Joris Laarman Lab Digitally Fabricates Exoskeletal Furniture

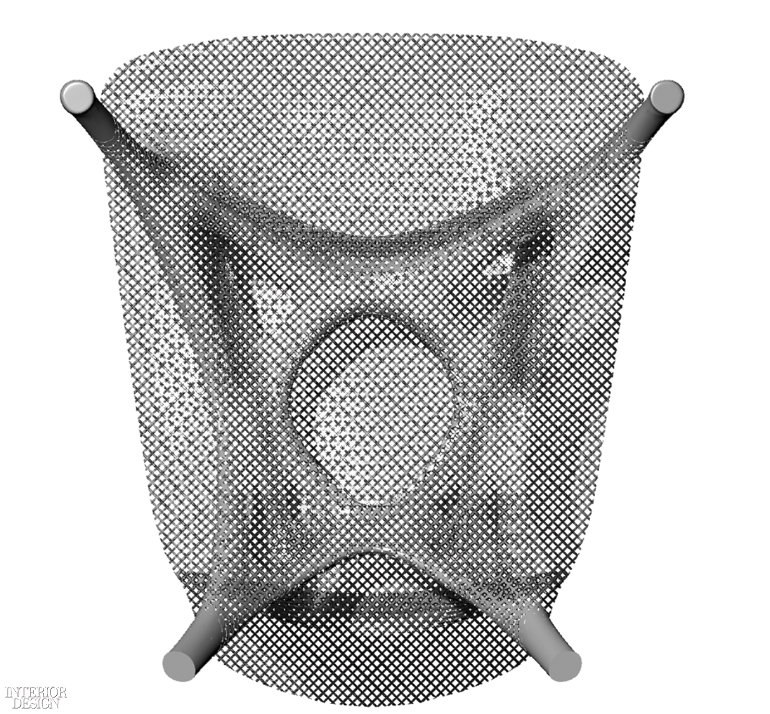

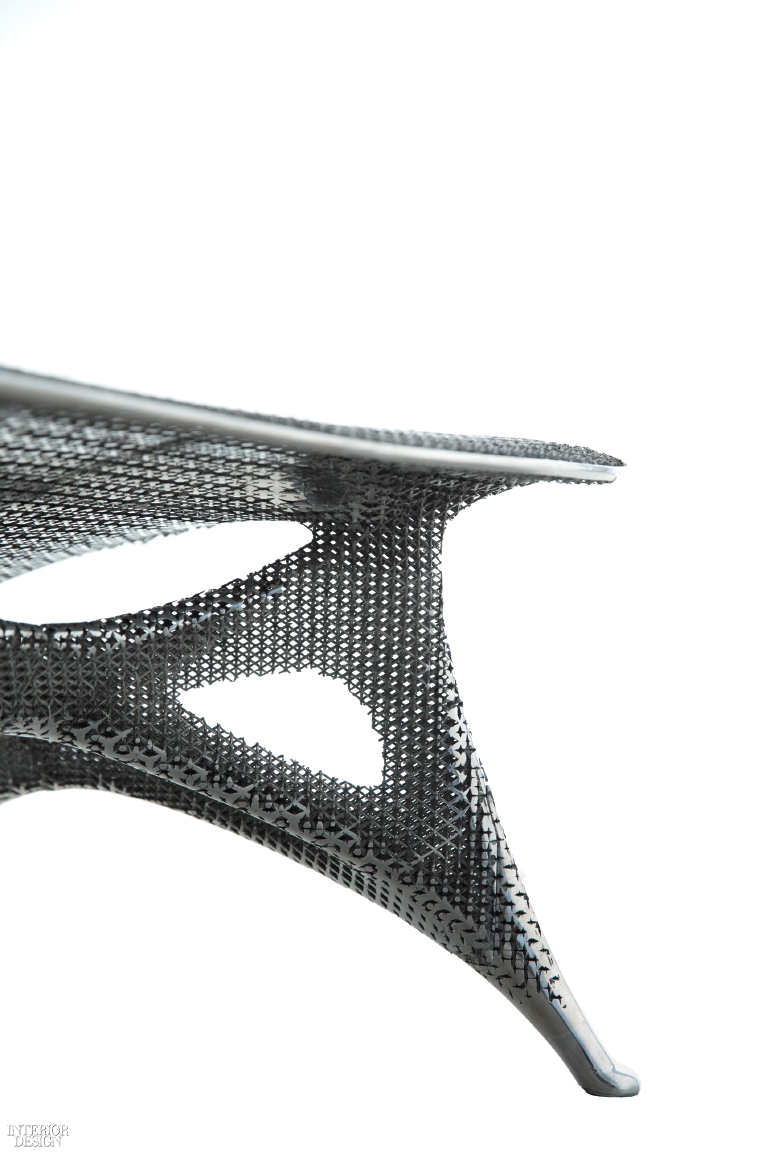

Breaking serious ground since founding his namesake lab with partner Anita Star in 2004, Dutch designer Joris Laarman first gained acclaim with a curious rococo-inspired radiator. A decadently decorative statement in the context of early-aughts minimalism, its form was in fact intensely function-driven—a dichotomy that continues to fuel Laarman’s work. “I love the multilayered quality of conceptual design, but the appreciation for exuberant curves is in my genes,” he says. More recent provocations include the Dragon bench, a tsunami of 3-D printed stainless steel, and the Gradient chair, which has a cellular laser-sintered aluminum frame to express its structural load.

Laarman’s greatest contribution to the field, though, is not a particular design so much as a new methodology, one in which technology drives form rather than simply abetting it. And now his experimental practice, Joris Laarman Lab, is the subject of a traveling retrospective. Currently on view at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, after its U.S. debut at New York’s Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, “Joris Laarman Lab: Design in the Digital Age” embraces novel digital fabrication methods. An algorithm simulating bone growth sparked an exoskeletal furniture series; cloud animation software birthed the sinuous Turkish marble Cumulus table. The lab even invents its own machines. Dragon, for instance, is produced via a welder mounted to a robotic arm used for 3-D printing. It’s a technology also being used to craft a steel bridge that will soon span Amsterdam’s Oudezijds Achterburgwal canal, creating a true fusion of past and future. The future will also include another stop for the exhibition: the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.