Core Curriculum: NYU’s Steinhardt School by LTL Architects

Integrating disparate fields of study, everything from engineering and health care to studio art, is the aim of New York University’s teacher’s college, the Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development. The result is a holistic pedagogy that NYU calls “education for social change.” When Steinhardt’s physical environment needed its own change, NYU turned to LTL Architects, notable for previous work at Columbia and Gallaudet Universities. LTL principal Marc Tsurumaki was willing to take on the additional challenge of splitting the NYU project into two phases, so the school could stay open.

“Steinhardt’s premier departments had been scattered through different buildings,” Tsurumaki says. “We broke down this silo tendency, common in academia, by consolidating the departments.” Each now lives on contiguous levels in Steinhardt’s main building. Dating from the early 1900’s, it offers roughly square floor plates, with LTL’s gut renovation encompassing 70,000 square feet on seven levels—seven opportunities to embed the mission of the school in its very bones.

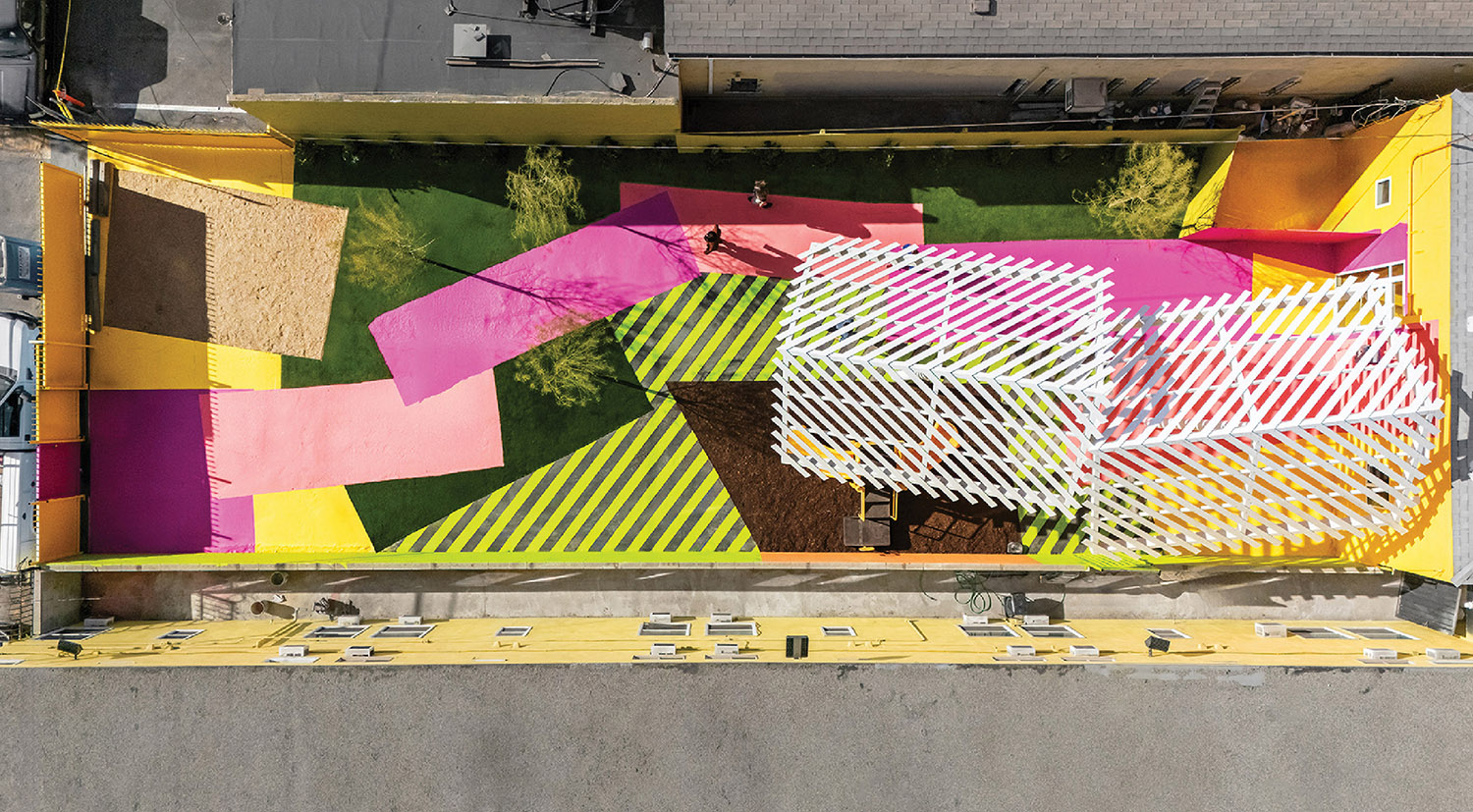

Right at the elevators, departmental identities are established by small lettering in stainless steel paired with supergraphics in block capitals. Departments also have certain accent woods, used everywhere from flooring to built-in seating and shelving. Conversely, several levels’ feature walls combine multiple shades of green: emerald, forest, and apple-for-the-teacher.

“The Department of Teaching and Learning devotes one of its cores to reading skills.”

