Zurich’s Pavillon Le Corbusier Serves As A Monument to A Pioneer of Modern Architecture

Nearing his eighth decade of life, Le Corbusier had long ago abandoned his Swiss hometown, La Chaux-de-Fonds, along with his birth name, Charles-Edouard Jeanneret-Gris, to spread his radical vision and establish himself as the planet’s pioneer of modernism. His apartment and office were in Paris, not far from the futuristic villas that had launched his global fame. His portfolio of revolutionary structures in raw concrete extended from the Cité Radieuse housing complex in Marseille to Harvard University’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts and a massive government district in Chandigarh, India. Switzerland, which he regarded as provincial and insufficiently appreciative of his talents, was a far-off memory.

Then a Zurich art dealer, Heidi Weber, fell in love with his artistic creations—paintings, sculpture—in addition to his furniture and tracked down the aging architect at his French Riviera vacation cabin, the famous Cabanon. She first persuaded him to sell his works at her gallery, Mezzanin. Soon, she was urging him to return to Switzerland to build an entirely new structure to house his oeuvre for future generations. It would be a temple to the one thing he admired most: himself. Le Corbusier accepted the challenge.

“I am 73 years old, and this is the first time that country has shown me the slightest courtesy. What a surprise!” he wrote to the French cultural minister, author André Malraux, in 1960. He wrote to another friend, “This house will be the most audacious of my entire career.”

Weber and Le Corbusier envisioned an idealized “house and studio,” actually uninhabited, that would show off his talent, both architectural and artistic, to the public. They broke ground in 1964. Today, the structure is officially named the Pavillon Le Corbusier and is run by the city of Zurich as a museum, open in the summer only. As the ultimate expression of Le Corbusier’s distinctive genius at the final stage of his evolution, the site is ripe for a revisit.

