Raise a Glass: “How Wine Became Modern: Design + Wine 1976 to Now”

The transformation of the winery into an object of serious design began with Clos Pegase in California’s Napa Valley. Completed by Michael Graves & Associates in 1987, this neo-Pompeiian compound gave unprecedented attention to the fusion of landscape, viticulture, architecture, and art. The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art initiated the project—it was the first time that a museum organized a competition for an independent building. The race for the new wine architecture was on.

Staging the encounter of people and wine with brio, the latest crop of distinctive wineries, tasting rooms, wine bars, boutiques, wine-country hotels and spas, labels, glassware, and other objects is the subject of the SFMOMA architecture and design department’s next exhibition. “How Wine Became Modern: Design + Wine 1976 to Now,” on view November 20 through April 17, invites viewers to consider how wine has steadily diffused into popular culture.

Scores of important projects have emerged around the world, including buildings by Mario Botta Architetto, Herzog & de Meuron, Renzo Piano Building Workshop, and Álvaro Siza as well as by the lesser-known but considerable talents of Sebastian Mariscal Studio and Propeller Z. Many of these projects are in California, Spain, and Austria, yet there is hardly a wine-producing country that does not aspire to an expressive architecture of wine. Consider China’s Shanxi province, where the Jade Valley Winery & Resort by MADA S.P.A.M. Architecture combines fragments of an old flour mill with guest quarters organized like a traditional courtyard house.

Steven Holl Architects took a more abstract, even futuristic approach with the Wine & Spa Resort Loisium Hotel in northern Austria. A wonderfully alien folded-aluminum vessel set amid lush greenery, Loisium is linked by a tunnel to a network of wine cellars that date back 900 years, and Steven Holl translated the network’s geometry into the facade’s marks, excisions, and openings. Some of the latter incorporate glass recycled from wine bottles-dappling the bar, shop, and exhibition space inside with delicate shades of green.

The first design winery in the Rioja region of Spain was Santiago Calatrava‘s Bodegas Ysios, an instant landmark that demonstrated the added value of “starchitecture” to the fusion of wine and travel. A few miles away, Gehry Partner‘s Hotel Marqués de Riscal offers a Bilbao-esque tangle of polychrome ribbons that somehow stand for the New Spain. Tradition likewise meets innovation at Zaha Hadid Architect‘s pavilion for Bodegas R. López de Heredia Viña Tondonia. A showcase for a family history of adventurous design patronage, the curvaceous, hypercontemporary structure houses not only a tasting lounge but also, inside it, the elaborately art nouveau mahogany booth that Don Rafael López de Heredia commissioned for the 1910 Exposition Universelle et Internationale in Brussels.

Still another project in Rioja, Bodegas Baigorri by Estudio de Arquitectura Iñaki Aspiazu Iza, articulates a sophisticated approach to the site, the demands of wine production, and the visitor experience. As a glass pavilion rests elegantly atop a mesa, a subterranean interior in raw concrete and steel descends six levels to organize the production sequence with respect to gravity. Alongside, a passageway permits visitors to observe the action as they descend to the stylish restaurant.

A connection to the landscape is key to establishing that coveted sense of place. At California’s Stryker Sonoma Winery, for example, Nielsen:Schuh Architects gave the tasting bar a sweeping view across the vineyard. Experience in California and other New World regions inspired a similar approach at Austria’s Leo Hillinger by Gerner Gerner Plus Architekten. By contrast, Lail Design Group‘s Cade Winery in Napa proposes taking tasting rooms in an inward-looking, intimate direction. Visitors are received in spaces that suggest a private home, with its gracious dining room, living room, and patio.