Central areas, ringed by circulation paths, are “programmatic cores,” Tsurumaki says. “And each core has its own character.” The Department of Teaching and Learn-ing, for example, devotes one of its cores to reading skills. First comes a library that enchants young visitors with child-size furnishings. Extensive maple shelving holds children’s books here, then extends into a larger reading room, where the books are joined by interactive teaching aids. As he explains, “One line of wood slopes up from a child’s height to become an adult-height wall.” That’s a clever representation of the library’s role, not only teaching children but also teaching adults how children learn.

Even more innovative, another of the department’s cores is devoted to science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and the environment: The S. Jhumki Basu STEME Education and Research Center’s teaching studio contains not only the requisite videoconferencing technology and remote-learning “smart” whiteboards but also an installation that truly embodies the role of a teacher. A stainless-steel display system, with shelves spanning child and adult heights, also incorporates giant Fresnel lenses that can slide back and forth on rails, magnifying whatever sits behind—parapher-nalia for examination ranges from human skulls and turtle shells to atom models. It’s shelving as microscope, at once form and function.

Cores always serve at least two functions. With the STEME Education and Research Center, the studio and a resource room share the core. A level below, the core is broken out into a student commons and a lounge in front, a run of offices in back, and a wedge of storage down the middle. The commons and the lounge are acoustically isolated from each other by glass doors. Open those doors, though, and the two become “a major space, a large meeting room,” Tsurumaki says. “Flexibility, thinking of shared territories, can foster different levels of collaboration within and between departments.”

“It’s shelving as microscope, at once form and function.”

