Remembering Ettore Sottsass on His Centennial

A visionary who was born in 1917 in Austria and passed away in 2007 in Milan, Ettore Sottsass left an influential but polarizing legacy. So his centennial provides an impetus to gauge the abiding relevance of this architect and designer

of furniture, ceramics, jewelry, electronics, and graphics not to mention painter, photographer, writer, and traveler. With “Ettore Sottsass: Design Radical,” running at the Met Breuer in New York through October 8, and the reissue of a 492-page tome by Philippe Thomé, published by Phaidon Press and titled simply Sottsass, we have both a physical landscape to traverse and a map to guide us. And we do need that map, because Sottsass, an intellectual who studied anthropology, ethnology, archaeology, geography, philosophy, linguistics, and quantum physics, was nothing if not complex.

His life presents itself as a richly creative journey—a long, strange trip, perhaps. He began his career steeped in modernism gleaned from his architect father, who trained in the Vienna of Otto Wagner and Adolf Loos. The brand of rationalist modernism associated with Loos, as well as early polemical Le Corbusier and the Bauhaus, proposed a complete break from the forms and associations of the past, advocating an “essential” geometry characterized by a complete lack of ornament.

To that background, the younger Sottsass added an aversion to institutions, hierarchy, authority, and dogma, courtesy of his exposure to fascism during World War II. His postwar path was punctuated by a series of libidinous activities and professional fresh starts. A stint in New York at George Nelson Associates in 1956 was followed in 1961 by a formative trip to India, where he absorbed ancient wisdom and the explosion of color. Then came a decade-long detour through the nonconformist, quasi-mystical, pharmacologically enlightened beat-generation and hippie counterculture, ultimately leading, via participation in the Italian “counter-design” movement epitomized by Archizoom and Superstudio, toward the 1980 founding of Memphis, that transgressive affront to conventional good taste.

Memphis would not be the end. Sottsass Associati continued designing products for manufacturers, limited-edition glass and ceramic vessels, and residences for well-heeled clients. However, Memphis would be, if not a culmination, then a cynosure with immediate and lasting connections to both high and popular culture.

“The graphics came in through the back door of fashion, television, and media—

Air Jordans, Miami Vice, and even McDonald’s, which used his Bacterio pattern of laminate to decorate their restaurants,” Jim Walrod says. (Besides working on interiors at Jim Walrod Design, he has been a Memphis collector for 20 years.)

Bauhaus-driven functionalism became a primary target for Sottsass’s arrows, along with the Gesamtkunstwerk type of coordinated design, which apparently vexed him. After giving his 1970’s furniture compositions for Studio Alchimia the facetious name Bau. Haus, he cheerfully proclaimed, “You can place them almost anywhere. They don’t ‘go’ with anything anyway.”

As he saw it, his task in questioning, challenging, and shaking up the status quo was to expand the definition of function to embrace psychological, spiritual, emotional, sensory, and erotic functions, represented by his priapic vases and totems. He aimed to invest objects

with artistic expression, symbolic

meaning, and visceral impact, to reconnect design to cultural memory and everyday ritual. That might mean archaic archetypes and associations on the one hand and, on the other, contemporary “outsider” sources such as the urban street or suburban diner. Classical forms might be modified with unexpected and disorderly color combinations and additions. A barbarian at the gate, he pictured a jolt of vulgar vitality reinvigorating an effete empire.

It is worth noting that he didn’t really consider himself an iconoclast or a postmodernist. His rebellion was a sharp poke in the ribs, not a knife in the heart. Indeed, he spent a good part of his career working within the industrial system with Bitossi Ceramiche, Poltronova, Olivetti, and later Alessi, actually getting objects into production while achieving an astonishing amount of artistic license and control.

Imagine a cross between George Nelson’s Comprehensive Storage System and Joseph Cornell’s boxes, and you’ll be able to picture Sottsass’s “wall compositions” from 1957. His first experiments with slatted and striped cabinets for Poltronova, 1958, shared with the American modernist “Good Design” of the same period a sculptural elegance, a restrained flair. Photographs of his own Milan apartment at that time show a meticulously composed, brilliantly edited arrangement of potentially disparate elements creating a dynamic, abstract whole.

