10 Questions With… Jordan Rogove of DXA Studio

Jordan Rogove and Wayne Norbeck, principals and co-founders of New York-based architecture firm DXA Studio, believe in the life-changing potential of design competitions. So much so that they make a point of entering at least one a year, and they even credit the 2011 launch of their firm with the early wins and resulting press that grew out of evenings spent ideating together when they both worked elsewhere (Rogove at Morris Adjmi Architects and Norbeck at what is now Gluckman Tang Architects). The two first met as students at the Virginia Tech School of Architecture, and today they’re pushing sustainable building forward with projects like FutureHAUS, a groundbreaking prefabricated smart home, and have become experts at navigating complex municipal approval processes all in the name of good design. Here, Rogove (pictured above at right) tells us why he thinks of the High Line as this generation’s Central Park, and why architects need to educate the world about their own value.

Jordan Rogove and Wayne Norbeck, principals and co-founders of New York-based architecture firm DXA Studio, believe in the life-changing potential of design competitions. So much so that they make a point of entering at least one a year, and they even credit the 2011 launch of their firm with the early wins and resulting press that grew out of evenings spent ideating together when they both worked elsewhere (Rogove at Morris Adjmi Architects and Norbeck at what is now Gluckman Tang Architects). The two first met as students at the Virginia Tech School of Architecture, and today they’re pushing sustainable building forward with projects like FutureHAUS, a groundbreaking prefabricated smart home, and have become experts at navigating complex municipal approval processes all in the name of good design. Here, Rogove (pictured above at right) tells us why he thinks of the High Line as this generation’s Central Park, and why architects need to educate the world about their own value.

Interior Design: DXA Studio, established in 2011, is relatively young. What’s the firm’s origin story?

Jordan Rogove: Wayne Norbeck, my partner and cofounder of DXA studio, and I met as architecture students at Virginia Tech. After a chance encounter in Union Square in the late aughts, we took to moonlighting and entering competitions. When we started winning them and getting press, it coincided with our clients encouraging us to leave our respective studios and launch our own, so the decision to do so was made for us! We started with some great projects, including health-focused housing in Haiti, a residential conversion in TriBeCa, and a collaboration with Steven Harris, all from a stalled project site in the West Village. We had a storefront and the likes of Julianne Moore, Lou Reed, and Irina Shayk as neighbors, walking by and waiving daily. It was surreal. Perhaps the only neighborhood in the city where you can have walk-in clients!

