Sam Maloof: Requiem for a Woodworker

First posted the week after Maloof passed away in 2009, as a tribute to him and a meditation on craftsmanship. The thoughts resonate again with the passing in January of Wendell Castle—another link in the chain.

“The hand of man touches the world itself, lays hold of it and transforms it…The artist, carving wood, hammering metal, kneading clay, keeps alive for us man’s own dim past, something without which we could not exist…In the artist’s studio are to be found the hand’s trials, experiments, and divinations, the age-old memories of the human race which has not forgotten the privilege of working with its hands.” — Henri Focillon, from “The Life of Forms in Art” (1942)

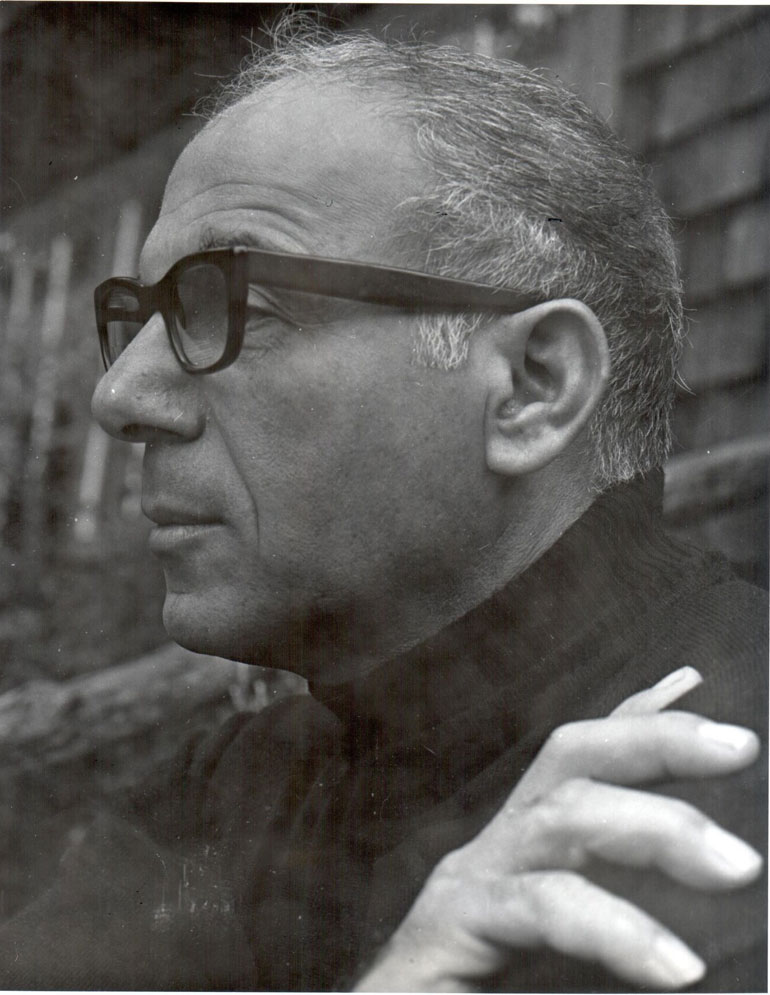

With Sam Maloof’s passing at age 93, America lost one of its premier craft woodworkers, and a solid link in a chain stretching back through history. Maloof understood and appreciated the privilege of working with his hands, and of living the way he saw fit. For Maloof, the smell of wood and the satisfaction in making a good piece of furniture, the joy in creating and then in giving pleasure to others, formed the basis of a rewarding and meaningful life. Humble and gracious, he referred to himself as simply a woodworker, though of course he was more than that. During a career that spanned six decades, he became a living argument for the vitality and relevance of the designer-craftsman.

Maloof began his career as a furniture maker shortly after WWII. According to Michael Stone, author of “Contemporary American Woodworkers” (1986), Maloof typified this generation of craftsmen—self-taught and fiercely independent, they were forced to create their own market for handmade furniture. Maloof never forgot the financial difficulties he faced when starting up, nor the absence of role models. By all accounts, he was generous with his time and energy, encouraging young artisans, performing lectures and workshops, and diligently advocating and promoting craft causes. Gerard O’Brien of Reform Gallery, who befriended Maloof in the past decade, emphasizes Maloof’s activism, suggesting that he helped bring cohesion to the American craft movement.

Maloof stated his design philosophy succinctly: “My goal is to make furniture that people can be comfortable living with. If you’re not preoccupied with making an impact with your designs, chances are something that looks good today will look good tomorrow.” Structural and visual durability were the essence of Maloof’s craft—he built things to last, from artful and sturdy joints to classically simple forms that he refined and improved over time. Rather than chasing novelty, Maloof mined a finite number of designs that became idiomatic for his oeuvre and iconic for American craft. By varying his themes and building by eye and feel, Maloof produced a rich diversity in his output.

As he noted, his pieces all differ a little bit. Maloof’s most popular designs—and the ones for which he will best be remembered —are his chairs. Sinuous and sensuous, they led one commentator to rhapsodize, “When a designer-craftsman can give the back of a simple settee a gentle curve that is sheer controlled voluptuousness, or taper a chair arm into a flattened swell as organic as the human arm that will rest upon it, he has achieved the ultimate in elegance…” Maloof’s chairs are comfortable to sit in and inviting to touch. Few examples of modern design can surpass them for visual and tactile delight.

Evaluating his career in 1983, Maloof quoted Emerson, who said “I look on the man as happy who, when there is a question of success, looks into his work for his reply.” By this measure, or by any other, Sam Maloof was a successful and a happy man. “God willing,” he wrote in the early 1970’s, “I don’t want to retire. I could work with my hands as long as I live…” Sam Maloof worked with his hands up until the month before he died. His life, and his work, are now a part of our cultural heritage, and will remain a source of inspiration to craftsmen, and to all who enjoy craftsmanship.

Eight years later, Maloof’s work retains its blue-chip status in the vintage design market. Maloof’s legacy is perpetuated by The Sam and Alfreda Maloof Foundation for Arts and Crafts, which supplied most of the images for this re-post.