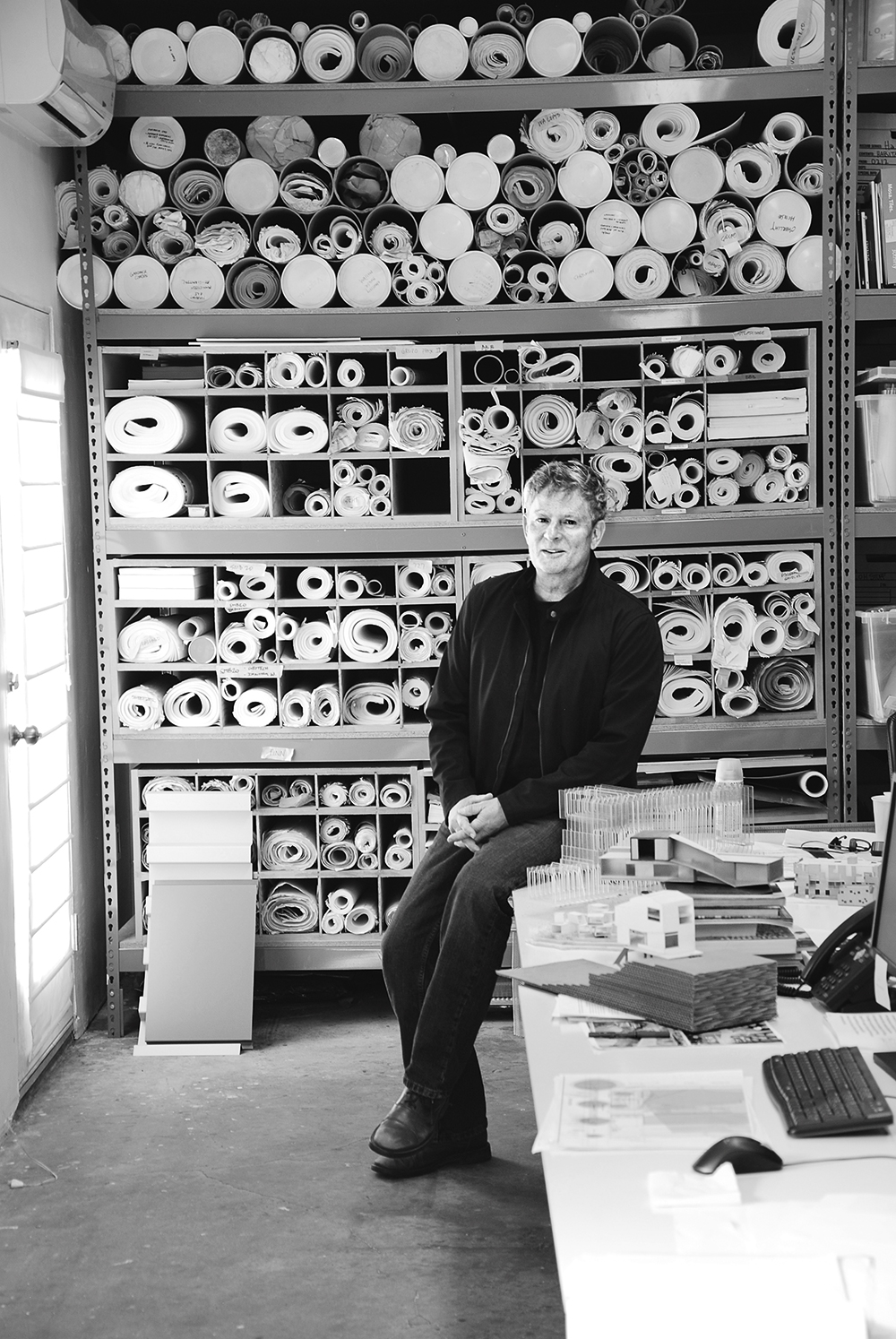

Lorcan O’Herlihy Brings Cities to Life With Bus Stops, Billboards, and Buildings

Making his architectural reputation in a classic Los Angeles way, Lorcan O’Herlihy designed clean-lined, inside/outside houses descended from the postwar Case Study Houses so rooted in the city’s hills and collective imagination. O’Herlihy, however, brought a ferocious new energy to the mid-century tradition, invigorating its thin abstractions with larger forms and bolder colors. He brought L.A.’s experimental modernism forward with big, strapping, spatially complex houses that didn’t apologize for being handsome.

