Steps in the Right Direction: UnSangDong Architects Beautifies Waste Disposal

Mention the term wastewater treatment plant, and most people will either draw a visual blank or picture a drab cube, its primary purpose being to hide what society would rather forget exists. Not so in the South Korean village of Songsan, home to the headquarters of Sun Myung Moon’s controversial Unification Church. No matter what you think of the Moonies, their initiative to turn raw sewage into an opportunity for ecological education and contemplation is unquestionably innovative. “Sewage treatment facilities generally focus on function without consideration for the environment or aesthetics,” UnSangDong Architects Cooperation principal Yoon Gyoo Jang says. The firm handled every aspect of Cheongshim Water Story, from the exterior and interior architecture to furniture and exhibition planning.

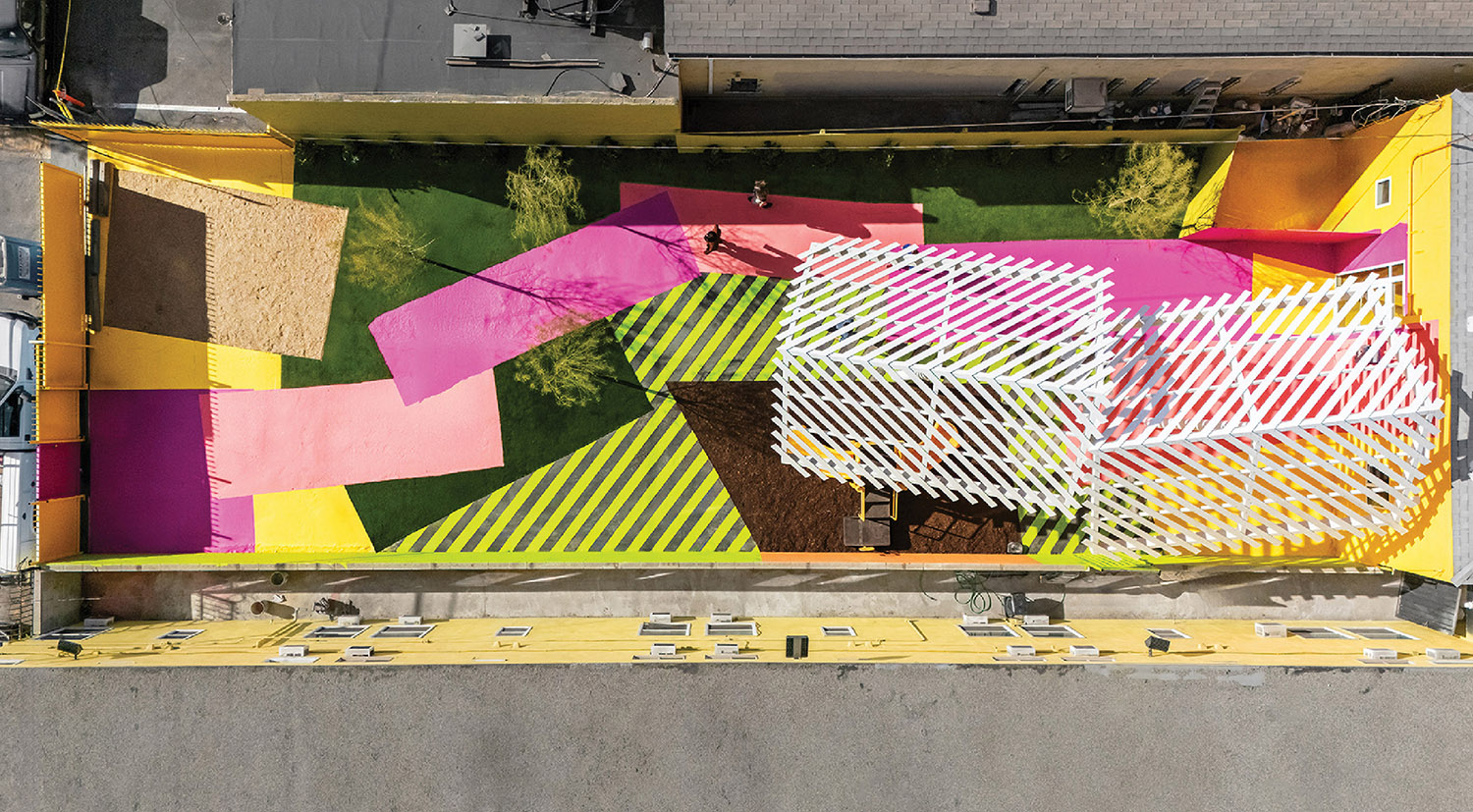

Before the facility went into operation, sewage from church-run schools, hospitals, etc., used to flow to a treatment plant in a wooded valley, then cycled back to the village for reuse. But as development continued, capacity ran out. So UnSangDong, which had completed several projects for the church, returned to design a plant that would share a location with an educational center. A 36-foot-high concrete cylinder of a building, standing out against the trees and fields, it draws visitors to a remote area and proudly heralds the plant buried below.

The educational center is part conceptual tribute to water, part museum, and part hands-on classroom where visitors, mostly kids on school outings, learn about the importance of clean water. UnSangDong conveys that message in myriad ways—beginning with the shape of the structure. “We see the circle as the archetype of geometry. It relates to many of water’s characteristics, such as the ripples that radiate from a drop of water in a pool and the pureness of water as the essence of life,” principal Hoon Shin Chang says.

For reasons that have less to do with symbolism than conservation, the exterior of the cylinder is nearly unbroken by windows. Solid concrete helps stabilize interior temperatures, which is important for maintaining the machinery that runs around the clock in the underground plant. Light shelves and ducts bring in a certain amount of sunshine, and the galleries and classrooms can be fully lit when visitors arrive—given the location, they’re not a steady stream. Energy savings, related to heating and cooling, therefore more than offset the expense of extra artificial lighting.

Topping this perfect cylinder, the roof deck is carved out in three sections. Two descend just partway, to a lower deck, with amphitheater seating for outdoor classes lining the descent. The third and largest, which is fenced off, steps steeply down to a void over the front entry. To UnSangDong, these excavations represent the contour lines of an imagined topography. “It’s a metaphor for the mother earth that bears water,” Jang explains.

