Two New Art Festivals Boost the American Midwest’s Culture Quotient

Midwesterners who are arts enthusiasts need no longer travel to a major metropolis for their cultural fix. This summer, Cleveland and Kansas City, Missouri, have both launched citywide exhibitions bidding for spots on the international art-tourist itinerary.

“Our goal is to create a new world-class art destination,” collector and philanthropist Fred Bidwell says. The former advertising executive jump-started “Front International: Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art,” running through September 30. The ambitious project pulls together a global roster of over 110 artists; eight presenting partner institutions, including museums in nearby Akron and Oberlin; and 28 venues as diverse as the Cleveland Clinic. With $5 million dollars in private and public funding, Front has support from community leaders, politicians, local businesses, and volunteers—thousands of whom attended the opening celebration.

Notwithstanding Front’s international ambitions, what most distinguishes the festival is its sense of place. The triennial’s theme may be “An American City,” but that city is unambiguously Cleveland. As artistic director Michelle Grabner explains, the city is used as “a laboratory to evaluate and interpret the contemporary urban condition.” Themes permeating the various exhibitions—racial tension, immigration, gentrification, urban overcrowding, and economic development among them—resonate with metropolises around the globe.

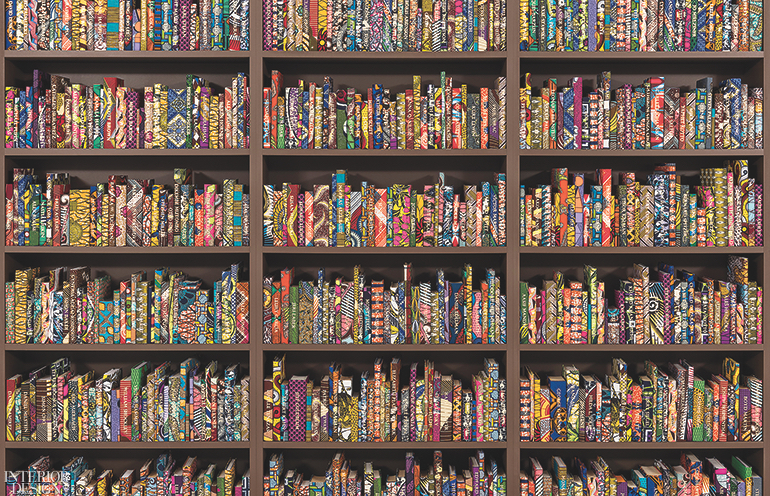

Front’s indoor and outdoor installations, about a third specially commissioned, are concentrated in three neighborhoods. Grabner, a painter as well as a curator, played matchmaker between venues and artists, resulting in works particularly relevant to their locations. Among the standouts is Yinka Shonibare’s installation of 6,000-odd books displayed on shelves in the Cleveland Public Library. Covered in his trademark African wax cloth, the books are embossed with the names of immigrants, many of them Clevelanders, who have contributed to American culture. Also memorable are Dawoud Bey’s shadowy photographs, which evoke fleeing slaves on the Underground Railroad, installed in St. John’s Episcopal Church, one of the escapees’ last stops before Canada. Philip Vanderhyden’s video scenes evoking financial fluctuations and instability appear on 24 screens inside the calm and reassuring Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. The latest iteration of Brazilian Marlon de Azambuja’s ongoing sculptural exploration of Brutalist architecture is an assemblage of locally gathered construction materials at the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Notable outdoor commissions include Tony Tasset’s 25-foot-tall sculpture of a silver hand resting spiderlike on its fingertips on the Case Western Reserve University campus. A few miles away outside a converted transformer station, a sculpture by A.K. Burns uses mangled black chain-link fencing to comment on the location’s gentrifying neighborhood. Canvas City, an ongoing mural project downtown including works by such artists as Sarah Morris and Odili Donald Odita, has been inaugurated with the re-creation of a 12-story mural done in 1973 by Julian Stanczak, a Polish painter who lived in Seven Hills, Ohio, until his death last year.

“Open Spaces 2018: A Kansas City Arts Experience,” from August 25 through October 28, is a projected biennial event combining performing and visual arts. Like Cleveland, it began with the vision of one man, in this case artist turned real-estate developer Scott Francis. From the start, artistic director Dan Cameron, who founded “Prospect New Orleans” in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, saw music as an essential element in the mix: “Music-making is a point of pride in Kansas City,” he says, referring to its role in the development of modern jazz through such giants as Count Basie and Charlie Parker.

With a budget of some $3.5 million, Cameron assembled 45 exhibition artists and more than 50 performers, some of whom work in both categories. Almost half are from Kansas City. Along with music, the varied offerings include dance, theater, spoken word, and performance art along with painting, sculpture, photography, and video exhibitions, most commissioned for the exhibition. “We are presenting the city as dynamically diverse,” Cameron continues, “so it comes across as the really cool place that it is.”

Swope Park, an 1,800-acre expanse that splits Kansas City in two, is the hub of activity, with a dozen outdoor art projects, free staged performances, and food events presented every weekend. Another 10 projects are installed around the city—the Kansas City Art Institute, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, and the American Jazz Museum, the latter featuring a work by Sanford Biggers, among them—as well as in galleries and the musician’s union headquarters. Capping off the celebrations, a gala weekend of ticketed concerts in mid October will feature Kansas City native Janelle Monáe along with the Roots, Vijay Iyer, and local music groups.

Notable installations include one by Missouri-native Nick Cave, who has transformed a former Roman Catholic church into a multiscreen video environment evoking the Middle Passage, the period enslaved Africans spent chained on ships crossing the Atlantic Ocean. Meanwhile, local sculptor Dylan Mortimer has taken a dead tree in Swope Park and turned it into a site-specific installation embellished with beads and sequins.

Whether these two events will attract thousands from outside the Midwest remains to be seen at the time of our publication. What’s not in question, however, is their importance in furthering regional pride, strengthening community, encouraging local development, and demonstrating that the arts are as powerful a way as any to expand horizons and deepen perceptions.

> See more from the August 2018 issue of Interior Design