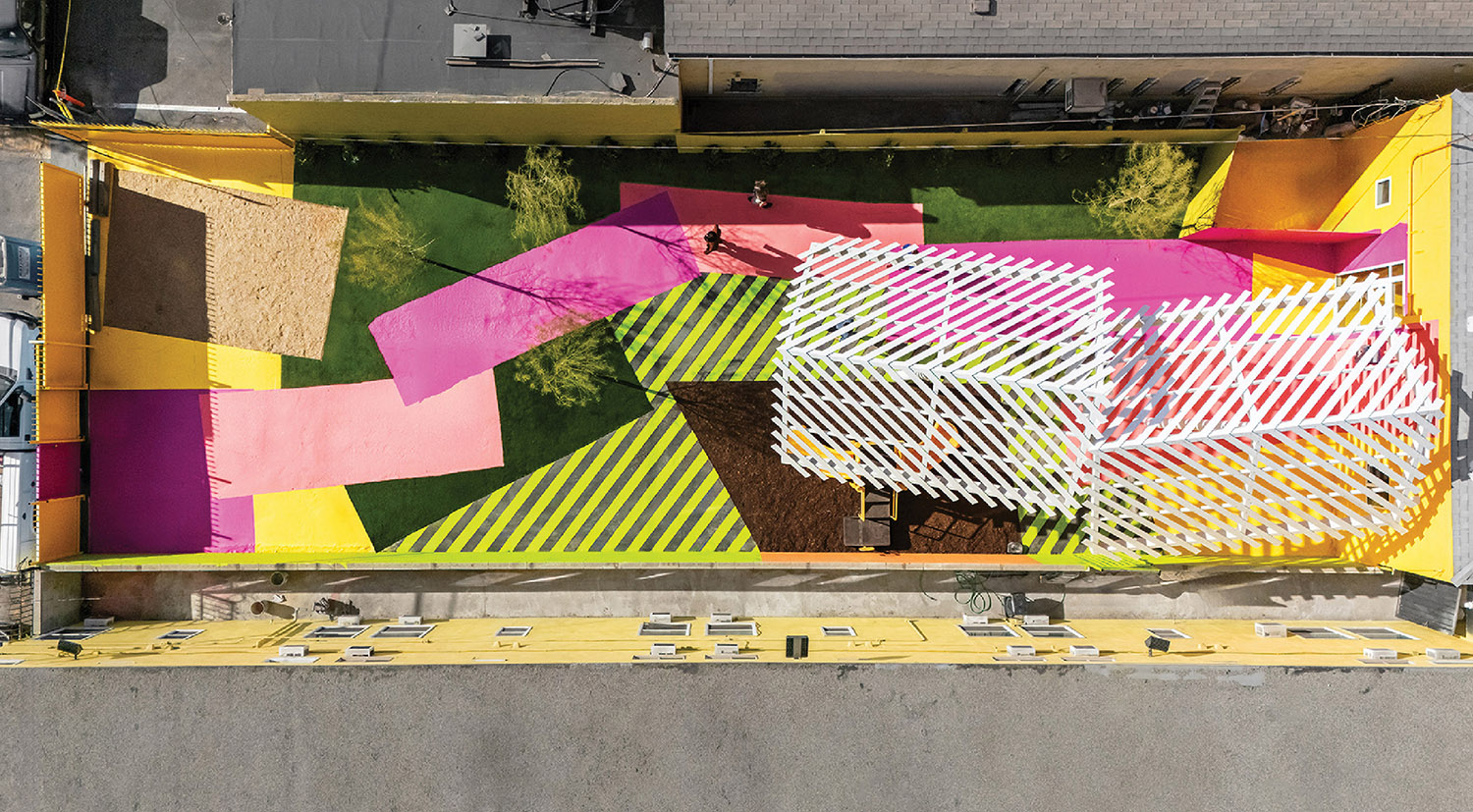

The colorful modernist pavilion bursts kaleidoscopically from its leafy Old World surroundings, populated by traditional houses and neo-Gothic mansions. At once recognizably Corbusian yet impressively innovative, the facade’s panels enameled in solid colors—red, yellow, green, white—stand out like the pieces of a Rubik’s Cube. Uncharacteristically, though, the base of the structure is flush with the ground: There are none of his characteristic pilotis, the load-bearing columns he used to raise buildings. Equally unusual: There is very little visible concrete. In place of the solidity and power of iconic Le Corbusier edifices, the two-story, 5,000-square-foot pavilion appears light, delicate, and transparent, perhaps due to the influence of Jean Prouvé, who consulted on the project. The most eye-catching feature is the steel canopy, an origamilike umbrella that floats over the building proper on thin posts.

Steel and glass dominate the design, which Le Corbusier described as a “marriage of nature and geometry.” Everything is built around an exposed three-dimensional grid of columns and beams placed at intervals of about 7 ½ feet. (This measurement, corresponding to the height of an average man with his arm raised, represented Le Corbusier’s ideal basic dimension for human habitation, a scale that he called the Modulor.) Industrial materials and geometric motifs appear everywhere from the oval doors, inspired by those on ocean liners, to the rows of raised circles on the black rubber flooring in certain places. Exposed mechanicals contribute to the factory feel—only painted in symbolic colors: blue for water pipes, red for heating ducts, yellow for electrical conduits. Clearly, the “machine for living” remained a guiding metaphor for Le Corbusier until the very end.

As for the “nature” part of the equation, it’s evident in such details as the canopy’s triangular aperture, which gives a direct view of the sky to anyone sitting below on the roof terrace. The moving sun casts angular shadows through this cutout, while a purpose-built pond behind the building reflects sunlight upward, projecting a glow on the underside of the canopy to complete the luminous interplay. Bringing nature indoors and simultaneously bearing witness to Le Corbusier’s love of simple repeating forms, natural materials include oak for square wall panels and granite for rectangular floor slabs. Thanks to the glass curtain wall, the lake and forested hills of Zurich meet you at every turn. In addition, slim glass panels are operable windows that swing open to admit air from outside. Flooded with sunlight, the rooms both embody and showcase Le Corbusier’s diverse output, from early versions of his iconic club chairs and chaise longues to abstract paintings and sculptures.

