Kyle Bergman, Architecture & Design Film Festival Founder, Aims to Tell Real Human Stories

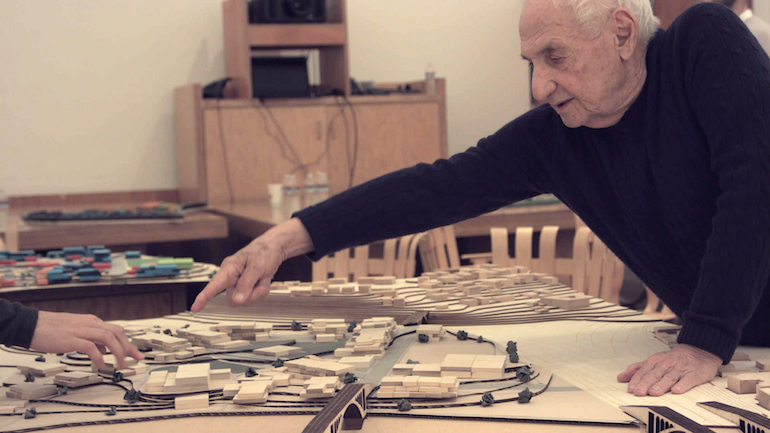

As an undergraduate, Kyle Bergman considered becoming a filmmaker before settling on his chosen field of architecture. Those parallel interests would lead him to found the Architecture & Design Film Festival (ADFF), which has grown from a small gathering in Vermont into the country’s largest film festival dedicated to the subject. ADFF bridges the gap between those two industries by selecting films that have beautiful cinematography, inspiring design, and most importantly, real human stories. Interior Design spoke to Bergman ahead of the 2018 edition in New York, which begins on Tuesday, October 16, and marks a decade since its inception. Other stops for this season include Washington, D.C., New Orleans, Los Angeles, Vancouver, and Athens, with more to be announced. The program includes films that feature Renzo Piano, Frank Gehry, and Dieter Rams, among others, along with a range of panel discussions. A full schedule can be found on their website.

Interior Design: How has your education in film complemented your work as an architect now?

Kyle Bergman: The act of making a film and the act of making architecture are similar on a lot of fronts. They’re both collaborative, they’re both a balance of art and science, and most importantly, they’re both storytelling. Architects tend to forget that what we’re doing is storytelling. As architects, we discuss light, scale, and proportion being important, and those things are also critical in filmmaking. When done well, both architecture and filmmaking are a labor of love. People do it not necessarily for the financial reward, but because they’re really passionate about it. There are a ton of similarities.

ID: What led you to the idea for the film festival?

KB: I noticed that architects are very interested in filmmaking, and filmmakers are very interested in architecture. But the bigger and more interesting component for me was, as architects, we talk to ourselves all the time. What we don’t do so well is expand that conversation. Many people don’t quite understand what we do and how we think. The festival was a great opportunity to program things that interest both the professional designer and the general public, and to bring those two worlds together. At the festival there’s a bar and café—people stay for multiple films, hang out, and have conversations. We’re creating a place where the design conversation can extend to a broader audience. That was the driving force.

ID: Is it challenging to program films that appeal both to a general audience and industry insiders?

KB: When we’re programming, our goal is to source films exactly like that. It’s not challenging, but there are some films that better suit a professional community only. The sweet spot is balancing the two. It can’t be a story about just architects; it has to have a design element, but also a human story. When I first started to think about this festival, the lightbulb went off when I saw My Architect. I loved it because it was about Louis Kahn and architecture, but it was nominated for an Academy Award because of its human story—a son’s search for his father. It bridged both worlds perfectly.

ID: Last year you showed your first feature-length fiction film, Columbus. Are fiction films something you’d like to showcase more, or was that an outlier?

KB: It was kind of an outlier. It was a fiction film, but Kogonada, the director, was thinking about architecture in a way that ventured well beyond background imagery. He was thinking about what architecture means and how we think about it. There are many great films that feature architecture, but aren’t driving at the ideas architects and designers think about. They’re great eye candy, but we’re looking for something a little deeper. Columbus had that beautiful element, but he was also talking about positive and negative space in architecture. I’m curious about bringing in more commercial films like that.

ID: What are other things you consider when selecting films for the festival?

KB: We consider the festival as a whole—what it looks like, smells like, and feels like. It’s like planning a big feast or party. For example, if there are too many biopics or monographs, maybe we save some for next year. It’s also about making sure there’s a mix and creating something fun for everyone. There should be a little bit of architecture, interior design, and environmental issues. That’s not always possible because it depends on what films are submitted and what’s out there.

