Victoria Lautman Explores India’s Vanishing Stepwells in New Book

In 1986, when I was the editor in chief of this magazine, our publisher, Lester Dundes, had an idea for a design-related excursion to India. There would be good publicity, it would make some money, and he and his wife would have a free trip. But shortly before he and the 20 designers who had signed up were to leave, his wife fell ill, and he told me and my partner, Paul Vieyra, that we would have to go instead.

I was elated at the prospect of seeing India. It is not easy, however, to arrange leaving a monthly magazine for three weeks, especially on short notice. My staff, including Edie Cohen, now deputy editor, pitched in and made it work.

As planned, our group was met at all our destinations by skilled guides, so I needed no knowledge of India, just responses to participants’ comments such as “I don’t like my room” or “I can’t eat this food” or “I’ve lost my passport.” Members of the Chicago contingent were particularly jolly and impressive, among them the future Hall of Fame members Donald D. Powell and Robert Kleinschmidt of Powell/Kleinschmidt and the ebullient young journalist Victoria Lautman, who had her own art-centric radio program in addition to appearing on TV. Her latest book, The Vanishing Stepwells of India, grew out of her discoveries on that trip and many others afterward.

In several cities, our itinerary featured visits to the studios of designers and sometimes, in the evening, to their homes. We spent a morning in Bombay, as it was known, with the chief designer of the Taj Hotels Resorts and Palaces chain. In New Delhi, we saw the giant government complex designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens and took a rare tour of the former British viceroy’s residence.

Chandigarh’s master plan and government buildings by Le Corbusier were a highlight, of course. Before we got to see them, however, Lautman asked our bus driver to stop at something called the Rock Garden, a vast labyrinth that the artist Nek Chand had surfaced with colorful broken tiles. I would read later that this was second only to the Taj Mahal in the number of daily visitors. At the time, the rest of us were eager for Corbu and impatient with anything else. We left the Rock Garden more quickly than she would have liked.

In Jodhpur, we stayed at the Indo-deco Umaid Bhawan Palace, with its vast domed entry ringed by dozens of uniformed staff. In Udaipur, at the Taj Lake Palace hotel, covering all of a tiny island, she was assigned a room at the top that had a private terrace with an amazing view of the city. So she arranged a cocktail party for our whole group.

On to the textiles center of Ahmedabad, where there were more Corbu buildings. We were invited to dinner at one of his most famous houses, the Villa Sarabhai— something arranged for us by future Hall of Fame member Jack Lenor Larsen, who knew the owner. The vegetarian food was eaten with our fingers, but it was one of the most elegant and delicious meals ever, anywhere.

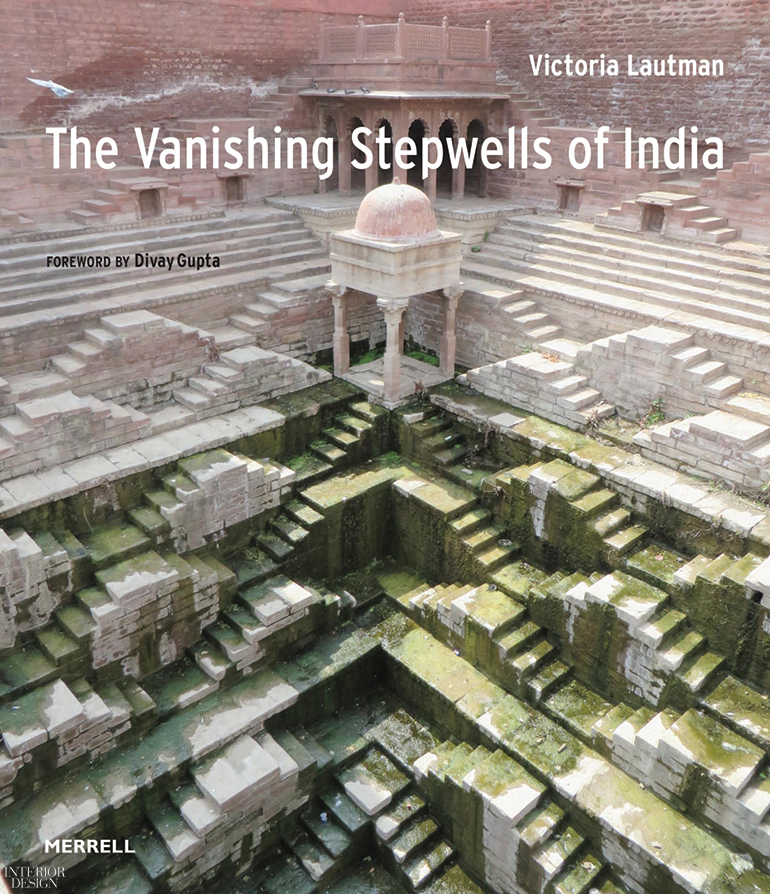

It was also outside of Ahmedabad that we saw our first stepwell, either vav or baoli in Gujarati or Hindi, respectively. A kind of below-grade structure unique to India, a stepwell descends to the water table, and some incorporate cisterns, channels, and bathing spots. Despite serving these very utilitarian functions, dating back to the fourth century A.D., over time stepwells became more and more richly ornamented, like upside-down temples. Sculptures might include crocodiles, sea creatures, and gods.

Often built along ancient trade routes, spaced to match the distance of a day’s march, stepwells are abundant in Ahmedabad and the surrounding state, Gujarat. The one we saw in the city, the Amritvarshini Vav, and a larger and more famous one, the Rudabai Vav in a village just to the north, both appear in Lautman’s astonishing and valuable book, out this past spring from Merrell Publishers. Here, from the preface, is her perfect description of a descent into one of these wonderful treasures, now endangered: “Sweltering heat turned to an enveloping cool, and the din above ground became hushed. The glaring sunlight dimmed with each step, but where those steps led was not discernible. Views telescoped into indefinite space, constantly shifting, and I could tell neither the depth nor the length of the structure. Towers of ornately sculpted columns loomed over me, sunlight filtered in, a pool of water appeared, and it all seemed like an enchanted alternative reality. And that is exactly how a stepwell would have been experienced a thousand years ago.”

I think many of us were awed by these strange structures. But none more than she.

> See more from the October 2017 issue of Interior Design