Ken Wampler: 2013 Hall of Fame Inductee

As a college student, Kenneth Wampler admits, he enrolled in a clown course. The instructor went on to fame as Star Trek: The Next Generation’s Dr. Beverly Crusher, and Wampler explored acting, too. He recounts the horror of one particular audition for a big-time producer: standing in a church basement, holding up his own 8-by-10-inch head shot in a lineup. The scene could have come straight out of A Chorus Line.

Wampler was apparently not destined for show biz, but he had always dreamed of a life in the arts. As a child, he sketched nonstop and learned to paint with watercolors. In young adulthood, he was intrigued by the storied Omega Workshops, the free-spirited London enterprise that included Virginia Woolf’s sister, Vanessa Bell. Omega fearlessly painted on everything from plates to window frames. “No surface was safe around them,” Wampler says with a laugh.

Following a year in London, he put down roots in New York and worked on theatrical costumes and women’s wear. To paint silk yardage for the idiosyncratic designer Mary McFadden, he rented a funky live-work loft. “There were roommates all over the place, but I needed the space,” he recalls. He experimented with florals, with dyeing, and became expert in the wax-resist technique. “I really loved painting fabric, but I didn’t get along with fashion one bit,” he says. Finding it “too mean,” he switched to 18-inch shantung squares for throw pillows. His customers were Parish-Hadley, Renny B. Saltzman Interiors, and?Samuel Botero Associates. He suspended operations, however, when friends began contracting HIV/AIDS. “It was hard for me to paint pillows for the super-wealthy,” he explains, “when a lot of people I knew were scared, sick, and dying.”

His volunteer work for the HIV/AIDS charity known today as Bailey House turned into a full-time job, and he went back for a master’s degree in social work. “Those days were just so awful,” he says with a shudder. “The virus struck a whole swath of young people who were not on a solid career path, and then the bottom fell out for them.” Before the existence of today’s drug cocktails, health for the infected remained touch-and-go. Bartending and other fast-paced jobs were not conducive to maintaining stability after diagnosis. Wampler thought the decorative arts might be.

