+Arquitectos and Gubbins Polidura Arquitectos Create Weekend Retreat in Chile

For the last 30 years, Chile’s central coast has been a locus of invention for one of South America’s most vibrant architectural scenes, its rocky cliffs studded with sober Modernist boxes or hulking Brutalist masses of unpolished concrete: structures that confront Chile’s seismic instability with a monolithic intensity all their own. Those houses, most built in the decades since the fall of Chile’s ruthless, 20-year military dictatorship in 1992, are as stoic, sturdy, and discreet as Chileans themselves—steady objects in an unsteady landscape.

But when Alex Brahm, founding partner of +Arquitectos, and Antonio Polidura, founding partner of Gubbins Polidura Arquitectos, received a joint commission for a weekend retreat near the seaside community of Zapallar, they decided not to build a Chilean house at all. Instead, the architects looked to the sinuous curves and ethereal lightness in the work of Brazilian master Oscar Niemeyer. “Compared to Brazilians, we Chileans are more introverted, more austere,” Brahm reasons. “This house is happier, more exuberant, than what you would normally build in Chile. It has more of a sense of humor, less gravity.”

Brahm’s firm, which focuses principally on commercial structures, had recently completed a large corporate office for the client’s company in Santiago. Though Brahm and Polidura had met some years before—on a trip to Brazil, as it happens—the idea they should collaborate came from the client, who had developed projects with each of the architects separately and thought that Polidura’s deep experience in designing single-family homes would prove an asset on this assignment.

