Stop the Presses: Bak Gordon Builds Giant Olive-Oil Factory

It appears from nowhere. As you drive across the sun-baked brown flatlands of Portugal’s Alentejo region, a monolith suddenly materializes on the horizon, like a long, slim spaceship hovering above low groves of olive trees near the town of Ferreira do Alentejo. And the bold appearance of the building matches its importance. At 60,000 square feet, the factory where Sovena produces its Oliveira da Serra brand of olive oil is the biggest in the nation.

Bak Gordon Architects‘s design comprises two visual components: an oblong charcoal-gray base and a vaguely trapezoidal white volume cantilevered on top. Because the base is not only smaller and darker but also slightly below grade, the superstructure appears to be “a pure shape touching down on the landscape or growing from the ground,” Ricardo Bak Gordon says. To increase the effect, he ensured that the olive groves ringed the factory as closely as possible.

Because both the first and the final phases of olive-oil production take place outdoors—unloading the trucks delivering raw olives and filling the tanker trucks with oil bound for the bottling plant—Bak Gordon extended the white superstructure longer than the gray base. This creates an overhang at each end of the building to shelter workers against the rain of fall and the extreme heat of summer, sometimes nearly 120 degrees Fahrenheit. “When you’re filling the tanks in September, shadows are very important,” he says. The exterior design also takes into account olive oil’s unusually short and intense production schedule, round-the-clock for four months in the late summer and fall. To illuminate the two outdoor work areas at night, the undersides of the overhangs are essentially two huge light boxes, with incandescent lamps shining through surfaces of translucent polycarbonate.

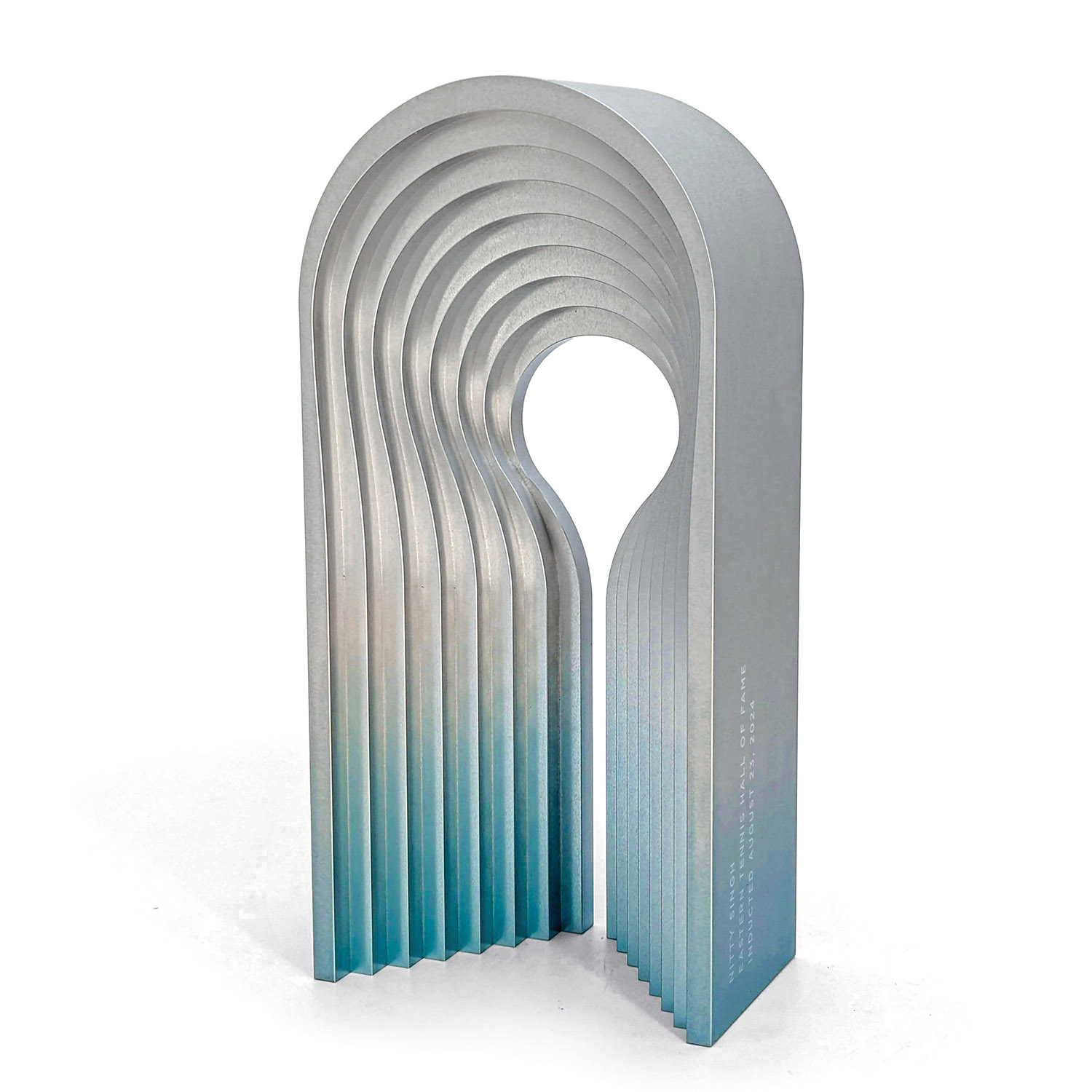

To make the factory accessible to school groups, academics, media representatives, and other special guests, Bak Gordon installed a separate visitor’s doorway—and signaled its presence by carving a huge oval out of the facade directly above. The rounded aperture, an exaggerated horizontal version of an airplane window, plays against the “rigid geometry” overall, he notes. So does the staircase inside, a white form that spirals sinuously upward in the dimly lit, otherwise empty atrium. “You’ve come from the outside, which is hot and bright, and the entrance is very dramatic,” he explains. “The colors are quite cool and the light quite controlled. It immediately gives you the impression of power.”

The entry is part of a transverse enclosure, two stories flanked by the double-height production and storage areas. At the top of the stairs, the tasting room indoctrinates visitors with facts related to olive oil production. (Did you know that an eco-friendly factory, such as this one, can crush and burn the leftover pits to generate power?) On the consumption side, the tasting room’s open kitchen allows guest chefs to give workshops on cooking with the product. Long, slim skylights make the gallerylike space suitable for art exhibitions, as window walls on both sides offer an overview of activity on the factory floor, where machines press and centrifuge the fruit, then filter the oil.

Beyond the tasting room, the window walls extend into a conference room. At the far end is an administrative office. The enclosure’s lower level, meanwhile, houses a laboratory that test the properties of each batch of oil, ensuring that it’s ready. Flooring in the lab is green, as are the floor and the occasional wall in other areas involved in either production or storage-but not a realistic olive green. Bak Gordon amped up the intensity of the shade, making it more vivid, more electric, more fun.

Similarly, the polycarbonate of the overhangs’ light boxes is tinted the golden color of olive oil. When the factory lights up at night, the glow can be seen from miles around by the multiple farmers who grow and sell the olives used to make 2 million gallons of Oliveira da Serra oil per year. Bak Gordon hopes that this very contemporary beacon will serve as an inspiration to a regionthat has been economically depressed for years. It’s a positive example that says, “We’re back.”

PROJECT TEAM

Luís Pedro Pinto; Nuno Velhinho; Pedro Serrazina; Sónia Silva; Vera Higino; Walter Perdigão: Bak Gordon Architects. Iradu: Civil, Structural Engineer, MEP.