Parrish Art Museum Explores Architecture’s Relationship With Photography

Garry Winogrand, the renowned photographer of American life, once observed: “Photography is not about the thing photographed. It is about how that thing looks photographed.” Winogrand was expressing a view that could be ascribed to many architectural photographers, who are, at least in some cases, less interested in recording how buildings look than in producing images of how they could, or should, look. In so doing, they sometimes join forces with architects, who wish to disseminate idealized images of their work, and with publications that waver between wanting to present reality and wanting to offer visual delight.

The gap between documentation and manipulation is a central theme of “Image Building: How Photography Transforms Architecture,” an exhibition at the Parrish Art Museum—itself, the occupant of a much-photographed Herzog & de Meuron structure—in Southampton, New York, through June 17. It includes images that make no claims at realism—some by current art world darlings such as Thomas Ruff, who has said that other photographers “believe to have captured reality and I believe to have created a picture.” Therese Lichtenstein, the show’s curator, notes in her catalog essay that Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron once commissioned Ruff to photograph their buildings to see, she says, “what they would look like as art.”

Prominent among the photographs that make no attempt at “accurate” representation are works by Hiroshi Sugimoto, who renders famous buildings in blurry black and white. In a 2001 image, for example, he strives to see how far he can distort 30 Rockefeller Plaza without sacrificing its recognizability, a process he describes as “erosion-testing architecture for durability.”

For Sugimoto’s images to work, the subject buildings must already be iconic—a status they acquired largely through the efforts of his camera-wielding predecessors. The narrow-shouldered 30 Rock, for instance, was made instantly recognizable in the 1930’s by Samuel H. Gottscho. But even Gottscho, it turned out, was a manipulator who shot 30 Rock first with enough light to get the skyscraper’s outlines sharp, and again by night, to capture the glow from its windows, then combined the results in the darkroom.

“Documentary” photographers who didn’t resort to such extreme efforts still took pains to shoot modernist buildings in ways that made them look glamorous. As Interior Design Hall of Fame member Julius Shulman once stated: “Every architect I’ve ever worked for has become world-famous, because of the publicity they get.” Shulman himself is famous for shooting the Case Study Houses, the mid-century Southern California experiments in residential design, sponsored, tellingly, by a magazine.

Shulman’s postwar contemporary Balthazar Korab photographed tightly cropped sections of buildings, creating abstractions from the architecture of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and other masters. Today, Korab’s closest counterpart may be Hélène Binet, whose work zeroes in on forms and textures, sometimes making it a challenge to determine what exactly is being depicted. (Luisa Lambri and Judith Turner, neither of whom is in the Parrish show, explore similar effects.)

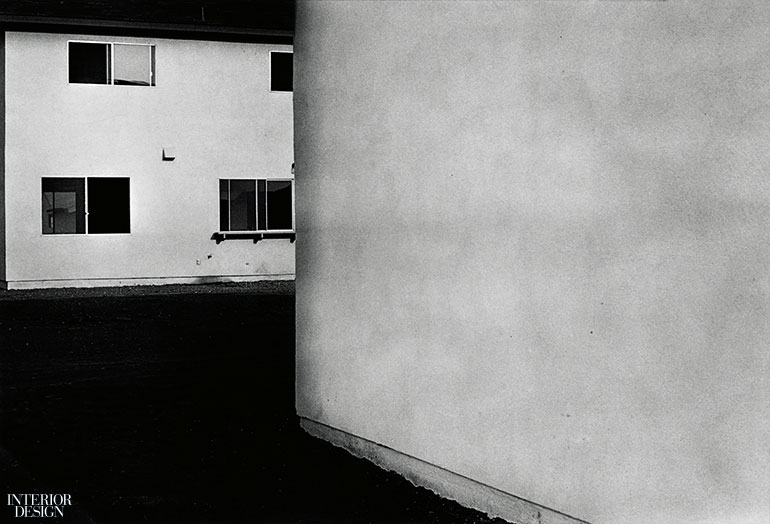

One divergent strain in American architectural photography has been the dystopian vision. A case in point: Lewis Baltz’s 1970’s images of the tract houses in the West, which make the buildings seem, in Lichtenstein’s words, “outmoded even before their completion.” While photographs like these populate art journals, they are less likely to turn up on the pages of architecture or design magazines, where they may be seen as downers.

Architectural photographers must decide whether to include people in their images. Contemporary German conceptualist Candida Höfer believes photographing buildings with no one in them reveals a lot about human nature, just as an absent guest is often the subject of conversation at a party. The young Dutch photographer Iwan Baan tends to include people in his shots, but not always the people the architect or the client would have chosen. He gained prominence last decade documenting the construction of the CCTV headquarters in Beijing by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture with his images that placed migrant workers and their makeshift living quarters in the foreground.

For a century, photographers of architecture and interiors have been a mainstay of print media, including general interest publications. Gottscho’s work appeared regularly in Town & Country as well as the more specialized House & Garden, while Ezra Stoller published in Look, Harper’s Bazaar, and Playboy, along with the expected architecture journals. Design magazines play a hybrid role, not only entertaining but also educating readers, and thus tend to stay on the “representational” end of the spectrum (with “misrepresentation,” for art or profit, at the other end).

But, as a show like “Image Building” makes clear, there is no such thing as pure representation of buildings in photographs. The qualities of great interiors, especially, must be experienced first-hand. As Baltz said in a 1993 interview, “Architecture, real architecture, always defies reduction into two-dimensional representation. If not, it’s hardly architecture at all.”