Michael Graves Remembered For Colorful Historicism and Healthcare Innovation

Last week saw the passing of two giants of architecture— Frei Otto and Michael Graves. While Otto, who was posthumously announced as the recipient of this year’s Pritzker prize, is remembered as an architect ahead of his time for his pioneering design of lightweight structures, Graves’ colorful brand of historicist architecture had its admirers and detractors.

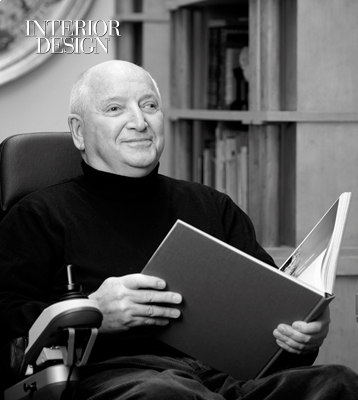

Photo by Barry Johnson/Michael Graves & Associates.

A lapsed member of the avant-garde New York Five—Richard Meier, John Hejduk, Charles Gwathmey, and Peter Eisenman rounded out the group in the early 1970s—Graves generated controversy not only by abandoning Modernism, but by taking Post-Modernism to its kitschy nadir with his designs for Disney in the late 1980s that included hotels topped by giant swans and dolphins, and corporate headquarters featuring the Seven Dwarfs as architectural supports much like Greek caryatids.

But Graves’ admiration of the ancient world and history was genuine. Roman antiquities, Biedermeier furniture, and reproductions of Romantic paintings filled his Princeton, New Jersey home. And while in recent years his practice, Michael Graves & Associates (MGA), tended to work on more institutional and hospitality-oriented buildings rather than the big cultural commissions, during that time Graves revolutionized a different type of design.

In 1985, high-end Italian housewares line Alessi introduced Graves’ now iconic whistling-bird tea kettle, which remains the company’s top-selling product. According to Alberto Alessi, “Michael Graves has been for Alessi one of the leading authors and design heroes. I’ll never forget his contribution to our history.”

In 1998, Graves began a 15-year relationship with Target, and what became known as the “democratization of design.” His work for the American retailer—which included tea kettles, toasters, colanders, coffee pots, alarm clocks, and dozens of other household items—not only made design affordable to the masses, but led to a generation of fashion and design partnerships that have benefited both retailers and designers.

“He cared deeply about architecture, which he saw as an ongoing conversation with a history that was still very much alive for him”

Earlier this year, MGA was selected as one of Fast Company’s 2015 Most Innovative Companies for “tackling design backwaters with empathy and fresh ideas.” Confined to a wheelchair since 2003, Graves addressed problems related to healthcare design with products ranging from innovative wheelchairs and fashionable walking sticks to soothing hospital furniture and high-contrast signage for the visually impaired.

Graves was also an educator. In four decades at Princeton University, he taught or influenced thousands of students. In a post on the School of Architecture’s website, acting dean Stan Allen called Graves’ impact on the field enormous. “He will be remembered for his seminal contributions to the rethinking of the Modernist canon of the 1970s, and the sea change that was Post-Modernist architecture. He cared deeply about architecture, which he saw as an ongoing conversation with a history that was still very much alive for him.”

A portion of “Past is Prologue,” a retrospective of Graves’ 50-year body of work at Grounds for Sculpture in Hamilton, New Jersey, has been extended through April 12. A memorial service will be held at Richardson Auditorium at Princeton University on April 12, 2015 at 1 pm. For more information visit http://michaelgraves.com/memorial .

What follows is an interview with Graves that Interior Design published in October, 2014:

Interior Design: Tell us about your office today .

Michael Graves: The staff totals 50, and headquarters is two 1800’s houses. One is for architecture, the other product design. I’m on the products side, because there’s a ramp for my wheelchair.

ID: What building projects are you working on?

MG: In partnership with Kean University in Union, New Jersey, we’re designing an architecture school for Wenzhou University in China along with a master plan for the campus. We’re also doing a resort in Lausanne, Switzerland, and a mixed-use project in Sri Lanka.

ID: And for products?

MG: I’m doing five pieces for Stryker, including a transfer chair, which is a wheelchair pushed by someone else. I have a new client that I’m designing home health-care products for—I can see them being marketed in a place like Target. I started de-signing products in college, by the way. I designed all the furniture for my first apartment.

ID: You work at many different scales. Do the design processes differ?

MG: Most designs start out with a drawing either in my sketchbook or at my drafting table. An architect draws to remember. I do referential drawings, whether in Italy, France, or Princeton. I went to school before computers, so we drew everything.

ID: Do the drawings differ by project type?

MG: Not all that much. I generally have a reference point. For instance, a grandmother asked if I’d design a tree house. I said yes—it would be like making a house in the sky. Most tree houses are made of wood, and mine would be, too, but it would look like one of the great Swedish tents.

ID: You were a Rome Prize recipient. What are influences from time spent there?

MG: Italy has been everything. I wasn’t really educated until I saw Rome’s architecture, from Vitruvius through Palladio. I remember those wonderful walks after dinner, the passeggiate. That’s when I got interested in urbanism—the streets, the buildings coming out to the sidewalks, the shop windows. That doesn’t happen so much in 20th-century architecture.

ID: Does your postmodernism have its roots in Rome?

MG: My break from modernism wasn’t an aesthetic idea. It was more about moving to something more humanist.

ID: Would you discuss how paralysis has affected your professional life?

MG: It has brought health care into our practice. Being an architect, a designer, and a patient, I have a special awareness for, say, how the hospital bathroom should be. Now breaking ground in Omaha is our Madonna Rehabilitation Hospital catering to kids, and that’s exciting for me. The mock-up patient room is everything I wanted and more—wood cabinetry and flooring, space for family to stay over. There’s life.

ID: What is the Wounded Warriors Project?

MG: We’re designing and building prototype houses for the families of disabled soldiers as they continue to serve at Fort Belvoir, Virginia. The first soldiers to move in were amputees. One wanted to cook, so there’s a counter that moves up and down hydraulically. Also, amputees and paraplegics generally don’t have good circulation, so we put in nine individually controlled temperature zones. And we made hallways extra-wide to allow two wheelchairs to pass each other or turn 360 degrees. That’s something, by the way, I can’t do in my own house.

ID: What would you like to do that you’re not doing?

MG: The next project! I like to stay busy. If it’s a hospital, so much the better.