Residential and Dental Meet in ARSP’s Mixed-Use Building

A six hours’ drive west of Vienna, in the lakeside village of Hard, with its 12,000 inhabitants and little in the way of progressive architecture, Michaela and Robert Immler had a clear idea about what their home and dental practice should look like. Their meticulous outline of 20 must-haves, presented to ARSP Architekten Rüf Stasi Partner, included white walls, wooden floors, and wooden furniture, adding up to a detailed picture of the couple’s imagined lifestyle. What didn’t they envision? A triangular structure. Or pretty much anything else they ended up receiving. “When they moved in, they found their wish list again and realized they had only three of its absolute must-haves fulfilled,” Frank Stasi says. “They had asked for all these standard things. We don’t do standard.”

Stasi and Albert Rüf, eager to create something new and different, instead designed an “intelligent, low-cost building” with an aesthetic that was “really simple and pure,” as Rüf describes it. Even before they presented their three-sided floor plan, they waged a campaign to persuade the Immlers to swap out their preferred drywall and wood for a spare, loftlike scheme incorporating polished concrete floors paired with walls in raw concrete and occasionally bare brick. “We had to get through to them that unplastered walls could be really beautiful,” Stasi adds, citing as inspiration the current Austrian and German vogue for reclaiming and sleek-ifying old factories.

>> See the project’s resources here

Definitely nonstandard is the three-story, 6,000-square-foot building’s unconventional shape: a right triangle with a slight outward angle in the hypotenuse, fronting the street, and asymmetrical windows that further make the facade stand out amid standard-issue storefronts. Beyond mere irreverence, each of those attributes serves a specific purpose in ARSP’s scheme. For example, the subtle bump-out in the facade’s 100-foot-wide white expanse produces a kind of optical illusion. “Because of that tiny kink, the light changes from one side of the elevation to the other, so your perception from the street is that the building isn’t quite as wide,” Stasi explains. “That helps keep it at a more human scale to fit in with its surroundings.”