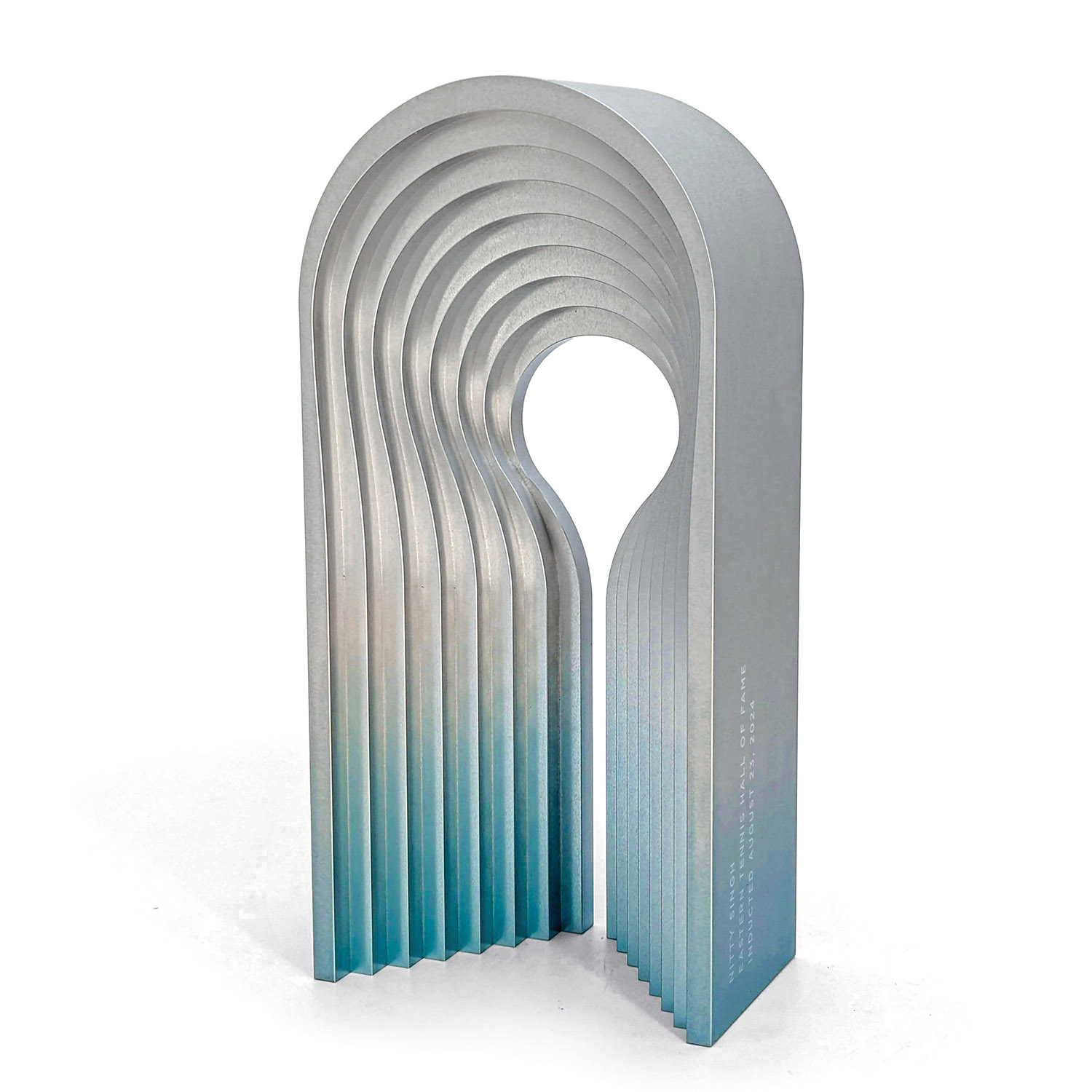

Sculptural canopies floating above the various cores, underneath the original ceiling, call them out as “central plazas, hierarchically more important than the perimeter offices,” he continues. Those private domains are crucial, however, in academic environments, he explains: “It’s one of those cultures where the idea of closed offices still has a lot of traction. Faculty are holding office hours, which require privacy, and are also doing research and need study time for themselves.”

A ring of offices can, of course, hugely reduce the amount of natural light in a building’s interior. To address this, he turned to standard approaches, notably clerestories, to admit daylight into the hallways around the cores. However, there was actually too much light in one area, the student commons at the top of the building, where existing skylights produced glare, heat. . .and complaints. So he had the bright idea to place a reinterpretation of the cores’ canopies beneath the skylights, both buffering and diffusing the power of the sun.

Speaking of power, mechanicals also needed a rethink. “It was a hodgepodge of systems cobbled together over 20 years,” Tsurumaki says. He had to start from scratch in order to tie the building to NYU’s cogeneration plan, which provides heating and cooling for most of the campus buildings. Instead of wasting precious square footage on multiple mechanical rooms, he centralized everything on the roof; removing dropped ceilings and remodeling air ducts then allowed him to maximize the ceiling height. The mechanicals work was an important factor in the new Steinhardt being designated LEED Gold, A-plus proof that ethics and aesthetics can go hand in hand.

Project Team: Paul Lewis; David J. Lewis; W. Clark Manning; Jason Dannenbring; Kristen Alexander; Keith Greenwald; Kevin Hayes: Ltl Architects. De-Sign 360: Graphics Consultant. Tillotson DeSign Associates: Lighting Consultant. Sextant Group: Audiovisual Consultant. Steven Winter Associates: Leed Consultant. Robert Silman Associates Structural Engineers: Structural Engineer. Thomas Polise Consulting Engineer: Mep. Structuretone: Construction Manager.