ID: One theme of this year’s festival involves how design relates to social and political issues. Can you elaborate on this idea of design’s ability to improve society?

KB: I firmly believe that design can make society better. Good design helps provide an opportunity for community interaction and personal well-being. With everyone so engaged politically this year, I wanted to see if we could source films along those lines. There turned out to be several. There’s Building Justice, the film about Frank Gehry. Even Rams has a strong political statement. We’ve also been working with AIA’s Blueprint for Better films; many selected from that group have a strong political connection. Another film, called Enough White Teacups, is about Danish design awards INDEX: Design to Improve Life. We’re trying to bring in films to keep everyone socially focused and activated in these challenging political times.

ID: Dieter Rams and Frank Gehry are two designers highlighted at the festival. What about those two designers and their legacy makes them especially worthy of the spotlight?

KB: Their legacies are very different—they come from different ends of the spectrum in the design world. We all know Frank Gehry’s buildings are, whether you like them or not, very fashionable, and they work well as art architecture. The film shows Frank Gehry’s inherently conscientious and socially conscious character. On the other hand, Rams is such a purist. He’s been doing this for so long that he has a singular vision of how the world should be; anything else simply isn’t right. Towards the end of your life, it’s easier to stand by your vision.

ID: Do you program differently for a viewer more interested in the cinematic aspect than the design aspect?

KB: About 10% of our audience is from the film industry who view these films as pieces of cinema. We’re very interested in films that are cinematically great. Our closing-night film is the United States premiere of Renzo Piano: The Architect of Light by Carlos Saura, one of the most important Spanish directors. From a cinematographic point of view, it definitely falls in the caliber any general film festival. Gary Hustwit’s films, like Rams, are shown at general film festivals as well. We have another great film called Breakpoint, which is the creation myth of Lasvit. It’s a phenomenal film from a purely cinematic point of view.

ID: Have you noticed any new trends in terms of how design is represented in film?

KB: The drone shot is one major trend. Almost every one of these films has a drone shot, some gratuitous and some useful. Generally, more and more films are being made about architecture and design, which is great for the festival and the world. We now preview over 300 films, and it’s growing each year. What’s interesting is that when I first started the festival I never used the word “documentary” because I thought it would turn people off. “Documentary” is not a bad word anymore in the general public—it’s considered positive, or at least not negative. This idea of watching and engaging with documentary on all levels has helped this festival and the film world. Younger people don’t assume a documentary will be boring anymore; it could be super exciting.

ID: What did that first year of the festival look like?

KB: I originally planned to start it in 2008 in TriBeCa, but I pulled the plug because of the economy. The next year, I started it in Waitsfield, Vermont, a small town home to many architects and designers. The festival was a benefit for a local design/build school called Yestermorrow. I’m an architect, so I had never done a film festival, and it turned out to be a great opportunity to do a smaller version. It was very intimate, but we had about 1,000 people come from all over the northeast—Boston, Montreal, New York, the whole region! There had never been anything like it, and the passion for it was great to see. It was a fun four-day event that set the DNA for today’s festival. We moved to TriBeCa the following year.

ID: Has the festival’s look and feel changed as it has grown?

KB: As it grows in scale, it’s harder to keep intimate. We’re in different venues now. This year, we’re taking over the top floor of New York’s Cinepolis, a nine-theater multiplex. We try to control the lounge’s lighting and furniture to make it feel more like a design event. Having it bigger is great because more people can be involved. Despite the slight loss of intimacy, the festival has gained more energy and enthusiasm.

ID: What are some goals you have looking forward to the next ten years of the festival?

KB: We have the right size and number of days per city. Now, we hope to expand elsewhere, but it takes the right combination of people, place, and venue to give the festival the right feel and energy. One goal is to bring people together so they can engage with each other. There’s been discussion about bringing the festival online, but that’s likely not a direction we’ll take. Using this as an opportunity to bring people together is much more fun than having more people see it online.

ID: Any design films you recommend?

KB: Unfinished Spaces, which is about the National Art Schools in Cuba. It tracks the country’s buildings from the revolution to the present. There was a euphoria in Cuba around the revolution when they were first designed, but they were never completed and were abandoned. In the 21st century, people realized how great these buildings were and decided to finish them with these architects who were toward the end of their lives. It’s a story about architecture and politics, and it played at both the Miami International Film Festival and the Havana Film Festival. Those two worlds have very different ideas of Cuba, but it was loved by both of those worlds. It really told an amazing human story about politics and design.