Teach Your Children Well: Toronto’s Native Child and Family Life Centre

The official name of Toronto’s east side is Scarborough. Unofficially, it’s called Scarberia—an appropriate description for bleak strip malls, rundown mid-century apartment towers, and little else. That’s the scene found by Dean Goodman at the intersection where Levitt Goodman Architects was asked to build the Native Child and Family Life Centre.

Levitt Goodman had already renovated a headquarters building for Native Child and Family Services of Toronto and constructed a dining lodge for a summer camp operated by the nonprofit, which provides day care, addiction counseling, emergency housing, and more for the city’s substantial native population, known in Canada as the First Nations. The Scarborough project, however, presented significantly different obstacles. First, Goodman and associate Danny Bartman had to incorporate a Victorian farmhouse, protected by a historical designation. Next, they had to abide by Ontario safety standards for interiors dedicated to infants, toddlers, and preschoolers. Finally, the toughest challenge: fulfilling very big ambitions on a very small budget, the?equivalent of $4 million in the U.S. “This particular First Nations community doesn’t have the financial resources of other institutional clients,” Goodman says. “But they knew that a bold statement would help revitalize the neighborhood.”

“Bold statement” certainly describes the Levitt Goodman component. On the street facade of the main structure, an irregular composition of windows intercuts Cor-Ten steel cladding in vertical strips. The oxidized metal complements the red brick of the farmhouse, and the old and new are connected physically by an entry with an elegant canopy. Together, the addition totals 10,000 square feet—that doesn’t count the farmhouse, previously converted into offices.

The main structure’s tapered shape evokes a Haudenosaunee longhouse, a motif that reappears inside. Reception, offices for administrators, and day care for infants and toddlers are on the ground level. The upper level, reached via stairs covered in purple rubber, is home to preschool-age playrooms and a community meeting room with a full kitchen. The vaulted ceiling creates drama, at over 15 feet. So do the trusses and purlins. In another nod to First Nations building, their intersecting angles recall how saplings would have been strapped together for roof support.

In the playrooms, tall windows give kids a street view and a sunny place to curl up at nap time. Walls between the exposed studs are durable spray-sealed plywood, which the children are encouraged to personalize with drawings and photos. “The more the kids make the space their own, the better,” Bartman says.

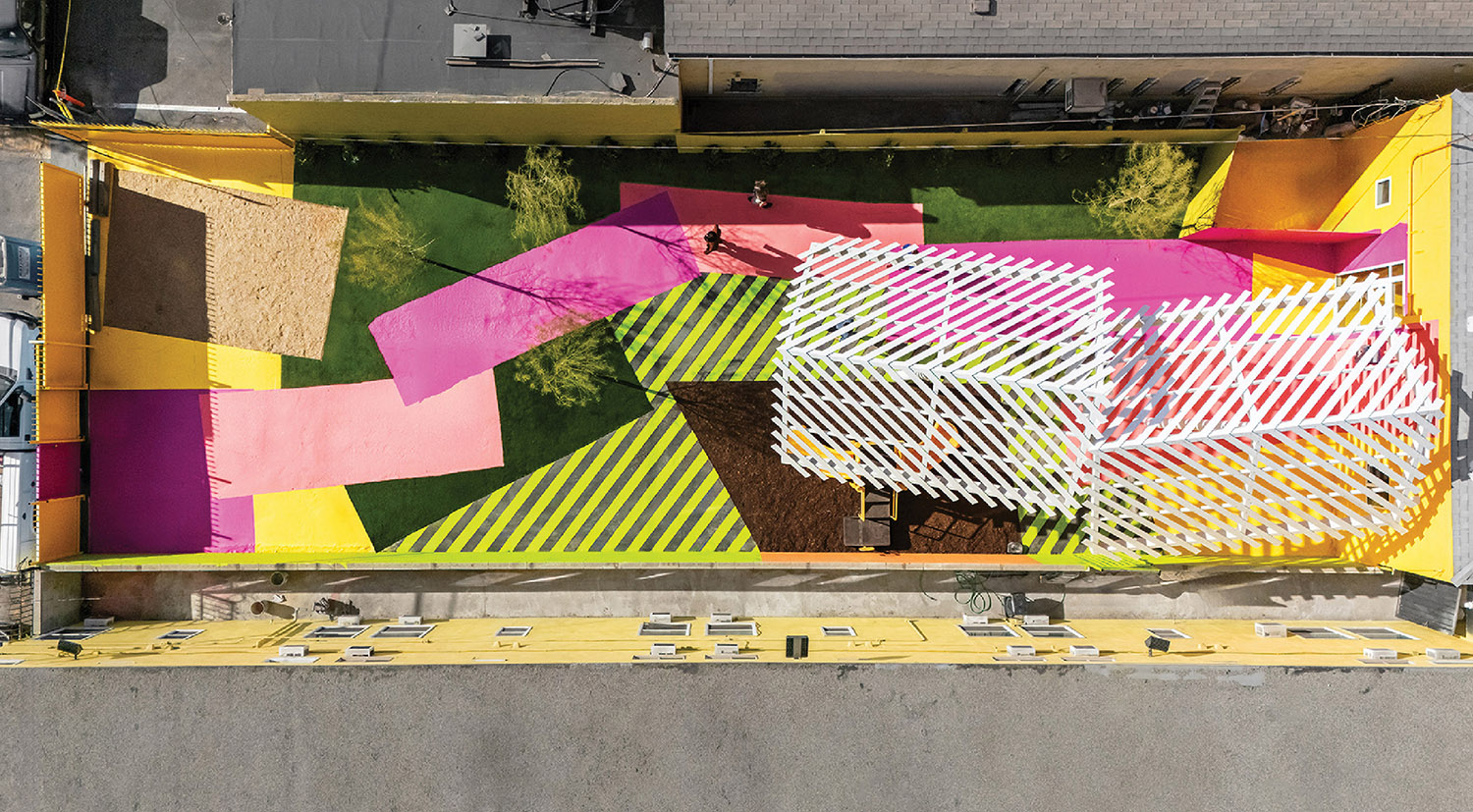

Since part of the brief was to design a playground, Goodman and Bartman placed it behind the building, screened from the busy intersection. In addition, they persuaded their client to forego concrete pavement and plastic jungle gyms in favor of grass, rocks, logs for balancing games, and a long path for zipping back and forth on tricycles. For creative scribbling, a storage shed’s painted doors do double duty as chalkboards. The playground is bisected by a gravel-filled ditch that, after a rain, becomes a shallow stream for splashing, and the area alongside is designated for picnic lunches. Community members even have enough space to erect a ceremonial sweat lodge on special occasions.

The center has quickly become a Scarborough landmark. Day care is at capacity, and the community room hosts an uninterrupted schedule of coffee meetings and potlucks. The center furthermore offers proof that-with an inventive overall vision and careful attention to detail-locally available Eastern white cedar siding, basic plywood, factory-made structural components, and standard hardware can produce something artful and distinctive yet cost-effective. Every hard-luck neighborhood can benefit from that lesson.

Images courtesy of Ben Rahn/A-Frame.