LTL Architects: 2019 Interior Design Hall of Fame Inductee

The defining moment, professionally and philosophically, for David J. Lewis, his identical twin, Paul, and Marc Tsurumaki came in 1997. The three, in their early 30’s at the time, were living in New York City, working day jobs for Peter Guggenheimer Architects (David), Diller + Scofidio (Paul), and Joel Sanders Architect (Marc), as well as teaching at Cornell University, the Cooper Union, and Parsons School of Design, respectively. But in their spare time—“between midnight and 4AM,” Tsurumaki recalls—they were collaborating on speculative projects.

Then came a big break. The year before, Paul Lewis and Tsurumaki had designed a pair of exhibitions pro bono for the Storefront for Art and Architecture in downtown Manhattan. Storefront’s founder, Kyong Park, returned the favor by offering the two architects, now joined by David Lewis, to exhibit their work at the gallery while it was empty over the summer. “Of course we said yes, but we had nearly nothing to show. So we spent four months generating 10 projects—an illusory body of work,” Tsurumaki continues. He and the two brothers then produced it in the context of an academic argument, which they further refined and committed to print.

“It’s what galvanized LTL Architects, which hadn’t existed yet in any real form,” David Lewis adds. “And it was also the inception of our process.” The foundation of the story of Lewis.Tsurumaki.Lewis, as the firm was originally known, exemplifies what has, for 22 years, been the firm’s driving philosophy: The problem is the generator of the solution. Yet if LTL derives its ideas from a project’s constraints, their work is equally characterized by, Tsurumaki says, “a combination of pragmatism and invention”: a journey from the rational to “the imaginative, the extraordinary, and, in some cases, the surreal.” Indeed, the architects frequently resolve problems by exposing them, as with Poster House, New York’s first museum devoted to poster art. To maintain the openness of the existing architecture while creating climate-controlled exhibition spaces, LTL nested the galleries within the larger context like, Paul Lewis says, “a ship in a bottle,” forming a dynamic interchange between two conflicting conditions.

The outcome—perhaps surprising for this relentlessly brainy trio, who met while Paul Lewis and Tsurumaki were earning their master’s in architecture at Princeton University (David was at Cornell for a master’s in history, then received another in architecture from Princeton)—is often purely joyful. The design for the Helen R. Walton Children’s Enrichment Center, an early-childhood facility in Bentonville, Arkansas, “looks completely irrational,” David Lewis says, “but is the logical play-out of a set of clear expectations,” including single-story construction and direct access to outdoor areas from each of its 21 classrooms. Following the rules produced, Paul Lewis notes, “this unanticipated geometric dynamism is at the heart of the building—the play of the rational pushed to the point of delight.”

The firm works in every architectural genre—hospitality, residential, cultural, and, their primary focus, education, including recent buildings for Cornell, Columbia, and New York Universities—applying the same pragmatic-to-magical methodology. Yet while all projects receive equal attention from all three principals, unlike many multi-partner firms, in which the work is divvied up, they admit to a preference for projects, David Lewis says, “that engage a collective. Architecture has the potential to foster community in direct terms, to have a positive impact on the largest number of people.” Adds Tsurumaki: “The broader the public is, the more rewarding the project can be.”

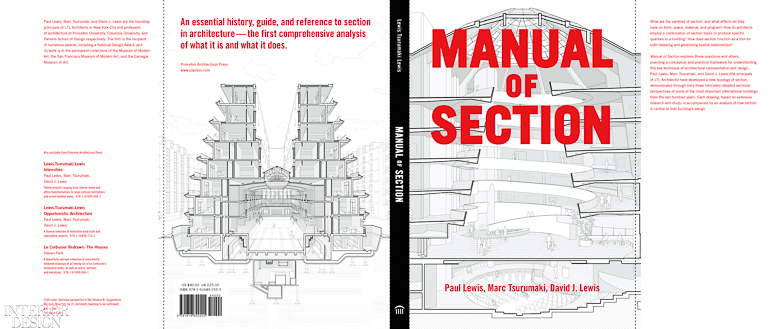

Given the firm’s iconoclasm, it’s unsurprising that, when asked to name its most important projects, the answer includes one that was never meant to be built—a design for New York Harbor that responds to the effects of climate change, created for “Rising Currents,” a 2010 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art—and Manual of Section, a 2016 book devoted to understanding buildings via their section drawings. Also on the list are micro-budget Manhattan restaurants from the early 2000s, such as Tides, which, at 420 square feet, demonstrated LTL’s ability to overcome space constraints via unorthodox materiality, in this case, a ceilingscape of thousands of bamboo skewers, and the Contemporary Austin, a nearly 24,000-square-foot Texas museum resulting from adaptively reusing an old building. “We incorporated the preexisting historic architecture and also strategically reinvented it,” Tsurumaki explains. “It expresses our problem-into-solution sensibility.”

For a small office, which varies in size from 12 to 20 employees, LTL has proved remarkably prolific: producing 130 projects, with 11 more on the boards, while developing a reputation for meticulous visual representation, and for demonstrating the viability of their ideas by custom-crafting prototypes and material studies. “The studio is a true collaboration, working together on the design aspect of every project,” Paul Lewis says. “We often talk about it in terms of paradox,” Tsurumaki adds. “We explore the contradictory conditions in each project and allow them to engage with one another.” The experience—and the work—that emerges is all the more rich.