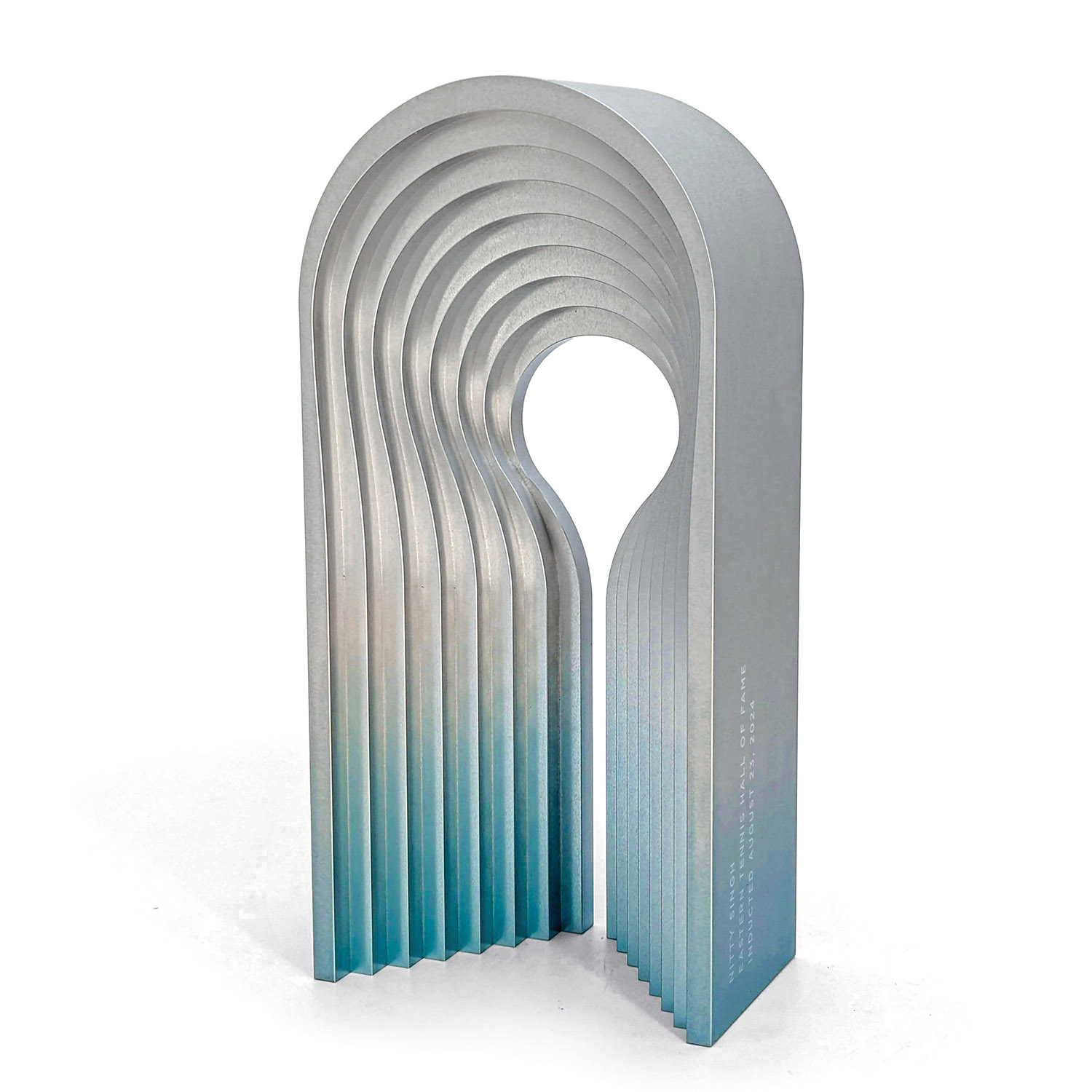

Alas, the building’s creator didn’t live to see its completion. While staying at his Riviera refuge, he drowned in 1965, a year after construction on the pavilion began. It was inaugurated two years later. Now approaching its 50th birthday, the design stands as a revolutionary, ever innovative modernist’s final testament, his homecoming, and the sum of all of his parts—architect, furniture designer, artist, theorist, author—all held together with 22,000 bolts.

Throughout: PRF Group: Rubber Flooring.