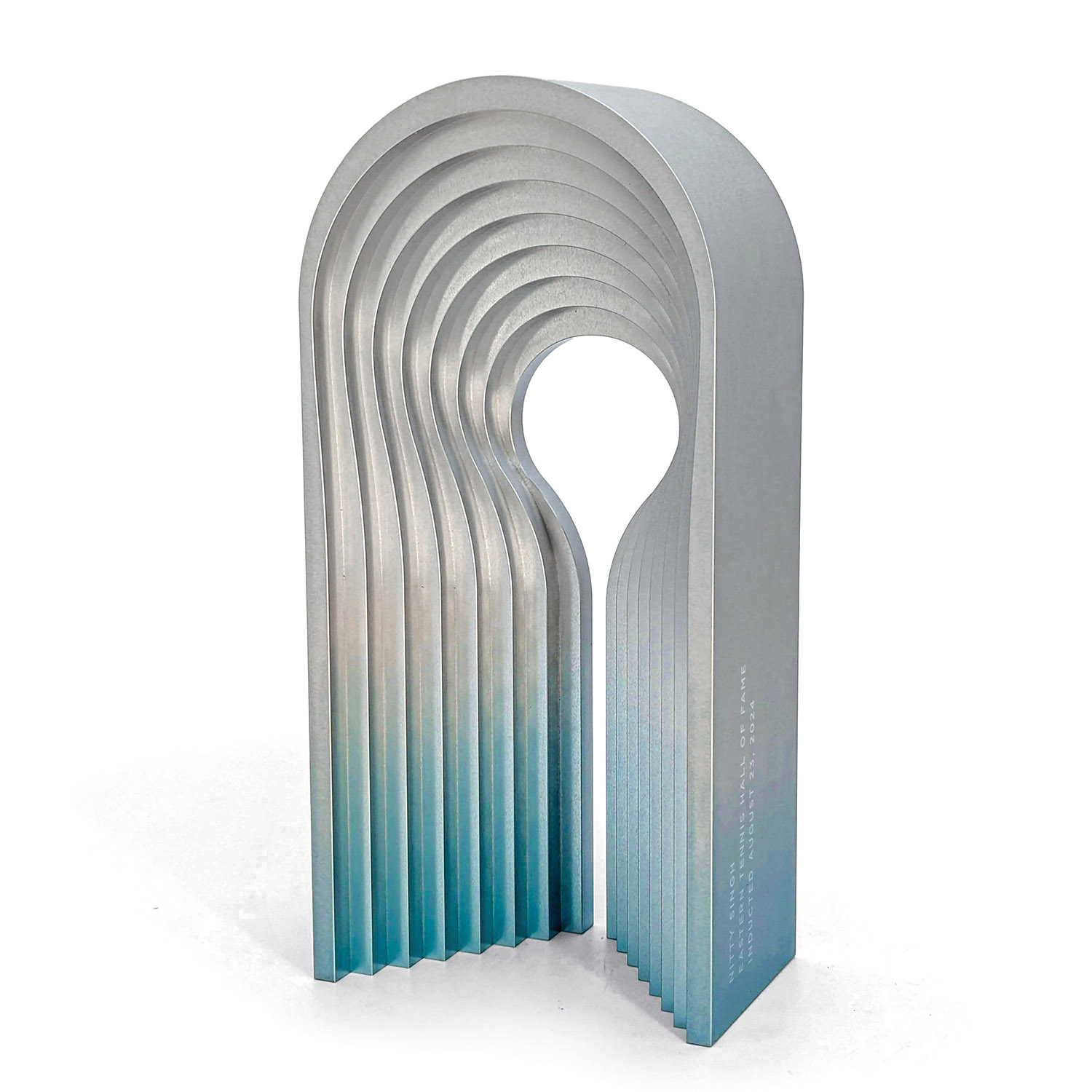

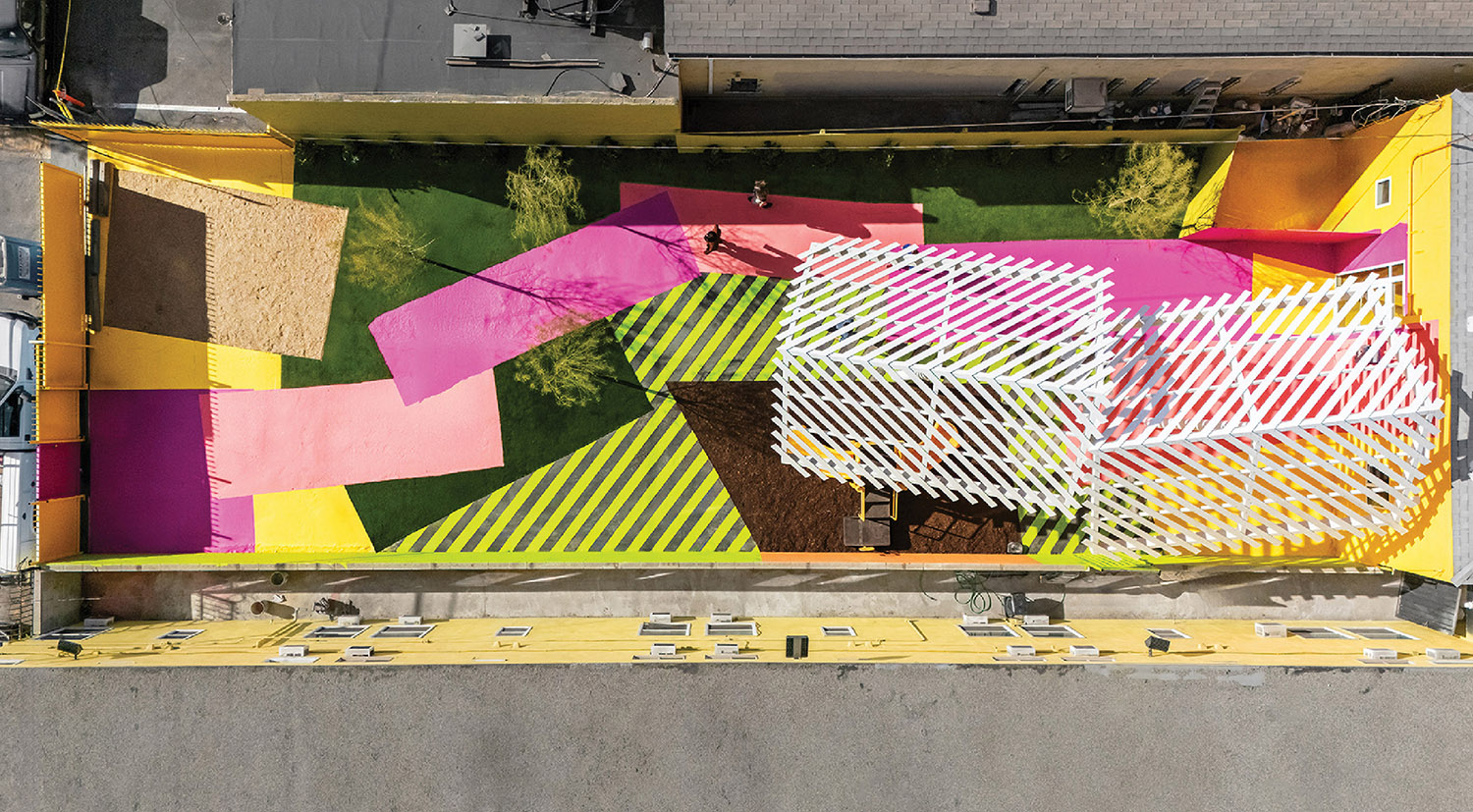

ID: Your firm’s Midtown Viaduct concept, a floating pathway, won the 2019 Metals in Construction Design Challenge. What sparked that proposal?

JR: Since part of what opened the doors at DXA was competitions, we enter at least one a year, selecting one that represents either a tremendous opportunity to design or learn on a topic we know little about. The Midtown Viaduct project was the former, which was a chance for us to imagine what a park like the High Line could be if it was initially intended to be a park, and if it was built today, using contemporary technologies. We were also cognizant of the tremendous history of the site, and the late Penn Station. We tried to weave today’s construction methods and technological advances with a form and structure that might recall the beauty of the lost station yet remain decidedly of today. We also wanted to fuse together a number of poles that currently don’t seem to connect very well, the new Moynihan, the High Line, and Hudson Yards, the latter of which seems oddly inaccessible from the other two.

ID: What’s your take on the High Line?

JR: The High Line brought me back to New York City in 2004. I joined Morris Adjmi’s office to manage the High Line Building project at 14th street. It is one of two buildings that the High Line passes through, and the only one that’s structure is entirely integrated. It was originally built so robustly that we were able to add a 10-story glass and steel tower atop it with no additional foundation work. We initially started the project as the first phase of the High Line began so I joined for many of the early meetings with Diller & Scofidio, Field Operations, and Friends of the High Line and had a front row seat to its development. What they created is our generation’s Central Park. What it has done to activate the Meatpacking District up to Hudson Yards is amazing. It was a thrill to be a tiny part of something so transformative and important to this city.

ID: What materials do you see transforming sustainable design and construction in the coming years?

JR: Wayne and I teach at Virginia Tech with Professor Joe Wheeler, who recently led a number of our students to a second Solar Decathlon victory with a prototype of modular housing called the FutureHAUS. We hope to bring some of the thoughtful sustainable technologies explored in this initiative to market in the coming years, as the integration of technology, superior craftsmanship, and superior performance of a modular, prefab construction are undeniable and could change the way we build for the better. In addition, we are keeping an eye on 3D printing, photovoltaic materials, and wood technologies. We are finishing a CLT (cross laminated timber) project in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, currently and hope to be able to do more of those in the coming years.

ID: How do you define the role of the architect in today’s society?