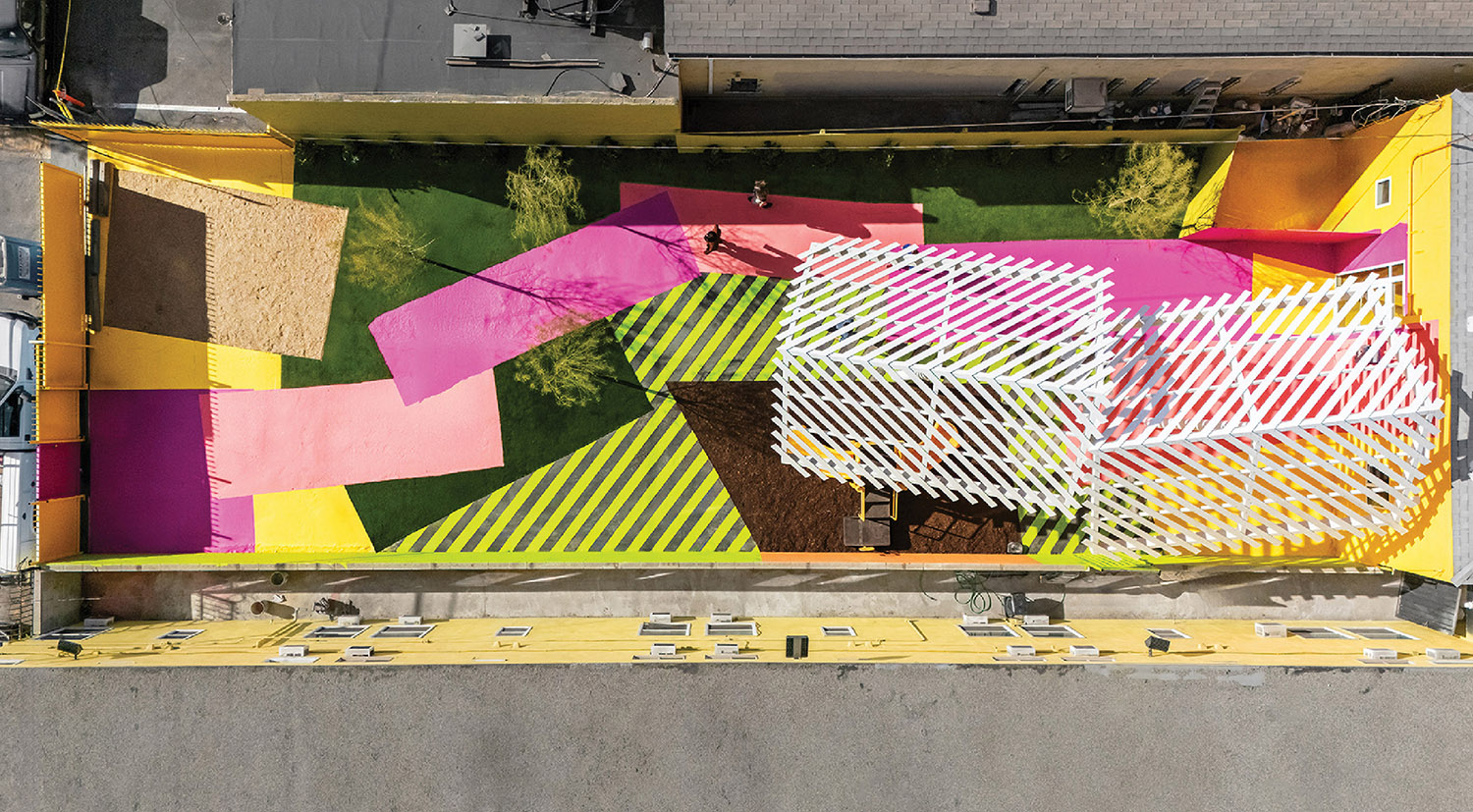

Built on a rocky perch that drops precipitously into the frigid, roiling Pacific, the house first appears as a low, clover-shape pavilion, its curved glass walls hanging from a concrete-slab roof paved with a pale gravel of crushed seashells. Irregularly shaped pavers of charcoal-gray basalt, quarried in the nearby village of La Ligua and laid piece-by-piece by a local stonemason, extend from garden pathways through the glass walls and into the pavilion’s interior, all but erasing the division between indoors and out.

Housing all the public spaces—living, dining, and kitchen areas, each occupying one of the clover’s leaves—the pavilion is, as Brahm puts it, “a habitable shadow that weighs very, very little on the landscape.” Below the pavilion, and invisible except from the sea itself, the 4,520-square-foot house’s private zones—four bedrooms, five bathrooms, and a playroom for the family’s three children—occupy a concrete bunker partly sunk into the cliff.

It’s not a typical approach to the problem of Chile’s constant, occasionally devastating, earthquakes, but like most Chilean houses, its form is nonetheless defined by the special challenges presented by the country’s exceptional seismicity. “The pedestal below is typically Chilean, with lots of strong walls to withstand the earthquakes,” Polidura says. “But upstairs we wanted to make something really light and transparent, without diagonal beams, and to do that we had to make the structure as low to the ground as possible.” Hence the open-plan pavilion’s roof floats on 21 steel columns a mere 7 1/2 feet tall. To create more headroom, the architects sunk circular living, dining, and kitchen areas up to 2 feet into the floor, outfitting each pit with custom built-in furniture. The only objects taking up vertical space are a set of Isamu Noguchi hanging paper lanterns and a suspended steel fireplace.

“The low ceilings have an interesting effect,” Brahm reports. “When you’re inside the house, the delicate slab sits right over your head, directing your focus completely to the horizon. And from outside, the whole structure seems transparent because you can’t even see the furniture—not a single object blocks your view.”

Under an oculus at the center of the light-filled pavilion, a graceful spiral stair leads down to the enclosed private spaces below. Compared to the public floor, whose modish curves and sunken pits are a cheerful, witty throwback to 1960s futurism, the lower level is almost monastic: the Brazilian exuberance above rests on a foundation of Chilean functionalism. “We wanted the downstairs to feel more like a cave than a conventional house,” Brahm says, “as if it was part of the rock itself.”

That doesn’t mean dark or oppressive, however. In the master bathroom—essentially a long, squared-off tube oriented toward the ocean—a wall of glass doors fronting a shower and sauna is reflected in a 20-foot-long mirror over twin sinks, expanding the view through the single square window into something like infinity. A square bathtub embedded in the floor beneath the window echoes the sunken-room strategy upstairs: the careful lowering of architectual elements out of the line of sight. Whereas the pavilion’s sinuous glass curtain brings the outside in, the rectangular windows in the downstairs rooms frame the views, transforming them into artworks, “almost like paintings of the sea,” as Brahm puts it.

For all its intelligence and creativity, the house is also “a sort of caprice,” Brahm readily admits. “The form is sensual and sinuous, but it doesn’t have a particularly deep architectural foundation.” Yet that sensuality has its own kind of logic. Rather than taking the route of Chile’s concrete-and-glass boxes, which seem to assume the simplest solution must be the best one, Brahm and Polidura have answered the problems posed by the rugged Chilean Pacific differently: “If it’s possible,” they say, “why not do it?”

Project Team: Hernán Fournies: Architectural Consultant. Juan Grimm: Landscaping Consultant. Greene During Iluminacion + Luxia Lighting: Lighting Consultant. Bming Ingenieros: Structural Engineer. Daniel Alemparte: General Contractor.

Project Sources: Vitra: Pendant Fixtures, Floor Lamp (Dining Room). Interdesign through Santa & Cole: Floor Lamps (Living Room, Master Bathroom). Kohler Co.: Tub, Tub Fittings, Sink, Sink Fittings (Master Bathroom), Faucet (Kitchen). Throughout: ProImagen: Custom built-in Furnishings and Staircase. Silent Gliss through A-Cero: Curtain Rails. Anodite through Schüco: Windows, Doors. Budnik: Flooring.

Read next: 12 Living Spaces that Bring the Outdoors In