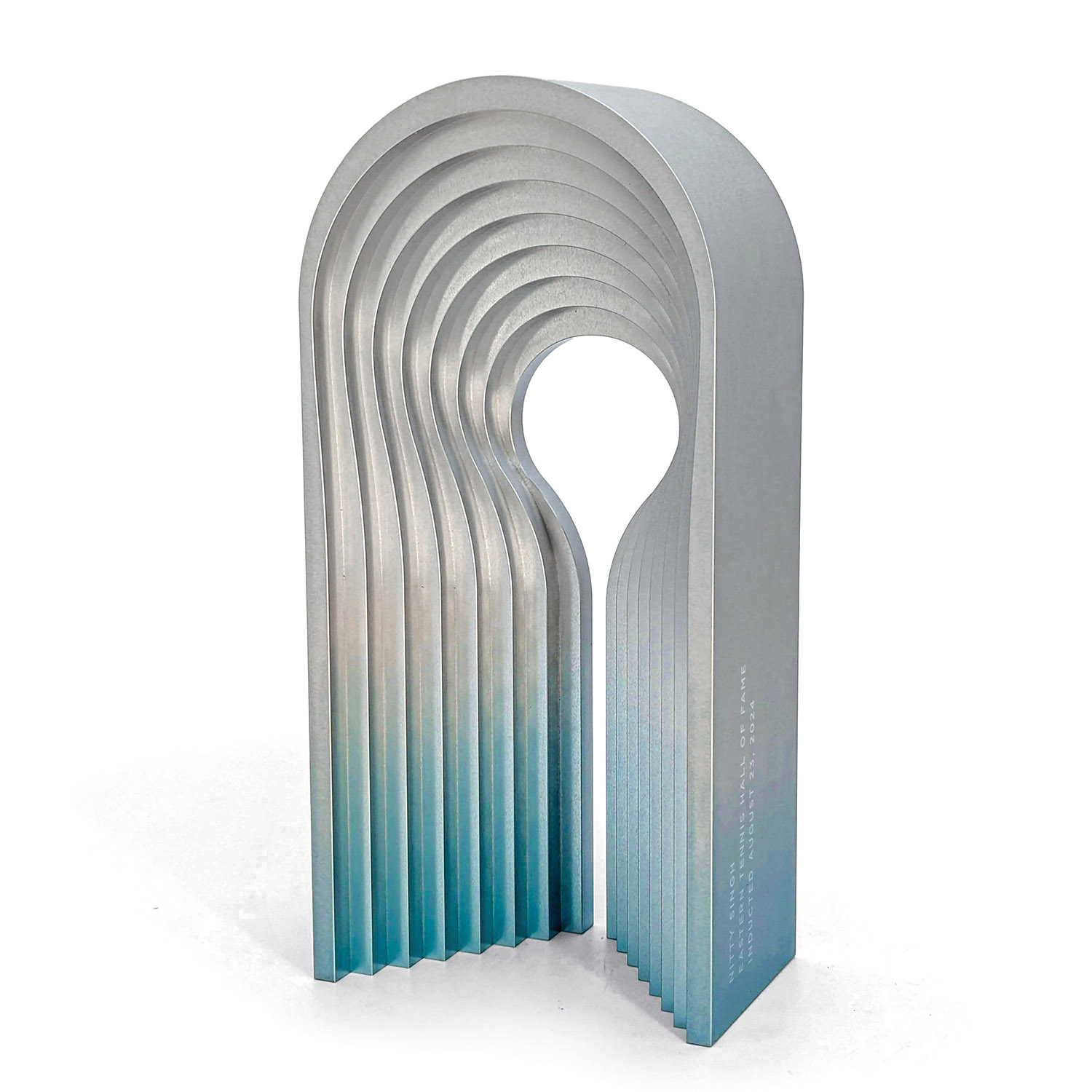

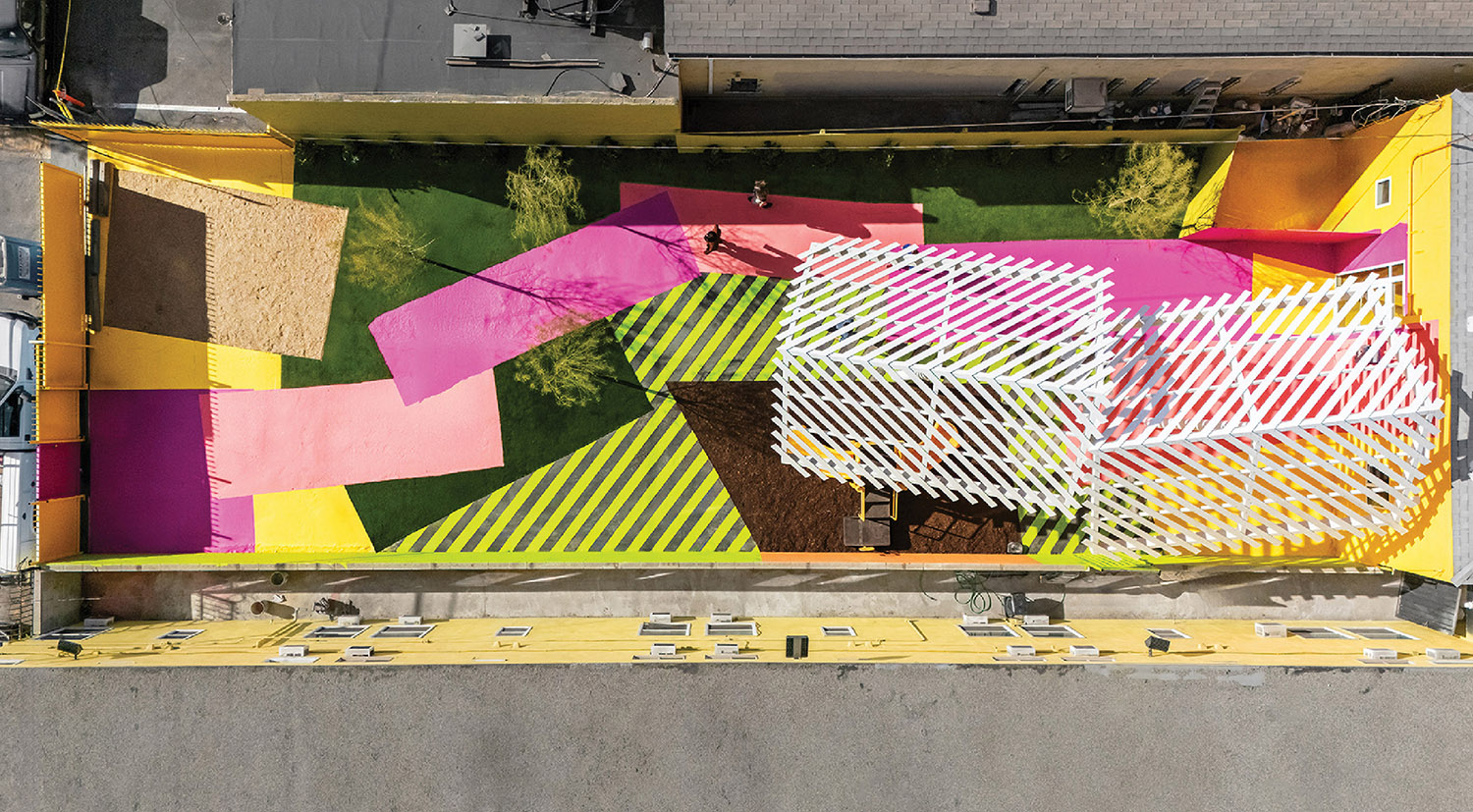

To employ those living with HIV/AIDS, he founded a nonprofit and named it Alpha Workshops for the first letter in the Greek alphabet. (Omega of course being the last.) In 1995, he recalls, “We had $35,000 in the bank from donors.” So he rented space in a light-filled loft building. The studios and a state-accredited training school share one level. Classrooms face the street, while furniture finishing and wallpaper printing have separate dedicated areas. Upstairs are the showroom and offices.

Besides the work done on-site, from gilding to macrame, Alpha sends a crew around the city to Venetian-plaster walls and ceilings. Decorative plastering has, in fact, become the most vigorous business segment. Alpha Workshops licensed product, manufactured by the likes of Koroseal Interior Products Group and Pollack, generates another revenue stream that gets plowed right back into creating good jobs—with health benefits. “When just one architect specifies our vinyls for a Marriott in Oklahoma, that’s $25,000, or two part-time employees,” Wampler notes. With every dollar he earns, more lives are sustained by art.