JR: Being an Architect means different things in different places. I had the good fortune of living in Paris for a bit and found that architects were held in high esteem, at least in my encounters. That the profession was felt to be a culmination of all arts, perhaps the highest of art forms. I try to remember that when sitting in a trailer and getting yelled at by contractors. Back home in the U.S. it feels as though architects are thought to be necessary for only urban development, corroborated by an estimated 98 percent of all buildings here being built without one! You definitely feel this phenomenon stepping out of the city and experiencing the sprawl, places designed to the automobile with little regard for human scale, efficiency, and interaction. I think this phenomenon puts all architects in the position of becoming advocates for the profession and its necessity. We need to educate everyone—private clients, developers, municipalities, and the like—that good design brings value, dignity, enhances health and well-being, and can foster a sense of belonging—unlike that 98 percent they are all settling for.

ID: What do you think the future holds for the design of private residential spaces in NYC?

JR: Living in New York City is a thrill. We get energy from its energy and the daily encounters with people and active spaces. When we all return home from these invigorating and often frenetic days, we want to do so in a place that is a respite from all of that activity. I believe that health and happiness are at the center of what we should be thinking about as designers here. Some of this can be addressed with good design: maximizing light and view exposures, and using thoughtful materials that feel good to the touch and are good for the environment. Some of it can also be the technologies I mentioned previously, unseen and integrated, vigilantly keeping tabs on your health and any unforeseen issues, like slip fall detection and biometric readings that indicate swings in weight or habits. I’d love for all that we design moving forward to allow our clients to age in place and not have to ship off to one of those assisted living places.

ID: What’s the most challenging project you’ve worked on recently, and why?

JR: Without a doubt the most difficult project I have ever worked on was the renovation of the Willem de Kooning studio building near Union Square. Initially our client intended to tear the building down and put up a tower, but the building was designated an Individual Landmark due to its cultural importance. We proposed fully restoring the building and instead of the tower, a multi-story addition that would be setback but visible. Given that no one has known the history of this building since de Kooning left for East Hampton in the 1960s, we thought the visibility of the addition gave us an opportunity to design a facade that paid homage to the Abstract Expressionists, with a composition that tried to evoke their focus on painting emotions and kinetic energy. The design was polarizing. To both develop it and get it approved we spent time with art historians, museum curators, artists, architects, scholars, and the community. Those that got it, chiefly the historians, scholars, architects and some members of the community, loved it. Those that didn’t, hated it. Ultimately it split right down the middle at the Landmarks Preservation Commission, and with some design changes it was eventually approved, but the journey was perilous.

ID: What do you think is the design industry’s biggest blind spot when it comes to designing sustainably?

JR: I think the biggest blind spot in our efforts to design sustainably is the same fundamental issue with trying to combat climate change. That the existential threat is not immediately recognizable. That it remains abstract allows decisions in early project meetings, especially for development projects, to focus on upfront costs on construction rather than long-term performance and savings. Collectively designers need to be able to speak knowledgeably and compel our clients with the best of our abilities to use passive standards or LEED and help bring down that staggering number of over 60 percent of all carbon emissions coming from buildings. We also need help from the local, state, and federal governments to incentivize these decisions, not penalize and chase people out of the market.

ID: Accessibility is a big part of the design conversation right now. How does your practice approach it?

JR: One of our first projects was for dear friends that have a daughter with SMA (Spinal Muscular Atrophy). They challenged us to get smart on accessibility and we set about establishing a network of experts in the field and finding materials and equipment that are well designed that could be integrated to assist her. Thinking of experiencing the home we were designing for their daughter from her vantage point, and how it would need to function for her life with and after her parents brought these challenges into perspective. We have watched in awe in the years since as they have pushed for change and greater consideration of accessibility with the Department of Education and the MTA.

ID: What’s keeping you inspired these days?

JR: We are currently working on a project in Washington, DC that is a collection of seven buildings with several public spaces and streets between them. We are meeting weekly with the other architects and designers to discuss how these buildings will work together to effectively create an entirely new and vibrant neighborhood. It is in stark contrast to the usual practice of doing a single building and responding to the world around it with limited means, and it is invigorating. We have been traveling to see other examples and doing a tremendous amount of research to make sure we get it right. Anytime I am learning, I’m happy.

Read more: 10 Questions With… Architect Francis Kéré