He then went a daring step further, into the difficult territory of “dingbat” infill apartment buildings. Taking a typology limited by parking requirements and stucco budgets, he invented his way out of it: He unpacked the standard formula via sectionally complex apartments with an inside/outside porosity borrowed from his houses. Following a striking, career-making building next to Rudolph Schindler’s house, now the MAK Center for Art and Architecture, O’Herlihy designed a series of projects that are sculptural, graphic, and geometrically crisp, many with stepped massing. Often clad in brightly painted industrial metal and mesh, they are gifts to the street, tableaux of abstraction, some with a filmy delicacy and others robustly quilted.

His identity as an Angeleno architect was nevertheless deceptive from the very start. He was born in Ireland, the son of Academy Award–nominated actor Dan O’Herlihy, and spent years as a painter, whence his smart eye, before working on the Musée du Louvre in Paris with I.M. Pei & Partners and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York with Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo and Associates. Now Lorcan O’Herlihy Architects is casting its net coast-to- coast, with educational, cultural, and civic work that is bringing him into a more public realm. Back in L.A., that includes two unique curbside projects: bus stops in Santa Monica and billboards on Sunset Boulevard.

Could you describe your approach for the bus shelters?

The Blue Bus has been around for years, and the uniqueness of that traveling color contributes graphically to the brand of Santa Monica. To encourage ridership, especially among younger folk, the city hired us to extend the program to provide shade and seating. The limited budget didn’t allow for a conventional structure on all 300 sites, so we developed a kit of parts that can be adapted, giving each stop an identity of its own and a sense of place.

Simple, flat disks—in blue, of course—come in three sizes. We put the bigger disks, equipped with solar panels, on top of steel poles for shade and used the smallest disks as seats. We clustered as needed, not geometrically. It’s urban acupuncture.

How did you turn a billboard into architecture?

The billboard is a local cultural tradition, especially on the Strip, but the standard structure is not architecturally designed. I started by thinking about seeing it from an approaching car. Because Sunset Boulevard goes east and west, there needed to be two billboards, each angled at oncoming traffic. They’re connected to a shared support with a fluid wishbone gesture. We found an oil-pipe fabricator that could bend massive steel tubes at their nodes to form a continuous curve.

I think of the project as an urban installation. It cost about 20 percent more than a conventional billboard, and that cost gets passed along to the advertisers, but we just got a call from Google, asking to promote its Nest smart-house system there. Good design pays.

Given your interest in structures with a strong public presence, what’s the attitude of your buildings to the street?

What’s missing in a privatized place like L.A. is an engagement with the public. I try to break down that barrier by designing buildings with active edges that engage the sidewalk in a dynamic relationship, cultivating a rapport beyond the property line. Building materials are critical, and with challenging budgets we often use off-the-shelf or repurposed materials, intended for other applications. For example, fluted and perforated metals provoke dramatic plays of light and shadow in the California sun.

Have you found any significant differences between working in L.A. and other U.S. cities?

Most of our projects in L.A. have been infill. In Detroit, we’re now designing for enormous open spaces. We’re doing four mixed-use buildings that are the cornerstones for creating a large residential community in the Brush Park Historic District. Another project, the Dabls MBAD African Bead Museum, is an arts-and-culture campus that’s woven into a series of rehabbed town houses and includes murals intended to serve as beacons to the community.

In L.A., we stitch new construction into the existing fabric. The challenge in Detroit is to radiate beyond the property, to encourage and set the scene for further development. We’re catalysts for renewal at an urban scale.