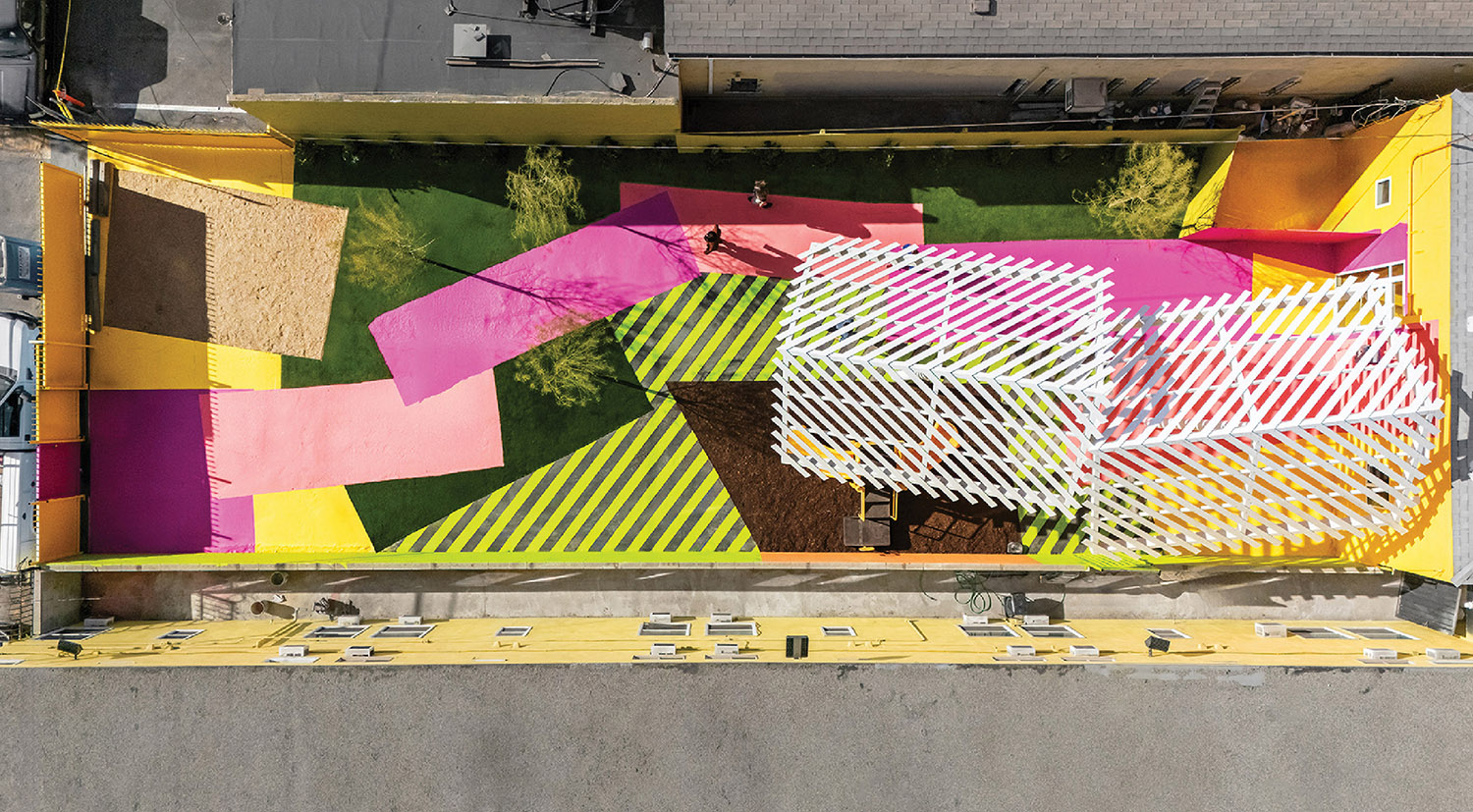

One of those few requests from the Immlers that ARSP honored was for a back garden, which would have proved difficult on such a small plot of land had the architects opted for a more traditional footprint. With two angled rear walls, the building pulls away from close-set neighbors on both sides, creating more room for the garden while ensuring it ample sun exposure. ARSP further maximized the functionality of the resulting void by cantilevering massive balconies into it. There’s a balcony for one of the pair of rental units on the middle level, plus two balconies for the Immlers’ own apartment at the top.

Nowhere do the building’s quirks feel more purposeful than in the Immlers’ home. Reaching it requires climbing a staircase with a blackened-steel balustrade, its irregularly spaced bars meant to mimic tree branches moving in the wind. The stair terminates in the center of the open-plan public space, beneath the 23-foot-high apex of a pyramidal roof that rises from the three exterior walls. It was achieved in one fell swoop of poured concrete that took a skilled contractor 18 hours to execute. “You’d normally build this kind of roof out of wood, but the rafters would have interrupted the space,” Stasi explains. “What we did is more cathedral than living room.”

He and Rüf also chose the concrete for the roof as part of their concept of uniform materials. Nearly every surface in the apartment is concrete. In fact, the reason the master bathroom’s sink vanity is freestanding is because mounting it to the wall would have required covering the concrete in drywall, disrupting the purity of the scheme. The few exceptions include the ash-veneered plywood for the bathroom’s doorways and closet doors and, in the adjacent bedroom, a wall of exposed brick. (New internal insulation technology keeps heating costs down.)

Exposed brick didn’t meet hygiene standards for the ground level’s dental office, which otherwise embodies the architects’ vision from upstairs. So the envelope is essentially all-concrete—softened very slightly, in the waiting room, by the chartreuse wool felt used for upholstery, drapery, and a curved partition. As Stasi jokes, “It’s not supposed to be comfortable to go to the dentist. It hurts!”

Project Team :

Nicholas Thiele; Matthias Duffner: ARSP Architekten Rüf Stasi Partner. ProfiMed: Dental Consultant. Mader & Flatz Ziviltechniker: Structural Engineer. 3P Geotechnik: Civil Engineer. Bartosek: MEP. Farben Krista: Plasterwork. Peter Figer Kunstschmiede: Metalwork. Kaufmann Zimmerei Und Tischlerei; Sternath Tischlerei: Woodwork. Oberhauser & Schedler Bau: Concrete Contractor.