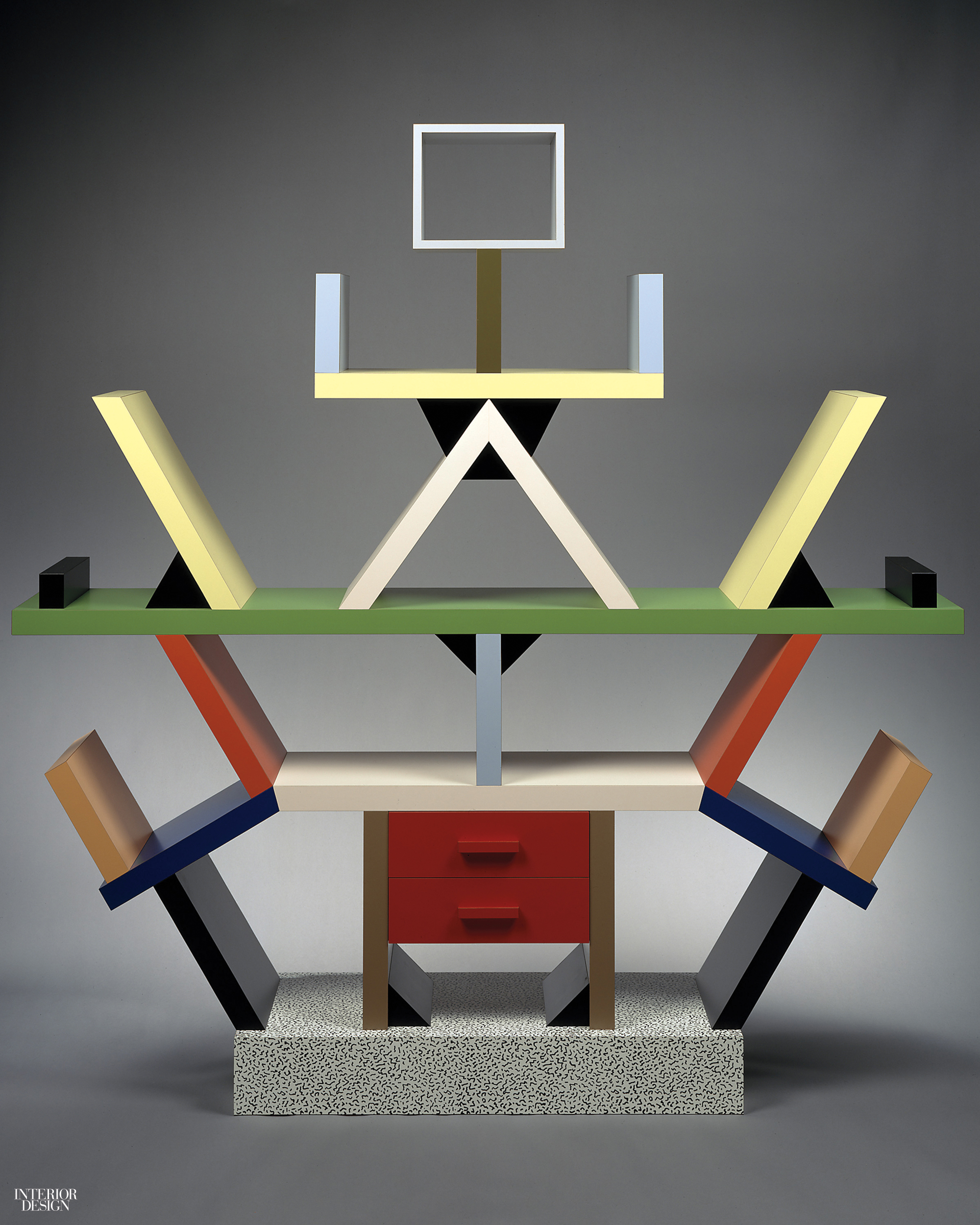

The apartment points to “collage” as key to his visual language, foreshadowing Memphis. To some, the unprecedented assemblages of colors, shapes, patterns, and materials of Memphis were childish and self-indulgent. To others, it was joyously liberating, opening up avenues for expression by upending the certitudes of orthodox modernism and instead embodying randomness, chaos, and mutability. Sottsass proposed that design offer possibilities, not solutions. His iconic Carlton shelving unit or room divider of 1981 thus stands as a sort of quantum-physics uncertainty principle—with drawers.

Memphis broadcast to an international audience Sottsass’s most revolutionary and ultimately influential idea: Design could serve as a vehicle for direct, uninhibited communication. His relevance today can be measured not only by the amount of attention he continues to receive—the books and the exhibitions—but also, for better or worse, by drawing a line from Memphis to Twitter.