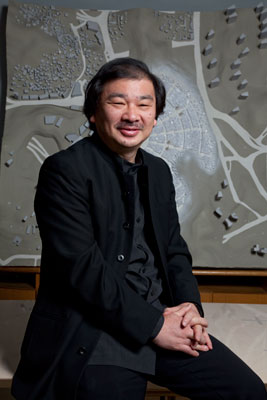

Shigeru Ban: 2010 Hall of Fame Inductee

To truly understand this Japanese designer, you have to dig into his quarter-century love affair with cardboard. Architectural innovation, as Shigeru Ban likes to note, often follows the introduction of a new material. Born in 1957, Ban began experimenting with it in his 20’s, using lengths of ordinary cardboard tubing as if they were noble planks of solid wood. Compared with timber elements, however, the paper cost little, weighed less, and was spectacularly Earth-friendly. The recycled-paper tubes chosen for his lyrical 1986 Alvar Aalto exhibition at Tokyo’s Axis Gallery—what Ban terms his first “paper architecture”—cleverly avoided, as he says, wasting “precious material for a temporary installation.”

Skeptics wondered whether a material so improbable and obviously ephemeral as cardboard could endure. The architect himself draws a favorable comparison with concrete structures, which he says seem solid until they crumble suddenly in an earthquake. In fact, Ban’s paper architecture has come to the rescue several times for disaster relief. Following the 1995 Kobe earthquake, he designed a Paper Church built by 160 volunteers in five weeks. He responded immediately when Interior Design Hall of Fame member Calvin Tsao reached out for help following the 2008 Chengdu, China earthquake. “It immediately hit me that we needed someone like Shigeru,” says Tsao of the connection, which ultimately resulted in Ban’s design for a temporary school. “He’s really a great sport.”

After Shigeru Ban Architects was hired as part of the design team for Centre Pompidou-Metz, a satellite museum of the capitol’s iconic institution in the Northeastern French city of Metz, Ban built a temporary Paris studio using cardboard. Eschewing high rents, Ban created a pavilion on a terrace of the Pompidou’s Beaubourg headquarters by Renzo Piano and Lord Richard Rogers. When the Metz opened earlier this year, the studio was disassembled, although Ban reports a plan to re-erect it as offices for the Paris museum staff.

He delivers this news with the minimum possible drama, sitting at a Poul Kjaerholm white marble table in the pristine new Metal Shutter House apartment building he designed for a New York site bordered by recent Frank Gehry and Jean Nouvel structures. The metal-shutter exterior is veiled by perforated-steel security gates that roll down at the push of a button, transforming them from purely practical into improbable poetry. “I hate to be influenced by a fashionable style,” Ban says in his softly Japanese-accented English to a small audience that leans in to catch his comments.

There is also, however, a lighter side to this serious man according to Dean Maltz, an American business partner who is in the process of incorporating a stateside outpost of Shigeru Ban Architects. Maltz has known Ban since the two were students at the Cooper Union, and he pitched in to create the 2005 Nomadic Museum on a New York pier in the Hudson River. The temporary construction had cardboard trusses topping walls made using 148 locally sourced shipping containers stacked like bricks. Identical containers were available in Los Angeles, so none were transported there a year later for a reinstallation, creating a laughable spin on the concept of free shipping. Or consider the dryly named Curtain Wall House of 1995. Instead of the expected glass and steel, a photo of the project shows a billowing, wind-whipped two-story drapery hung from edge of the project’s roof. Turns out that this designer’s Zen calm services quiet wit that loves to tell a sophisticated joke.