Memo from Beijing: Insider’s Take

Architect Ma Yansong, a native Beijinger, is known as an important voice in a new generation of Chinese architects. Since the founding of his practice MAD Architects in 2004, his works have been widely published and exhibited. He studied at Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture, holds a degree in architecture from Yale University, and has taught at CAFA. In 2011 he became the first architect from China to receive a RIBA fellowship.

Interior Design: Are you currently working on any projects in Beijing?

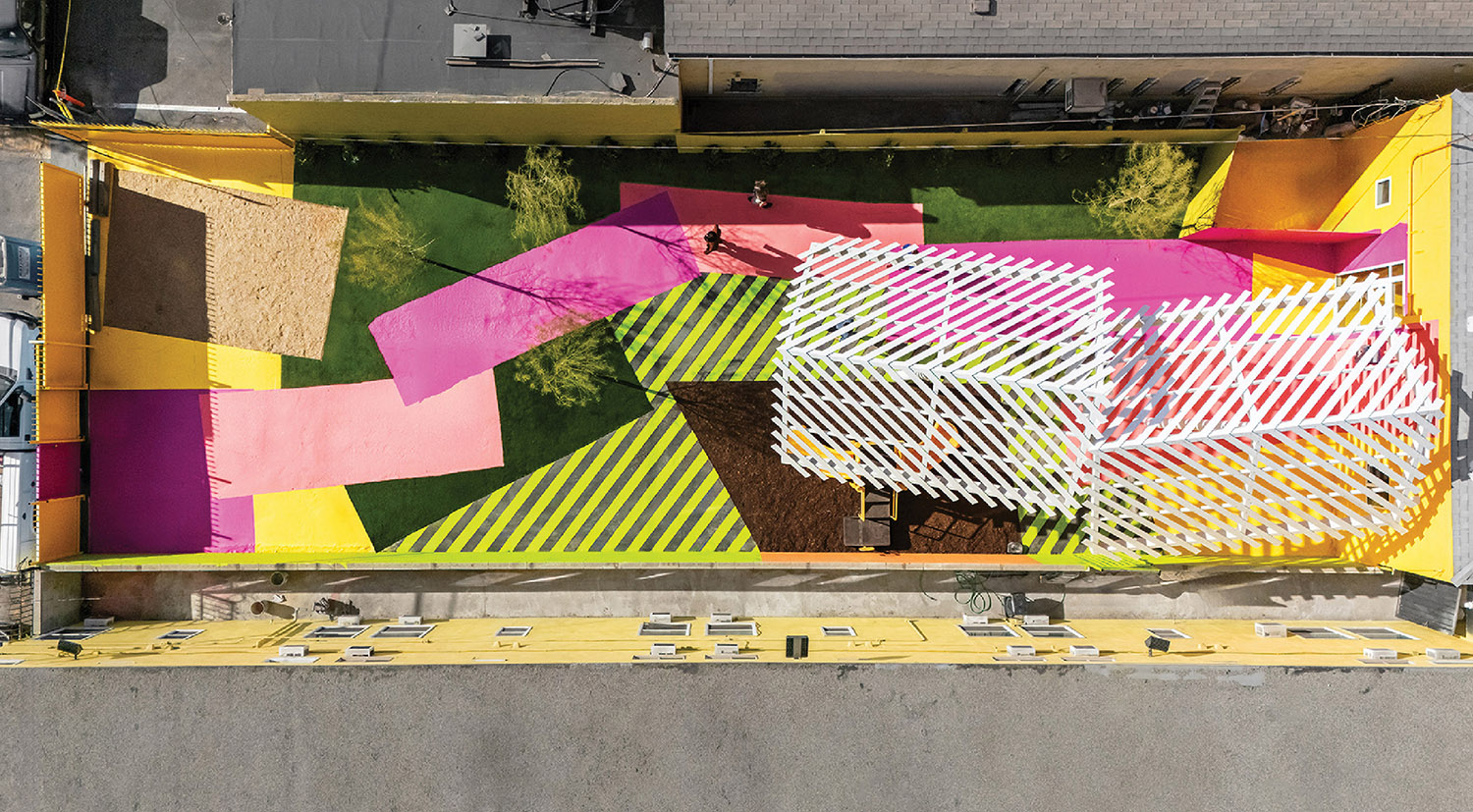

Ma Yansong: Yes. We’re just about to start the planning and designing of a new urban complex near Chaoyang Park. It will consist of commercial, residential and office buildings, inspired by a shan shui vision, literally meaning city of mountain and water. It will combine the urban construction and the natural environment, with two high-rise buildings resembling mountains. The tight integration of architecture-landscape-city is the core of the traditional Chinese city design theory and methodology, and what we strive to follow at MAD too. We’ll also soon be launching a shan shui manifesto, coinciding with an exhibition on futuristic urbanism.

ID: How do you hope it will add to the city?

MY: I hope it will contribute to Beijing’s organic growth as a metropolis, and become an integral part of the landscape, as well as of the community. That’s my vision of urban life—a lot of people integrated with one another.

ID: Is there a specific trait that you think characterizes Beijing’s urban development?

MY: Big buildings and mega cities-inspired urbanism. Which isn’t necessarily a good thing, although it’s perhaps unavoidable at this stage, given Beijing’s rapid expansion.

ID: What drew you to become an architect?

ID: What drew you to become an architect?

MY: As an architect you control lots of resources to build buildings, and those buildings influence society. We build them step by step, and they influence our society little by little. Eventually they become historical trends. This fascinates me, but I’m also aware reaching this level is not very straightforward.

ID: What part of the city is most inspiring to you?

MY: The old hutongs around Houhai. I find the philosophy of traditional Chinese architecture extremely fascinating—how it was so focused on the environment, rather than on visual elements.

ID: With the development of new luxury complexes and rising rents, some say that Beijing is rapidly becoming more commercialized and losing some of the gritty soul that makes it so popular. Do you think this is true?

MY: Sadly yes. Beijing has lost much of its history because of demolition projects that have swept away entire areas. What the city should strive for it’s a new balance within architectural developments and organic surroundings.

ID: An increasing number of international architecture firms are settling in Beijing—and China in general—to work on their own projects. What challenges are they bound to face?

MY: There are a lot of challenges, and these are new for Chinese architects as well as for architects coming from different places. The building boom in China offers so many architectural projects that one might think young architects have it easy. But this is only half-true. Good architecture can capture people’s emotion. Some architects have a lot of opportunities, but that doesn’t mean good architecture. A lot of opportunities also have a lot of traps. They can make you so busy you can lose yourself. You have no time to think.

ID: What does Beijing need more of to grow as a design city?

MY: We need more idealistic or unreal thinking from the people that plan and build this city. Beijing needs a more constructive resolution for the future. I think there are possibilities to make something new yet able to express the feeling of beauty you get with classic architecture. We should work towards that.

ID: Beijing is often compared to Berlin in the 1990s, in terms of reinventing itself as a new city. Do you agree?

MY: In a way. I think there’s this sense that both cities seem to be unendingly works-in-progress. You feel like there’s still room for possibility, and that the place is not fully defined yet.