“You are all pioneers,” diplomat Sérgio Amaral exclaimed on a recent spring afternoon in Washington. Standing in the grand drawing room of his official residence, a neoclassical mansion on Embassy Row by John Russell Pope, the soft-spoken Brazilian ambassador to the U.S. was surrounded by furniture designers, importers, gallery owners, and scholars, who had all gathered for Brazilian Design Week, kicked off with a keynote speech by Interior Design editor in chief Cindy Allen. What Amaral meant was that after almost a century, the world is finally catching up to these champions of Brazilian design, a movement that is now claiming its place in the Modernist pantheon.

Unlike its Scandinavian or Bauhaus antecedents, Brazilian modernism is distinguished by an ineffable quality known as Brasilidade, or Brazilianness. Over a luncheon of roasted salmon, the ambassador’s guests attempted to define this elusive concept so integral to the national identity. “Unpretentious sophistication,” Sossego managing partner Jonathan Durling said. “Curves, soothing corners, no harsh angularity, comfort. Life in a hammock. Life as a hammock.” Sossego, the Portuguese word for tranquility, is helping to bring the new wave of Brazilian design to North America. The furniture distributor was formed in 2015 by entrepreneur Durling after he met Aristeu Pires, a native of the state of Bahia and a former software engineer, who pivoted to a second career as a furniture designer with his 2001 rope-wrapped Gisele lounge chair; Sossego now distributes his furniture. “It’s life. It’s freedom. It’s sensual,” R & Company co-founder Zesty Meyers chimed in. He and Evan Snyderman have been instrumental in rescuing such mid-century Brazilian masters as Lina Bo Bardi and Joaquim Tenreiro from obscurity by showcasing them in their New York gallery. “If most of the world were sensual, people wouldn’t fight each other, would they?” Added Allen, “Clearly, there is a hunger for Brazilian modernism that we never knew we had.”

Guests then headed next door to the chancery, a 1971 floating black-glass cube by Brazilian architect Olavo Redig de Campos. There, an exhibition featured iconic pieces by Oscar Niemeyer, José Zanine Caldas, Sérgio Rodrigues, Bo Bardi, and Tenreiro alongside contemporary works by Domingos Tótora, Guilherme Wentz, and Pires. Standing near a Niemeyer ebonized-wood table from the 1940’s, Meyers recalled how reading a book in the late 1990’s about the celebrated architect’s work in Brasilia sent him on a 20-year quest that is far from over. “I figured if a local architect built utopia, there would also have to be local designers who could match the execution and beauty of the architecture,” he said. “And, if so, why didn’t we know of a single name from Brazil?” He and Snyderman found a few small photos in design yearbooks of custom pieces by Rodrigues and Tenreiro, but little else until a Brazilian friend sold them some chairs she had brought to the U.S. Soon after, they flew to Brazil to look for more. “It was mind-blowing,” Meyers noted. “The woods, the carving skills, the thickness, the thinness, the beauty.” In the absence of mass production, official archives, or the Internet, it took years of detective work to track down the designers and their ateliers, and to place their work in context. To Meyers’s astonishment, he discovered a thriving artisan-design scene that was largely unknown above the equator. To this day, there are custom pieces he has heard about but never seen because they remain in the hands of private owners.

Ironically, although the European avant-garde and Internationalism came to Brazil early on by way of travelers, refugees, and immigrants, and the 1922 Modern Art Week in São Paolo marked the start of Brazilian modernism, it was the country’s political isolation and late industrialization—and its homegrown hardwoods—that helped incubate a uniquely artisanal and sensual style devoid of dogma. “Aesthetically, for Brazilian designers, there are no rules,” said Durling. “In the absence of rules, anything can be created.”

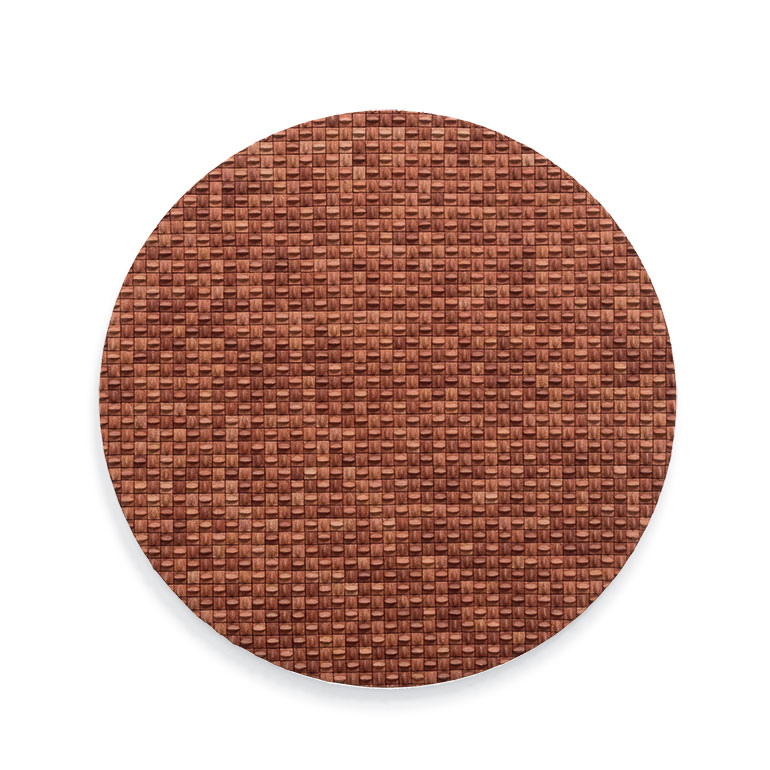

One through-line is nature. “The sinuosity of the mountains, their textures, are embedded in my work,” Tótora, a Brazilian sculptor, remarked. His home in the remote municipality of Maria de Fe, about 200 miles west of Rio de Janeiro, is surrounded by undulating hills. But with noble hardwoods such as Brazilian rosewood and Pernambuco wood now endangered, Tótora has embraced sustainability, interpreting Brazil’s curvilinear aesthetic using the humblest of materials: recycled cardboard boxes from the grocery store. He developed a laborious process to combine the pulp with soil, water, and paste; the result is molded into chunks and baked in natural sunlight, then hand-sculpted and burnished to a smooth, silky finish in the form of vases, trays, benches, and boulderlike coffee-table bases.

Tótora’s resourcefulness exemplifies what Brazilians colloquially call jeitinho, or the little way, a workaround so that life’s obstacles do not get in the way of Brasilidade. Both qualities, it turns out, are key to Brazilian modernism—past, present, and future.