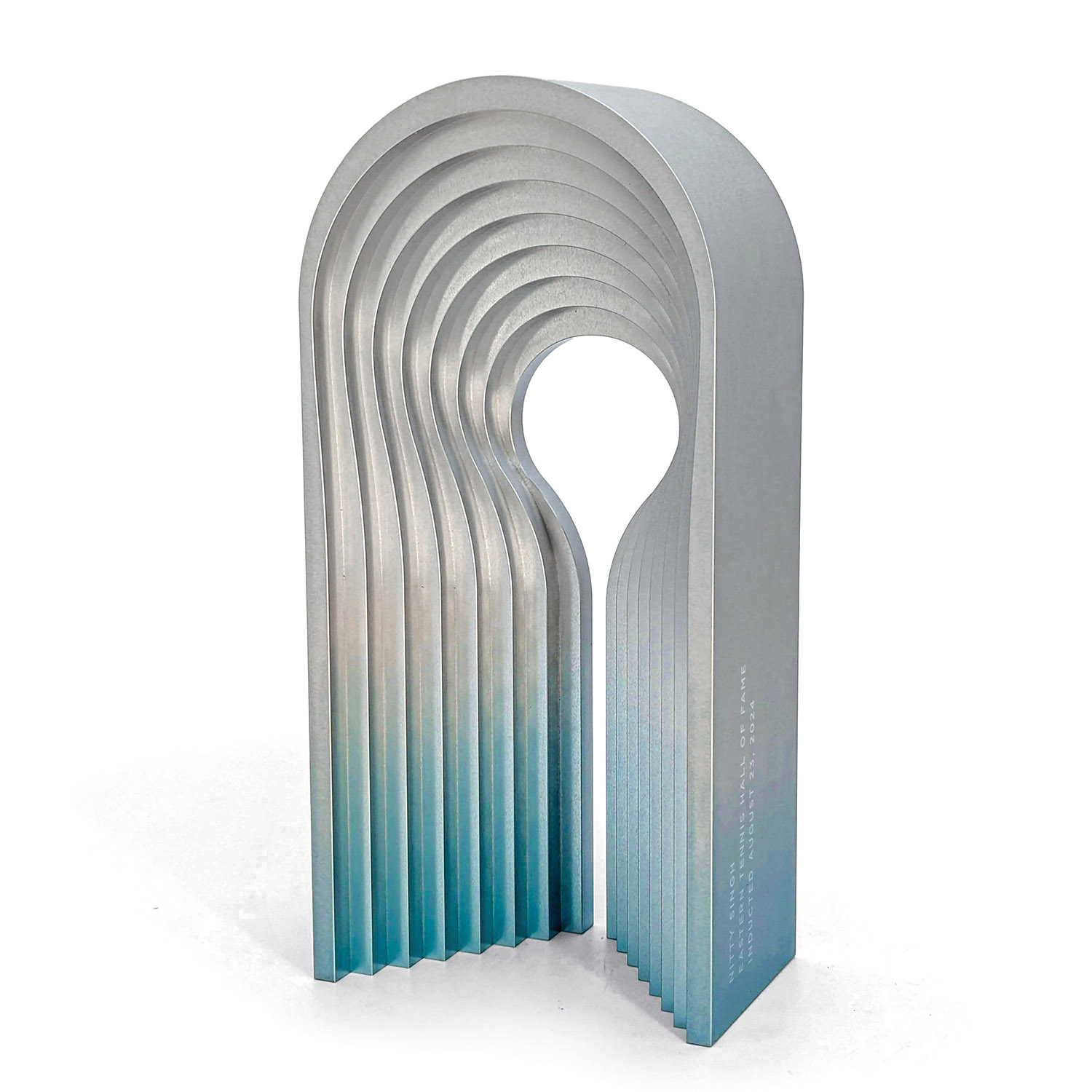

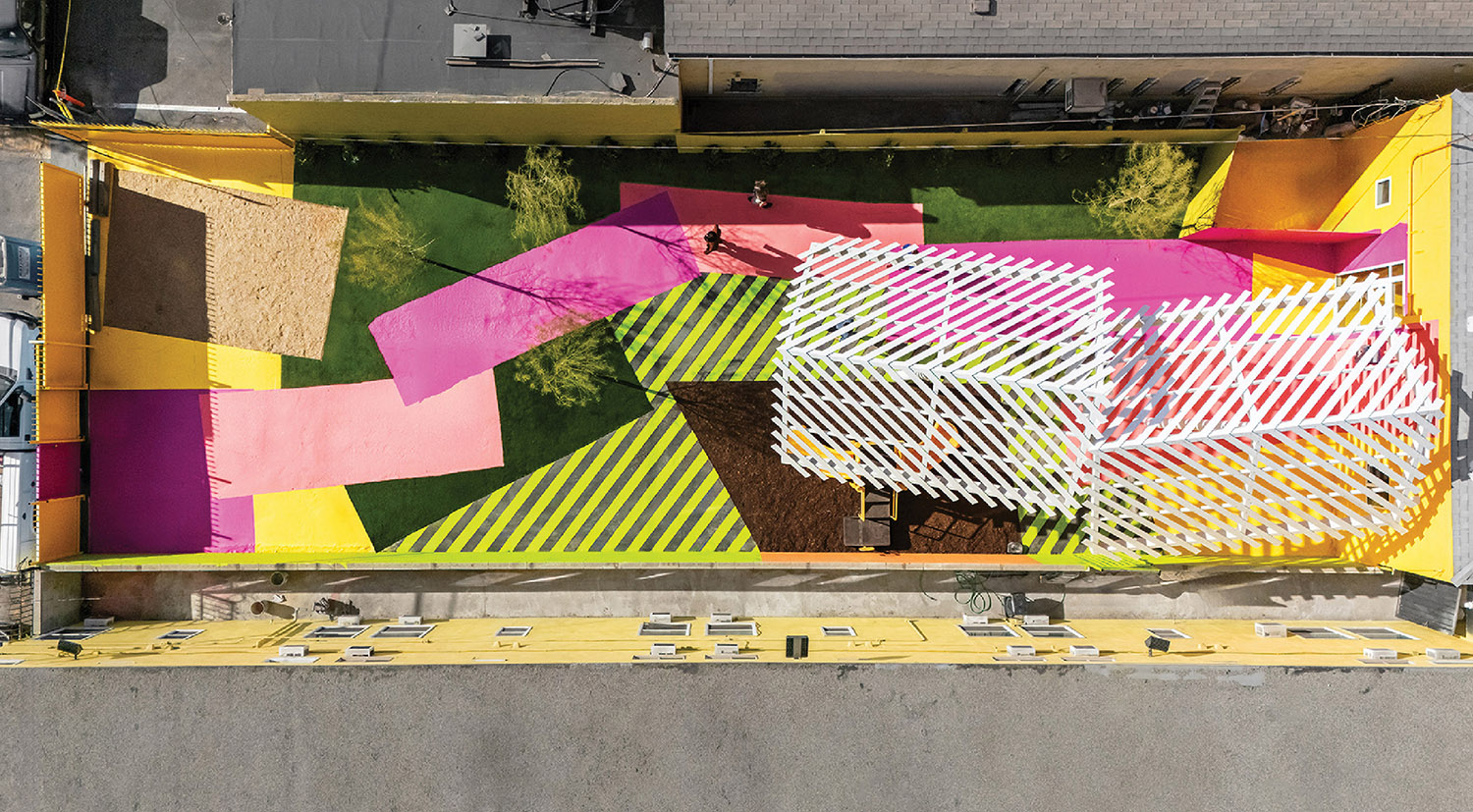

In “How Wine Became Modern,” models and/or photographs of these projects meet artifacts, design objects, and works of art, some newly commissioned, in a sequence that balances immersive, theatrical presentations with individual experiences. One of the great pleasures of attending an exhibition with design as the subject matter is when the designers of the exhibition itself become collaborators in forging a cohesive environment from content and form. That’s precisely what Diller Scofidio + Renfro accomplished here, and the result is, as expected, exhilarating.

Gallery conditions that conventional strategies could miss are maximized. Taking advantage of the 18-foot ceiling, red wine slowly drips from overhead into a vitrine displaying glassware. And a strangely hidden nook shows such secretive aspects of modern production as the additive Mega Purple, surreptitiously used to darken wine.

While making note of excellence, of course, the exhibition is a deconstructive project. It gathers these many objects to argue for the coherence, however nuanced, of wine-driven design and to invite viewers to look afresh, not uncritically, at wine and the culture that venerates it so.