At Google’s London Office, AHMM Overturns Decades of Workplace Norms

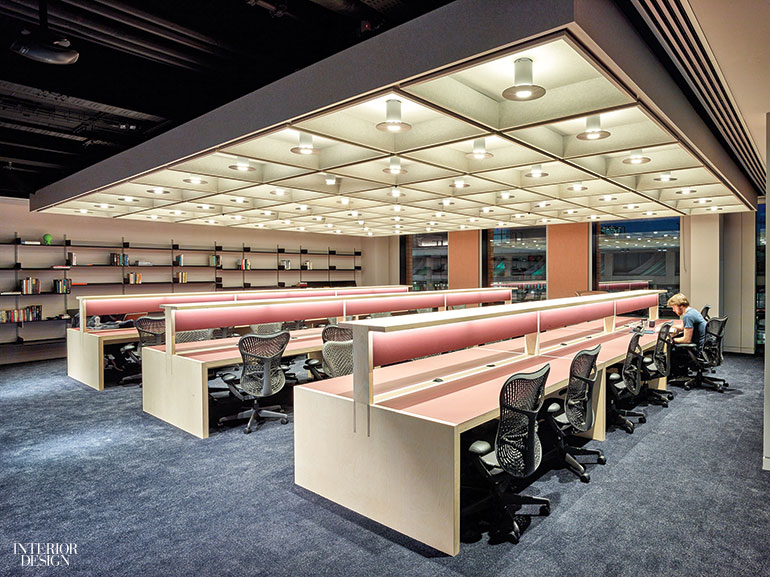

With spiraling slides, Ping-Pong, and lots of primary colors, Google pioneered the playground-office aesthetic of the early nineties. Now the company is just as enthusiastically embracing the opposite, a restrained design that is flexible and sustainable. This approach just made its debut in London. Granted, the office still has a Ping-Pong table, but it’s in a curtained-off part of the gym. As for the slides and the primary colors, they are truly a thing of the past. “People just need to be able to work, and those spaces often proved difficult to work in,” Allford Hall Monaghan Morris associate director Ceri Davies says. “It doesn’t matter how much money you throw at something to make it quirky. If it’s not comfortable from an acoustics or ergonomics point of view, the perks become a distraction.”

The AHMM-designed current premises—a stone’s throw from where Google plans to open its first purpose-built headquarters outside the U.S. and eventually create a campus—are in the buzzing King’s Cross area, also home to the St Pancras International station with Eurostar service to Paris. More specifically, Google occupies a 12-story building that Wilmotte & Associes designed for a French bank that never moved in. The bank intended to rent out the lower stories as well as the penthouse. In the end, Google took over the entire building—which was a boon, Davies says, given that the penthouse has a higher ceiling and a spectacular terrace. She then embarked on designing 375,000 square feet to house 2,500-plus Googlers, as they’re universally known, including some who work for subsidiary YouTube.

While the bank’s proposals for its own reception area, in what would have been a shared atrium lobby, had been predictably conservative, Google reception eschews formality—no monolithic marble desk here. The dusky pastels of overdyed vintage rugs and Doshi Levien’s angular chairs and love seats add to the hotel-like atmosphere. Viewed from upper levels or the glass elevator, reception is a landscape of color, geometry, and movement. Connecting the topmost levels, sculptural blackened-steel staircases and bridges make the atrium more dynamic. “A lot of atriums end up being dull goldfish bowls, where not a lot happens. It was important for us to get some physical movement up and down,” Davies explains.

On the practical side, reception’s furnishings can be easily moved around or taken out should the space be needed for a big event. “It’s about being able to curate rather than being wedded to a fit-out until you can afford to change it,” she says. Google’s embrace of the new design direction was driven not only by the desire to move away from heavily themed interiors but also by concerns about the waste and cost associated with continually updating spaces “whenever a business group wants a different scenario,” she notes.

Central to the flexibility concept is a modular meeting and videoconferencing room, which is easy to construct, deconstruct, and reconfigure in multiple ways. The Googlers gave it the name Jack, and it’s built with plywood panels that can be simply bolted together. When assembled, the plywood interiors are tactile and fragrant, the opposite of office-standard white-painted plasterboard. She left both the interiors and the exteriors purposely neutral for personalization with different cladding and shelving. AHMM even prepared a helpful manual encouraging everyone to Hack a Jack.

Several factors differentiate Jack from similar pods on the market, she says, adding that the materials needed to make the panels can be found anywhere: “You just need the template and a CNC router.” Other major points of difference are the state-of-the-art acoustical performance and fire resistance achieved by getting just the right ratio of solid cementitious board to insulation and air and perforating the panels to stop reverberation. To deal with the biggest challenge posed to movable meeting rooms—connecting to ventilation—she put extra fan-coil units in the building’s ceilings, on a grid. A Jack can be placed anywhere within 16 feet of a fan-coil unit. Move the Jack away later, and the unit can be capped until it’s needed again.

For all AHMM’s successes overall, among them winning the Royal Institute of British Architects’s top honor, the Stirling Prize, the firm is not known for interiors. Its first major completed interiors project, in fact, is Google. And although, it must be noted, the London headquarters commission ultimately went elsewhere, AHMM’s influence on the Google culture is already widely felt, thanks to Jack. The London office has put up a staggering 165 units, and versions have appeared at offices in Berlin and India in addition to global headquarters in Mountain View, California.

Project Team: Simon Alford; Rachel Bate; Santiago Fernandez; Pilwon Kim; Petr Kolacek; Edwina McKnight; Jasper Middleton; Goh Ong; Briony Paul; Ana Perez-Bustamante; Chris Reddaway; Marian Ripoll; Steve Smith; Peter Smith; Jamie Strang: Allford Hall Monaghan Morris. Mott MacDonald: Materials Consultant. Sturgis Carbon Profiling: Sustainability Consultant. Cundall: Lighting Consultant, MEP. Waterman Group: Structural Engineer. Sandy Brown Associates: Acoustical Engineer. Brown & Carroll: Woodwork. Integra Contracts: Ceiling Contractor. Arminhall Engineering; John Desmond: Stair Contractors. ISG: General Contractor.