Inside the cylinder, a 7,200-square-foot space with the void subtracted, the emphasis is on encountering water in all its shape-shifting manifestations. The young—and the young at heart—are handed raincoats before heading to splash in a pool filled by the “rain” that falls from part of the lobby ceiling. From there, visitors can walk up to an interactive media wall that creates the illusion of their reflections underwater, with bubbles and ripples responding to movement, or take a stroll through the “fog box,” a glassed-in garden where a path meanders between moss and other dampness-loving plants. Hovering in the atrium that unifies the first and second levels, a huge aquarium contains live carp. Water for the rain, the fog, and the fish is, of course, all treated on-site.

“Experiencing various forms of water makes people realize its importance more effectively than watching documentaries or listening to lectures. That’s especially true for children,” Chang says. But the wizardry required technical dexterity. To cycle water from the treatment plant into the exhibits, UnSangDong had to conceal a complicated network of pipe behind the white walls. To protect them from the constant moisture, they’re coated with mold-beating, antibacterial agents and acrylic paint usually reserved for outdoor use.

Lessons are more conventional in the classrooms and laboratory. Entirely unconventional, guided tours through the bowels of the building allow visitors to observe the purification equipment itself. Rendering the treatment plant visitor-friendly was actually fairly straightforward. Although up to 5,500 tons of sewage pass through daily, it stays inside the tanks and pipes, so smells, sounds, and disease don’t pose a problem. Small windows in the tops of the tanks provide a glimpse of what happens inside. To make the industrial aesthetic more welcoming, pipes and beams are painted bright colors, and the main circulation route passes between stands of dried reeds.

“As society continues to urbanize, we have to rethink our attitude toward waste disposal and learn how to live with these facilities in our backyards,” Chang says. That’s a goal well worth the investment: at Water Story, the equivalent of $16 million.

Project Team: Mi Jung Kim (Project Architect); Kyung Tae Kim; Samuel Ryu; Jae Hyun Shim; Bong Kyun Kim: Unsangdong Architects Cooperation. Elpis Design: Lighting Consultant. Design Tomorrow: Graphics Consultant. Kujo: Structural Engineer. Yoolhyun Engineering: Civil Engineer. Hanil Mec: MEP. Han Glass: Glasswork. Yoolim Timber: Woodwork. Hyomyeong E&C: Concrete Contractor.